Executive Summary

This paper is the second of a series proposing the creation of an urban-focused guarantee fund, the Green Cities Guarantee Fund (GCGF) to derisk lending and attract capital in support of climate resilient infrastructure in cities in the Global South. Paper one, “The Green Cities Guarantee Fund: Unlocking Access to Urban Climate Finance” provides an overview of current practices and impacts in the realm of guarantees, and proposes the creation of an urban-focused guarantee fund, the Green Cities Guarantee Fund (GCGF) to derisk lending and attract capital in support of climate resilient infrastructure in cities in the Global South. It outlines the steps to implement the GCGF, highlighting the structural and operational details to be developed as guided by general principles covering governance, structure, and operations, eligibility, and climate impact.

This paper details the rationale for highlighting the seven countries as likely candidates for piloting the GCGF [1]. Part 1, Regional Context Supportive of Guarantees, briefly outlines two long-standing Latin American transformations, rapid urbanization dating from the 1950s and transitions to democracy in the 1980s, and describes four qualifying characteristics that indicate a country’s readiness to roll out and support subnational finance. Part 2, Pilot Country Profiles, provides detailed analysis of the seven countries, assessing their alignment with four qualifying characteristics: 1) the level and quality of its decentralization, 2) an appropriate regulatory framework, including the enabling environment for public private partnerships, 3) the level of maturity of its local financial market, and 4) its subnational risk profile. Part 3, Next Steps for Piloting Guarantees in Latin America, summarizes the case for implementing the proposed Green Cities Guarantee Fund in this region.

Part 1. Regional Context Supportive of Guarantees

Understanding of recent history and development in the seven countries is essential for discussions related to finance for subnational governments’ development and climate change projects. Two transformative trends, the rise of urban populations and transitions to democracy have created the special investment climate in which guarantees would be useful.

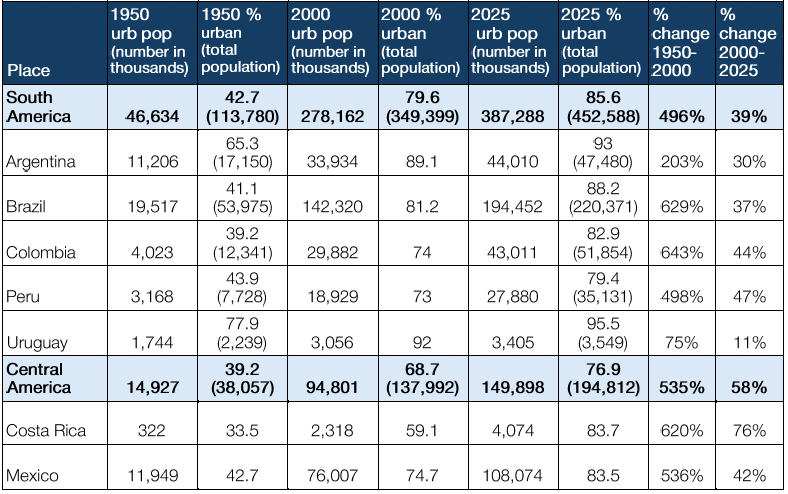

1.1. The implications of 20th and 21st century urbanization

The seven countries experienced dramatic rates of urban growth in the last half of the 20th century, a phenomenon that created more than 300 million city dwellers in South America (up from 47 million in 1950) and more than 100 million in Central America (up from 15 million five decades earlier). While urban growth rates slowed in the 21st century, it took only 25 years for the number of urbanites to increase by more than 50 percent to more than half a billion (91 percent of the total population) of the combined South and Central American population. See Table 1.

Table 1. Urban Growth in Selected South and Central American Countries

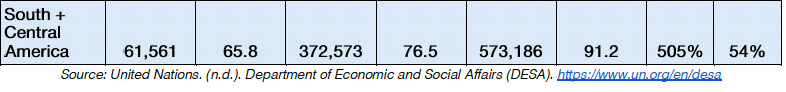

By 2025, several megacities emerged: São Paulo (23 million), Mexico City (23 million), Buenos Aires (16 million), Rio de Janeiro (14 million), Bogota (12 million), Lima (12 million), followed by more than 42 cities with populations exceeding a million, 52 with populations 500,000-999,000 and some 30-50 in the 250,000-499,000 range [2]. Overall, the region has many smaller municipalities. The OECD reports South America with more than 11,000 cities and Central America, 2,600 cities. OECD’s records of the average size of the municipalities in each country range between 20,000 to 60,000 [3].

In the selected countries, the number of municipalities ranges from 82 to more than 5,000. While Mexico and Brazil stand out in the region for having high numbers of municipalities, Peru, Argentina, and Uruguay actually have a larger number relative to their total populations. In terms of average size, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Colombia’s municipalities are approximately double the size of those in the other countries. See Table 2.

Table 2. Subnational Governments and Municipalities to Total Population Ratio

These data indicate the complex nature of servicing cities with relatively small populations that likely lack management capacity and whose projects are too small to attract large public and private sector investors. This situation calls for approaches that either focus on the larger cities or that aggregate smaller city projects into portfolios that can attract investors.

Moreover, the rate of urban growth in these places has exceeded the public sector’s ability to provide developable land for housing and associated basic services. This phenomenon has had important spatial impacts on cities, their surroundings, and collectively on their ability to provide and finance infrastructure. As a result, informal (squatter or slum) settlements cropped up on interstitial land within cities and sprawled at their peripheries. Variously named, villas miserias in Argentina, favelas in Brazil, ciudades perdidas in Mexico, they were originally unserviced and lacked tenure or even addresses. Over time, residents upgraded their dwellings transforming them from fragile wooden shacks to buildings of brick and concrete.

Eventually city governments began to supply water, sanitation, and paved streets in a process labeled “consolidation” and slums as a percentage of urban housing declined [4].

Nonetheless, in 2022, the latest date for available data, slum conditions still account for approximately 17 percent of urban housing in the region. In Peru they constitute 45 percent of the urban housing, and slightly under 20 percent in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico [5]. Due to their disorganized layouts on often environmentally vulnerable land, inadequate transportation infrastructure, and deficiencies in sewage and electricity, most of these settlements need large investments in resilience-oriented infrastructure [6]. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Slums as a Percentage of Urban Housing in the Seven Countries 2022

1.2. Rise of middle-Income populations

In the first decade of the 21st century, the emergence of a significant middle-income group accompanied the growth of cities. In 2019, economists reported that about a third of the region’s population was middle income (defined as earning between USD 10 and 50 per day). They attributed this change to several factors associated with urbanization: fertility rate decline, educational attainment increase, and rise in formal labor force participation (mainly in the public service, health, and educational sectors) (Ferreira 2013 147,167-179). While this trend saw setbacks in the 2008 recession and in the after-effects of the COVID-19 epidemic, the middle-income groups have slowly returned to their 2019 levels (Mahoney 2024,9). Meeting the needs of middle-income city dwellers has resulted in an increased demand for housing and improved public services, including electricity, water and sanitation, transportation, and open space.

In addition, middle-income groups' continuing expectations for well-functioning public services in their cities have led to more tolerance for increasing local source revenues (e.g., property taxes) to assure funding for new projects and for creating special-purpose vehicles for service delivery. These trends have raised the political and economic importance of local governments throughout Latin America. They have also increased the need for technically able local administrators. Finally, smoothing multi-level governmental cooperation is also a requirement for strengthening subnational finance and urban-level investability.

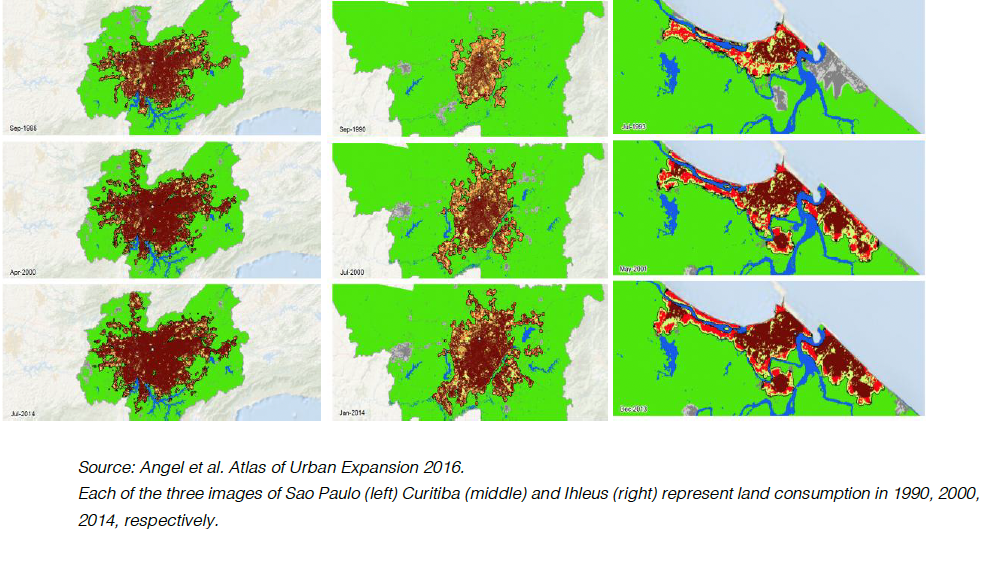

1.3. The spatial dimensions of urbanization

The largely unmanaged growth of land use among the region’s cities has resulted in widespread sprawl, measured by the ratio of city rates of land consumption to population growth rates. The Atlas of Urban Expansion documents this phenomenon [7]. In Brazil alone, the Atlas assessments of large, medium, and small cities between 1988 and 2014 reveal its extent. In 2014, São Paulo’s population (22 million) had grown by 16 percent since 1988, while its land consumption increased by 58 percent. In the same period, Florianopolis’s population (533, 000) was up 87 percent while it consumed 188 percent more land; Jequie (population 123,000) increased its residents by 4 percent while its land area grew 112 percent; Ilheus (population 97,000) had a 10 percent growth in population accompanied by a 340 percent increase in land consumption. Even in Curitiba (population 2,728,388), noted for its enlightened urban planning, the population grew by 98 percent between 1990 and 2014 while its land consumption increased by 127 percent. See Figure 2. These data provide evidence for the nature and location of increasing gaps in transportation, energy, water, and sanitation infrastructure, all in need of ameliorative investment.

Figure 2. Urban Expansion of Sao Paulo, Curitiba, and Ihleus, Brazil

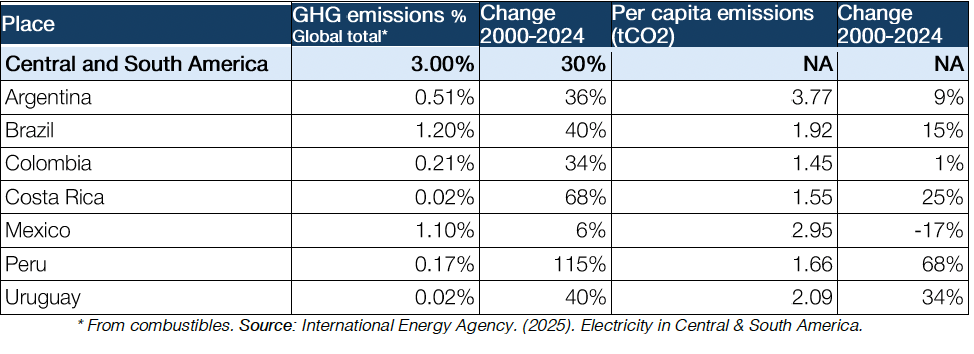

1.4. Climate change disruptions and impacts

Accompanying high urbanization rates are high rates of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the region, where some 70 percent of current emissions come from cities, with transport and electricity being the major sources. Although collectively a very small percentage of the globe’s GHG emissions, in the coming years, the region’s GHG emissions will rise despite efforts of several countries to meet their respective nations’ goals for increasing renewables (IEA 2025, 142-152). The major emitters in the region are Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina (World Bank Group, nd, 3). See Table 3.

Table 3. GHG emissions in select Central and South American countries 2000 - 2024

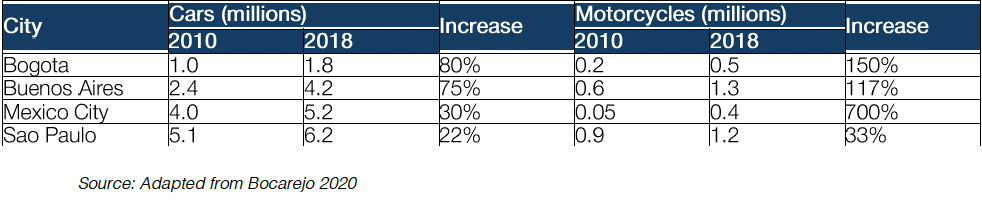

Transport is a major source of GHG emissions. For example, it is the source of 61 percent of the emissions in Sao Paulo, 38 percent in Bogota, 30 percent in Buenos Aires (World Bank Group, nd, 14). A contributing factor is the rapid growth of private fossil fuel vehicular transport, coupled with low taxes on fuel, investment in vehicle infrastructure, and robust second-hand vehicle markets. (Bocarego 2020,7, Avery and Caraballo 2019 ). Bogota and Buenos Aires nearly doubled the number of cars, while Mexico City and Sao Paulo had increases of more than a million such vehicles. See Table 4.

Table 4. Growth of Fossil Fuel Vehicular Transport in Four Major Cities 2010-2018

The growth in vehicular transport has occurred simultaneously with the institution of bus rapid transit (BRT) systems in these cities. Bogota was the pioneer with its system opening in 2000; Mexico City followed in 2005, then Sao Paolo (in the 2000s) and Buenos Aires (2011). Countrywide, some 53 BRT systems exist (34 in Brazil, 12 in Mexico, and 7 in Colombia) – but in total, they transport only 20 million people daily (Mangones et al. 2025,6). Further, public transport has low overall coverage in the region with only 10 km of public transport per million inhabitants, compared to 35 km per million in Europe (World Bank Group, nd 14).

These data indicated room for further investment in public transportation. Large city public transit systems could be expanded. Small and medium cities which have fewer transit systems have a culture of ad hoc variously named private mass transit systems – buses (pesero), cars (colectivos or carritos por puesto), motorbikes (moto-taxi) – that could bear further investment (Avery and Caraballo 2019).

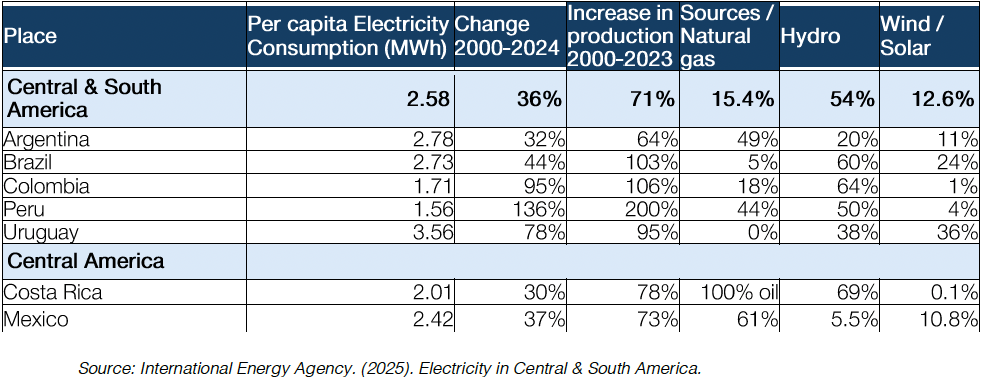

The second source of urban GHG is electricity use. The IEA anticipates a 2.2 percent annual rate of increase to 2028 in the Americas (including North, South and Central America). It highlights countries that will surpass this number, estimating, for example, a 3 - 4 percent increase in Brazil and Mexico (IEA 2025, 142 ff). In these places, residential districts’ demand for lighting, air conditioning, energy-consuming water and sanitation systems, and demand from commercial and industrial areas with modern business buildings and factories is fueling these changes. (Daunt and Siedentop 2025, IEA 2025).

While the region has the highest dependency on hydroelectric power in the world, it also suffers from droughts that have huge impacts on this source. See Table 5. For example, in May 2024, Mexico had a series of rolling blackouts that crippled cities in 18 of its 32 states; Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia faced similar challenges as the hydro powered plants could not keep up with the demand. These shortages have led to increases in the use of fossil-fueled electricity to fill the gap (Rodriquez and Yoon, 2024; Kemp, 2024). Again, these conditions offer opportunities for investment in energy transitions across Central and South America.

Table 5. Electricity: Consumption, Production and Sources

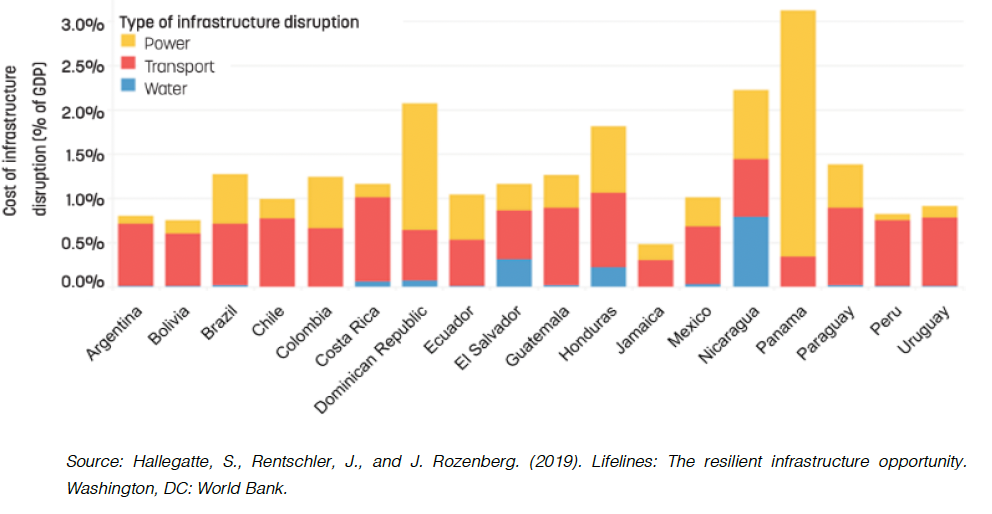

Climate change adaptation has also become important in the region’s cities, where the increase of climate-related disasters is causing infrastructure damage, whose estimated costs amounted to one percent of the region’s GDP in 2020 (World Bank Group n.d., 1). Some 80 percent of the damages are occurring in urban areas, and as seen in Figure 3, disruptions to transportation were major in 15 of the 18 LATAM countries. Power came in second, and flooding, third. (World Bank Group n.d., 3,5)

Figure 3. Cost of Climate-Related Infrastructure Disruptions to Firms 2020

1.5. Political decentralization - transitions to democracy in the 1980s

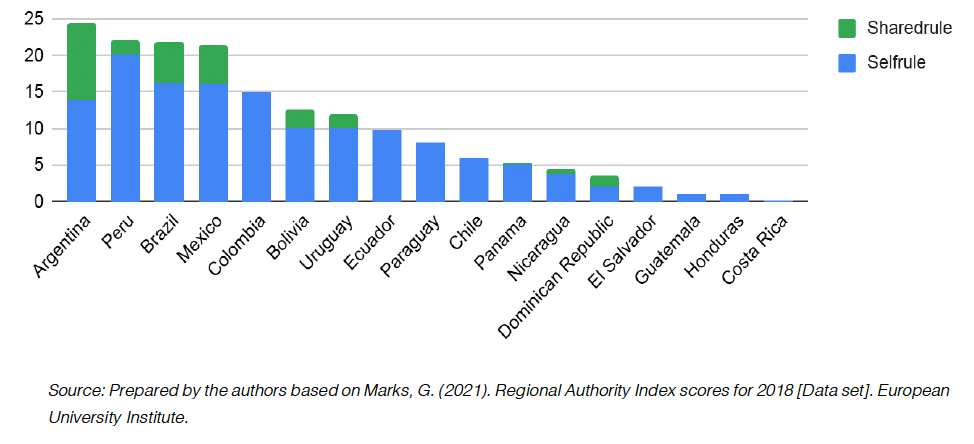

A wave of democratic transitions swept through Latin America in the 1980s, beginning with the Dominican Republic and Ecuador in 1978 and continuing through Peru, Honduras, Bolivia, Argentina, El Salvador, Guatemala, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, Panama, and finalizing with Chile in 1990. Political reforms came hand in hand with the adoption of new constitutions in Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, Colombia, Paraguay, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Guatemala, and Nicaragua between 1979 and 1994. These transitions kick-started policy and fiscal decentralization processes in many countries in the region between 1985 and 2015, often required by the IMF and World Bank as a condition for financial support, resulting in subnational governments gaining expanded roles in managing public expenditure. Figure 4 below shows the Regional Authority Index scores of 17 Latin American countries. This index provides a method for measuring the level of decentralization of a country, where higher scores indicate greater decentralization. The index assesses two dimensions of regional authority: self-rule, meaning the authority that a regional government exercises over its population; and shared rule, which reflects the authority that the region or its representatives exercise in the country. Argentina, Peru, Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia rank highly here.

Figure 4. Regional Decentralization Ranking by Regional Authority Index Scores

1.6. Fiscal decentralization trends

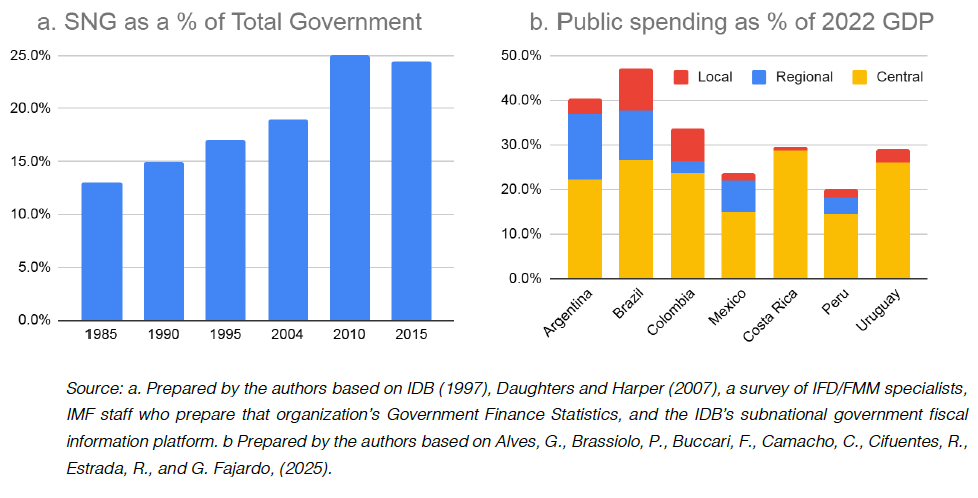

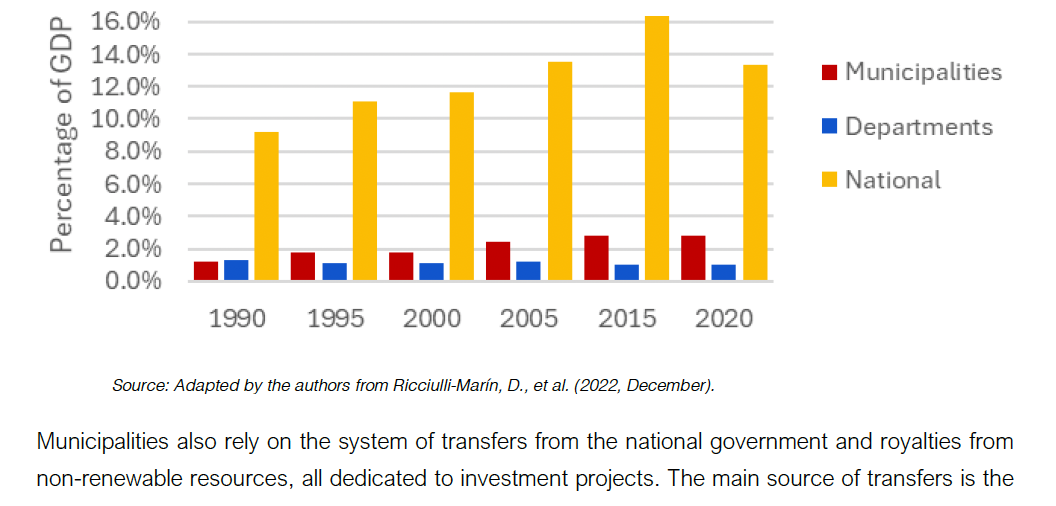

A review of fiscal decentralization from national to municipal governments is the foundation of any assessment of municipalities' ability to take on debt and manage it responsibly. The IDB categorizes governments throughout the region in three categories related to their levels of decentralization. Federal countries are Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Unitary countries with a high level of decentralization are Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Unitary countries with a lower level of decentralization are Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and all Central American and Caribbean nations. It should be noted that Uruguay has made significant recent progress in the realm of decentralization, with the creation of the municipal level of government in 2009 and continued progress since then. Between 1985 - 2015 the share of total public expenditure managed by subnational governments throughout the region jumped from 13 percent to 25 percent. Figure 5 below details this trend. This average, however, hides the fact that rates vary by country. For example, as of 2015, more than 40 percent of total public expenditure in Brazil and Argentina was managed by subnational governments, while this figure stood at less than 5 percent in Costa Rica and Uruguay.

Figure 5. Proportion of Subnational Government within Public Expenditure and GDP

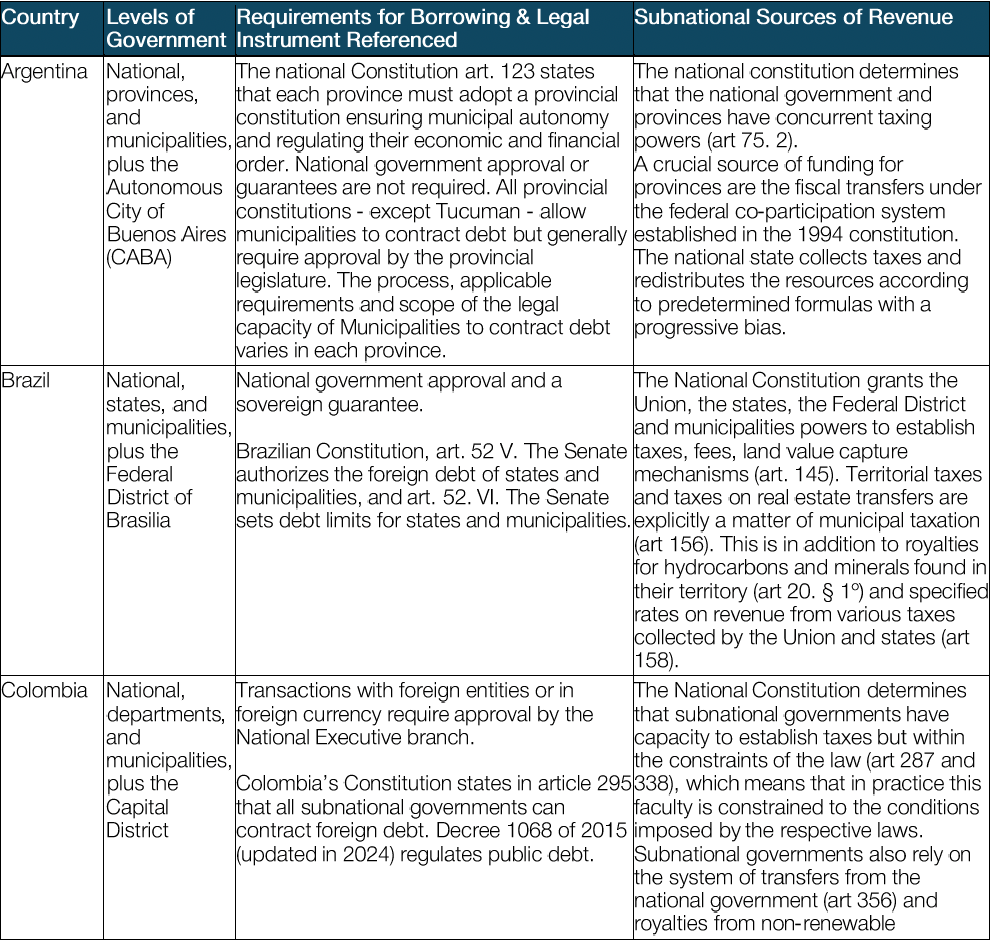

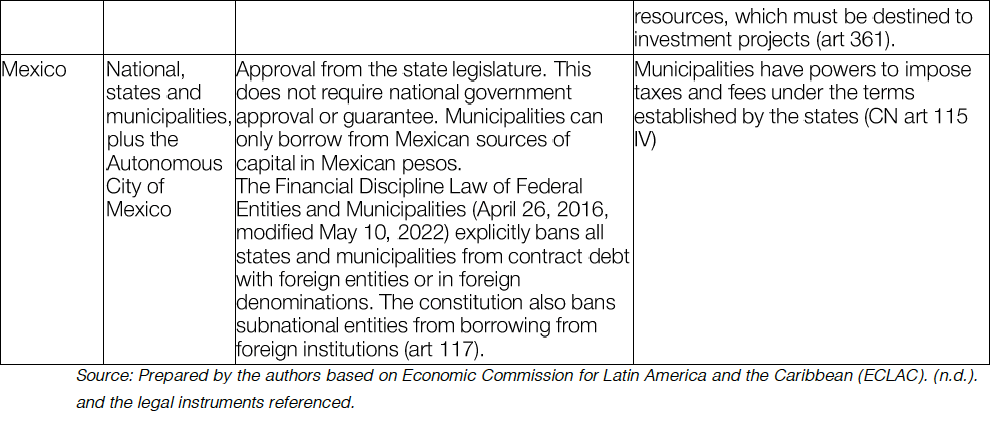

1.7. Regulatory frameworks for local borrowing

Fiscal decentralization does not necessarily allow municipal access to debt financing. Globally, only 44 percent of countries allow subnational governments to access debt financing. With that said, subnational governments can legally borrow domestically in most Latin American countries. Fewer are allowed to access international financing. In practice, many central governments restrict subnational governments from accessing debt by requiring national government approval and/or a sovereign guarantee for any debt transactions. For countries that heavily restrict subnational borrowing, there are alternative ways to attract investment for urban infrastructure, such as through state-level, government-sponsored enterprises (GSE) like utility companies, non-profits, and the private sector. The GCGF could provide guarantees to these entities where it is not possible for cities to directly access capital.

1.7.1. Enabling Environments for Public-Private Partnerships

Another consideration for the launch of a GCGF pilot in Latin America is the national and subnational enabling environment for Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs). Access to green city guarantees, particularly in mature markets, can help cities rethink how to structure and de-risk PPPs to support their public service goals.

Municipal PPPs can be used across all sectors, including waste management, public transport, water supply, and health. As such, it is an important and innovative tool for municipalities. However, harnessing the private sector for smaller-scale municipal projects poses some significant challenges for governments, particularly for those with little private sector partnership experience. Like national governments, cities need supporting legal regulations and institutions as well as human resource capacity to prepare project bids, evaluate and negotiate proposals, structure financing and risk management, monitor contracts and compliance, and evaluate ex-post impacts and outcomes. With the breadth of partnership models across sectors, cities also need the capacity to think strategically and creatively about their assets and how public and private risks, costs, and benefits should be shared in different contexts.

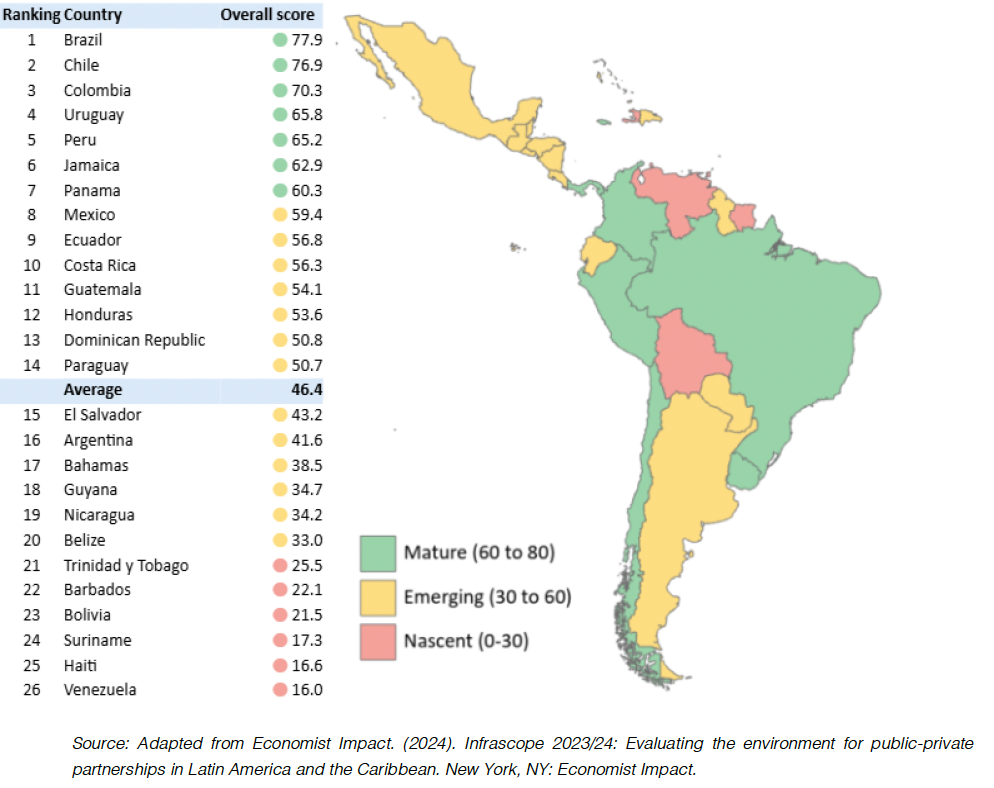

National regulations and market experience with PPPs as an investment vehicle are preconditions for municipal government partnerships. Under a 2023-2024 assessment by Infrascope with support from IDB, proposed pilot countries Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay, and Peru occupy 4 of the top 5 positions in the regional ranking and qualify as “developed” markets for PPPs. Mexico and Costa Rica are listed as emerging markets. Argentina’s PPP frameworks at the time of this assessment were not on par with the similarly sized economies of the region, which the report attributes largely to volatile political commitment to PPPs (Figure 6). Funding institutions like the World Bank and the Global Environmental Fund (GEF) and city networks like C40 recognize the importance of municipal PPPs and are working to increase capacity, developing guides, tools, and policy recommendations for cities and national governments.

Figure 6. Assessment of enabling environments for PPPs in Latin America 2023-2024

Part 2. Pilot Country Profiles

As a result of urbanization and democratization trends and increased fiscal and regulatory decentralization, Latin America has several mature and growing subnational debt markets with potential for piloting the GCGF. The following overview of four proposed countries for GCCF pilots will require further in-depth technical studies on the characteristics of select municipal debt markets in the region.

2.1. Proposed country pilots

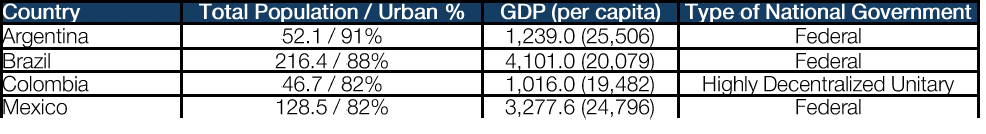

Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico are proposed for deploying the GCGF. The four countries have the largest and most developed subnational debt markets in Latin America. Table 6 offers country profiles on the four promising candidates. Table 7 summarizes the borrowing requirements for subnational governments in these four countries.

Table 6. Country Summary Data

Table 7. Requirements for Subnational International Borrowing

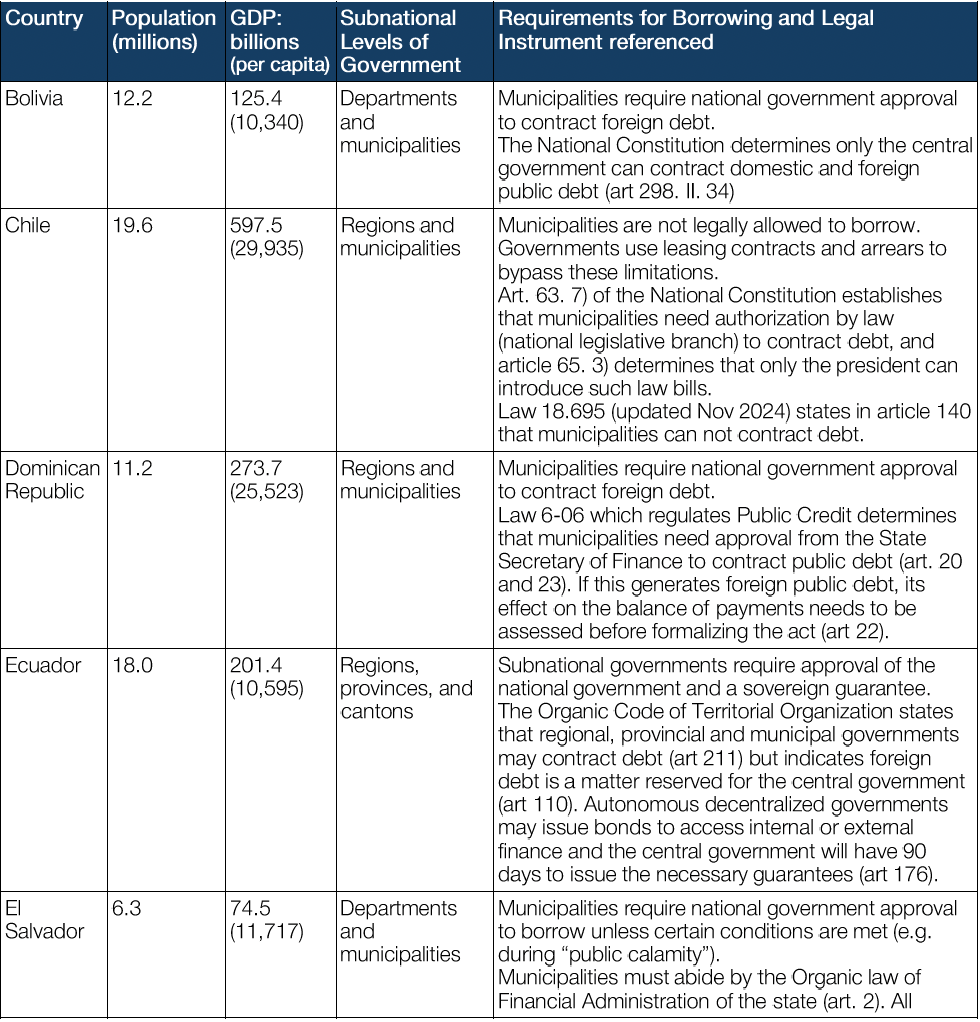

2.2. Alternate pilot countries

Several other countries throughout the region have some local government debt activity but have not established a subnational debt market at scale. These countries include Bolivia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Peru, and Uruguay. While the municipal debt markets in these countries have not reached a meaningful size, any debt activity for local governments is a positive signal as it indicates a level of openness to subnational borrowing from national governments. Three of these countries - Costa Rica, Peru, and Uruguay, are considered as alternative options for pilots. Additional information on economies not recommended for pilots is in Appendix A.

2.2.1. Argentina

2.2.1.a. Subnational Governance, Regulatory and Legal Environments

Argentina is the most decentralized national government in Latin America, with two levels of subnational governments, provinces (24 plus one autonomous city) and municipalities (2,811). The provinces have the constitutional right to define the role and responsibilities of municipalities within their jurisdiction. According to the IDB[8], subnational power structures and politics plays a very large role in national politics and governance, and ultimately fiscal decentralization to cities. As of 2023, the shared tax system distributes funds as follows: 40 percent to the national government, 57 percent to the provincial governments, 1.4 percent to Buenos Aires City (Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires - CABA, not to be confused with Buenos Aires Province), and the remainder to a national treasury fund. This balance reflects the distribution of decentralized responsibilities and powers. Provincial governments are responsible for health, education, security, transportation, and recreation.

2.2.1.b. Subnational Sources of Revenue

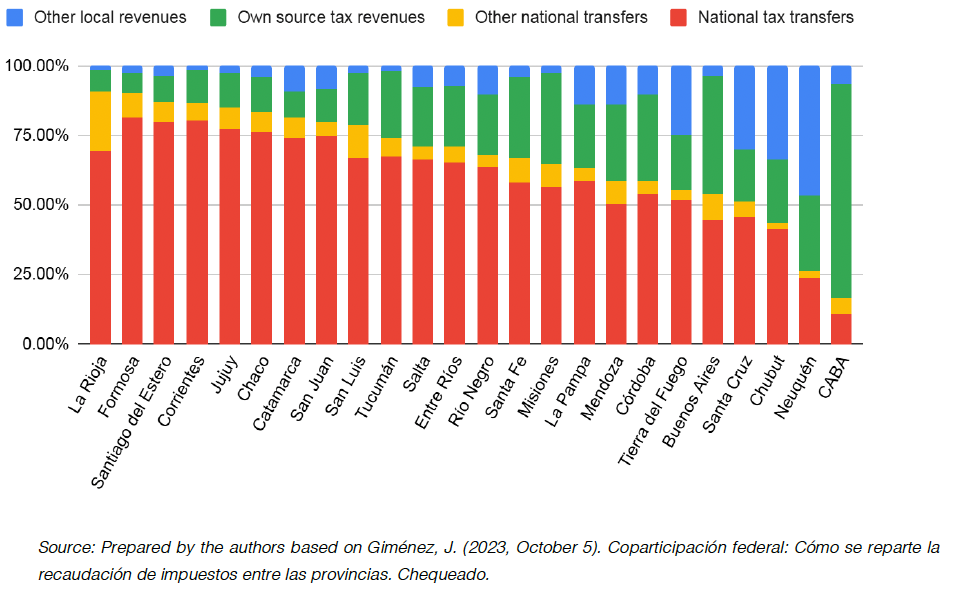

The provinces rely on a combination of fiscal transfers and their own source revenue, including goods and services and royalties from natural resources like minerals, natural income, property, vehicles, and stamp duty taxes. Municipalities can collect service fees and may establish taxes depending on their provincial legal framework. They also receive fiscal transfers from provincial and national governments. See Figure 7.

Figure 7. Argentine Provinces with Tax De-centralization at the Municipal Level

The federal co-participation system plays an important role in this equation. In 2023, co-participation made up roughly 45 percent of provincial revenues, and other federal transfers provided an additional 9 percent of provincial budgets on average [9]. However, a huge variation exists in the degree to which provincial budgets depend on federal transfers, ranging from 90 percent for La Rioja province to 16 percent for CABA in 2022 (see Figure 8). In fact, in 2022, CABA received only $11 in co-participation for every $100 contributed to the system.

Figure 8. Structure of Provincial Revenues, Argentina 2022

The provincial governors and the national government signed a fiscal pact between 2017 and 2018 reducing discretionary national funding to provinces; in 2024 it cut discretionary spending to provinces by 98 percent (roughly 5.5 percent of subnational funding).

2.2.1.c. Sub-Sovereign Debt and Creditworthiness

In all provinces except one (Tucumán), municipalities are legally allowed to contract debt. Most will contract with domestic lenders and the national treasury. Municipalities in Argentina have been leading the charge with innovative transactions that support municipal development of green projects. For example, the municipality of Godoy Cruz, which has a population of 183,000 inhabitants, is in the process of issuing a green bond to finance the expansion of Godoy Solar Park. This financing and project development is aligned with the city’s Local Climate Action Plan titled, “Godoy Cruz Carbon Neutral 2030” [10]. In 2022, the municipality of Córdoba issued over USD 18 million in green bonds to finance green infrastructure development [11]. Credit ratings are available for subnational governments in Argentina, including several provinces, CABA, and the Municipality of Cordoba [12]. Perceptions of risk for subnational governments include the risk of the sovereign interfering with the ability of domestic issuers to access, convert, and transfer money abroad, revenue robustness, individual credit quality such as resilient fiscal outcomes, adequate debt and liquidity management, fiscal imbalances and inflation, the gap between the official and blue chip exchange rate, structural reforms, and general economic instability. As of April 2025, the Milei administration has progressively taken steps to revert currency exchange controls imposed by previous administrations [13].

2.2.1.d. Implications for Cities

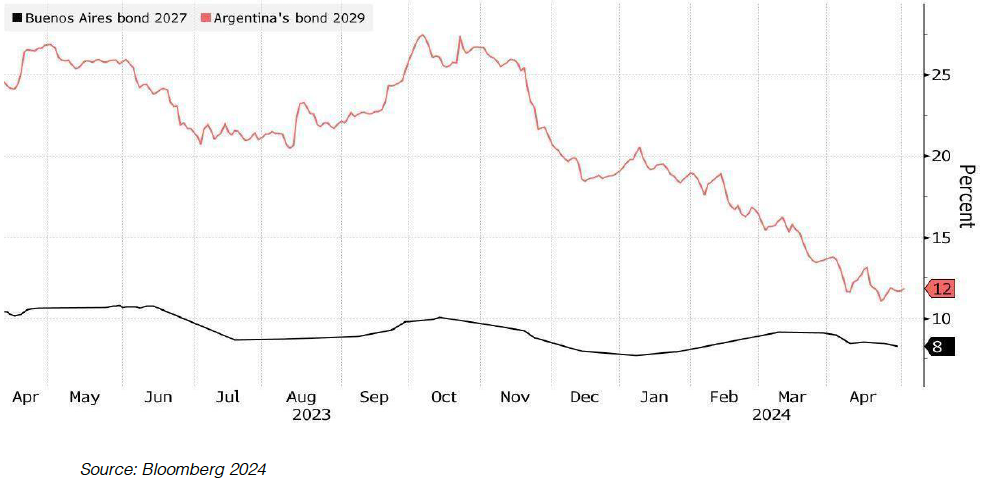

Provinces and cities with steady revenue sources can be less volatile than the national government, undercutting the perception by investors that they carry more risk. Although creditworthiness is capped by sovereign ratings, decentralized revenue generation and spending means local debt management could be assessed with greater autonomy from national conditions [14]. The CABA [15] is an example on how local governments can be more stable financial entities than national governments. As shown in Figure 9, between April 2023 and April 2024 Argentina’s sovereign bonds were marked by extremely high volatility, yielding 27 percent at their high and 11 percent at their low over this period. By contrast, from April 2023 to May of 2024, the CABA’s bonds yielded between 7 percent and 11 percent, a much narrower range than that of the national government [16]. Additionally, the November 2023 presidential election had a negligible impact on CABA bonds, reinforcing the notion that well-managed cities can be sheltered from fluctuations at the national level – this can be especially true in decentralized federal fiscal frameworks like Argentina.

Figure 9. Buenos Aires City’s Yield is Lower Than National Government’s

Despite the CABA example above, in 2024, Fitch Ratings Agency rated Argentina subnationals as highly volatile with ‘CC’ or ‘CCC’, due to the macroeconomic risks of high inflation, currency depreciation, and the operational pressure of the country’s international bond payment obligations. However, in early 2025, ratings for the national and subnational governments were being reviewed as a result of shifts in policy under the Milei administration. In February 2025, S&P raised credit ratings for Argentina from 'CCC' to 'B-', causing an immediate similar reassessment of the ratings for CABA and the provinces of Mendoza, Neuquen, Jujuy, and Salta [17].

Although CABA would likely not need a guarantee for a standard bond issuance[18], the GCGF could potentially support a city like CABA with a debut green bond issuance on global markets. This would be a new transaction for CABA, and the city would likely need some technical assistance in structuring the issuance, as well as establishing a framework for reporting on the use of proceeds toward green projects[19].

2.2.2. Brazil

2.2.2.a. Subnational Governance, Regulatory and Legal Environments

In Brazil, subnational governments (26 states plus Federal District and 5,570 municipalities) are legally allowed to borrow from both domestic and external lenders, but all foreign debt transactions by all levels the government (the “União” or Union), must be approved by the External Financing Commission (Comissão de Financiamentos Externos – COFIEX), a body under the Ministry of Planning and Budget. Additionally, a series of borrowing constraints are imposed on subnational governments by the central government to ensure sound debt management practices. As of 2020, Brazil had USD 229 billion in outstanding debt across its subnational governments. Local governments account for 15.8 percent of this figure, or USD 36.2 billion, with state and regional governments accounting for the remaining USD 192.8 billion.

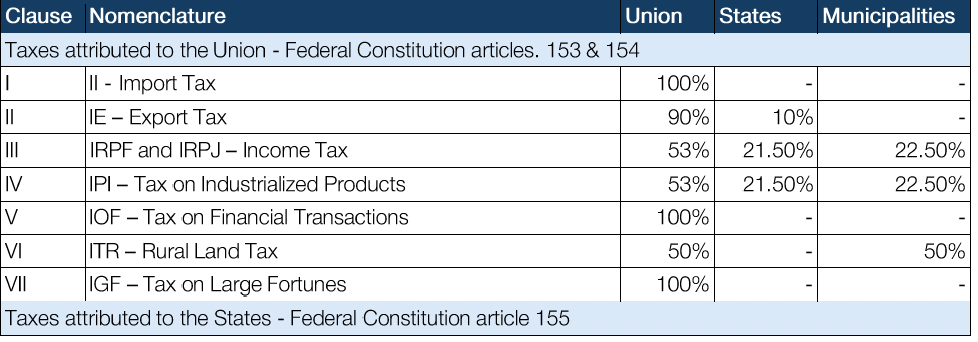

2.2.2.b. Subnational Sources of Revenue

The states, the Federal District and municipalities have powers to establish taxes, fees, and land value capture mechanisms. States and municipalities also collect royalties or compensation for oil, natural gas, minerals and hydropower exploitation in their territory, as well as specified rates on revenue from various taxes collected by the Union and states. The laws have determined schemes whereby the three levels of government share certain taxes in different ratios. Territorial taxes and taxes on real estate transfers are explicitly a matter of municipal taxation, and together with taxes on services they are the most important taxes collected by municipalities, though they are more challenging to collect than other taxes [20]. See Table 8.

Table 8. Taxation Powers and Distribution among Levels of Government in Brazil

However, most Brazilian municipalities have limited capacity to raise their own revenues and are highly dependent on fiscal transfers. The States’ Participation Fund and the Municipalities’ Participation Fund are the two main sources of direct transfers to the two levels of government, accounting for 64.9 percent and 57.7 percent of federal transfers to states and municipalities respectively in 2024 [21]. These funds seek to balance fiscal capacity across regions and constitute the main source of revenue for states like Acre, Amapá, Roraima, and Tocantins. In some municipalities in Brazil, municipal taxation may account for as little as 3 percent of municipal budgets, with 97 percent of their revenue coming from federal and state transfers.

2.2.2.c. Sub-Sovereign Debt and Creditworthiness

Domestic public lenders are the primary source of debt for municipalities in Brazil. The Union, the Federal Savings Bank, the Brazilian Development Bank, and the Bank of Brazil are the major domestic lenders. International lenders account for 7.6 percent of municipal debt in Brazil, with the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and CAF being the major sources for municipalities. In 2016, the Brazilian government launched Programa de Parcerias de Investimentos (Investment Partnerships Program), which provides technical assistance funding to local governments to develop PPPs. The Brazilian Development Bank manages this fund and plays a crucial role in the national public debt market, accounting for 92 percent of total PDB assets in Brazil. This is one example of how the Brazilian government supports cities in directly accessing capital for infrastructure [22].

According to Brazil’s regulatory frameworks, subnational government creditworthiness is capped and may not be rated above the sovereign government rating, a standard rating driver regardless of the fiscal level of decentralization. According to the Fitch Rating Agency, subnational ratings in Brazil are heavily influenced by national regulatory control over subnational spending and tax policy. Like other countries, the perceptions of risk for subnational governments include the risk of the sovereign interfering with the ability of domestic issuers to access, convert, and transfer money abroad, individual credit quality such as resilient fiscal outcomes, adequate debt and liquidity management, fiscal imbalances and inflation, the gap between the official and blue-chip exchange rate, structural reforms, and general economic instability. Additionally, credit rating agencies are increasingly looking at how climate risks assessments impact fiscal frameworks and policy within their ESG frameworks, with implications for subnational creditworthiness.

2.2.2.d. Implications for Cities

Although they are allowed to raise internal and external debt, municipalities have little or no access to the international credit market. The largest constraint, however, is that all nondomestic financial transactions with municipalities must be authorized by the External Financing Commission and municipal debt is constrained by Brazil's Fiscal Responsibility Law, which sets parameters on debt ratios, performance and management.

The Metropolitan Region of São Paulo (RMSP), with over 20 million inhabitants, does issue municipal bonds, and Fitch currently rates them as stable ‘BB’. In general, Brazil’s sub-sovereign creditworthiness reflects the national credit profile, but it can vary based on specific risks. However, according to the World Bank City Creditworthiness Initiative [23] Brazilian municipalities face two main constraints on debt: (i) a maximum of 100 percent of real liquid revenues (under Law 9496 of 1997) and (ii) 120 percent of net current revenues (under Federal Senate Resolution 40 of 2001).

2.2.3. Colombia

2.2.3.a. Subnational Governance, Regulatory and Legal Environments

In the early 1990s, fiscal decentralization measures were passed in Colombia, which made regional (32 departments plus one capital district) and local (1,103 municipalities) governments larger players in the economic development of the nation [24] Today, Colombia has one of the most active subnational debt markets in Latin America.

The Colombian constitution establishes that subnational governments can take on external debt [25] and that all local government debt must be approved by the national government [26] National regulations determine that the National Council for Economic and Social Policy (Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social - CONPES), within the National Planning Department is the entity tasked with approving the foreign credit transactions and any guarantees issued by the national government in the cases where they are required [27].

Colombia is also a global leader in financial innovation. In 2022 the country launched its Green Taxonomy (the first in the Americas) and has since undertaken important efforts to build local capabilities for its adoption. It has developed and published implementation tools in collaboration with the Climate Bonds Initiative that include identification strategies and guides and the delivery of technical assistance to subnational actors and stakeholders in the financial and real estate sectors [28].

2.2.3.b. Subnational Sources of Revenue

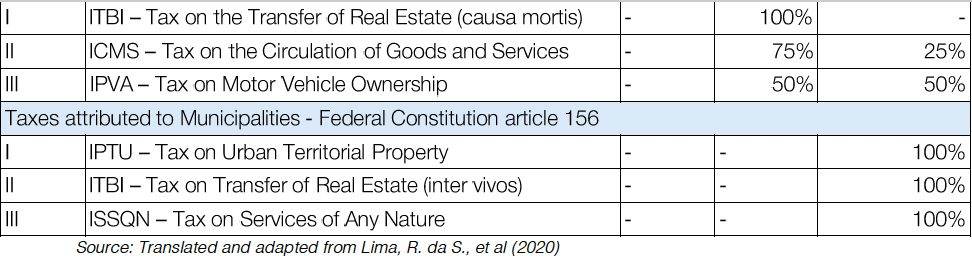

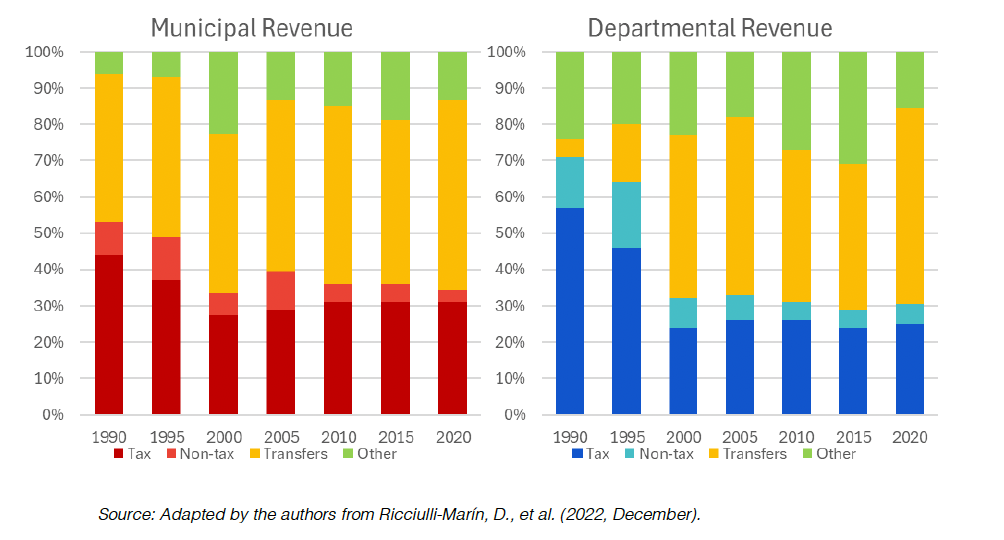

Subnational governments have the capacity to establish taxes within the constraints of the specific laws authorizing each such instance. In practice, these restrictions severely limit the scope of municipal taxation capacity. Departments collect taxes on alcohol, tobacco, vehicles, gasoline, and other fees. Municipalities can tax real estate, industry, and trade, and collect fees for certain services. See Figure 10.

Figure 10. Own Source Revenue (tax and non-tax) by Level of Government in Colombia

Municipalities also rely on the system of transfers from the national government and royalties from non-renewable resources, all dedicated to investment projects. The main source of transfers is the General Participations System, which allocates resources to municipalities based on a formula based on population, social equity, and efficiency criteria. These transfers are used to finance services provided by municipalities and subnational governments, including education, health, water and sanitation, among others. In some municipalities, the General Participations System transfers amount to 60 to 70 percent of total revenues. See Figure 11.

Figure 11. Composition of Municipal and Departmental Revenues in Colombia

In December 2024, the National Congress approved a constitutional reform that promises to transform the national/subnational balance, increasing revenue transfers and decentralizing authority to governors and mayors. The changes aim to increase the funds to be distributed from 24 to 39.5 percent of the national budget over a 12-year period. The reform will put Colombia in line with Brazil and Argentina in terms of subnational finance, significantly expanding the resources available to subnational governments[29].

2.2.3.c. Sub-Sovereign Debt and Creditworthiness

Colombia’s national development bank system is active[30]. Financiera De Desarrollo Territorial S.A. (Findeter), the national development bank (established in 1989), operates as a mixed public-private stock corporation with 90 percent owned by the Ministry of Finance. Overseen by the national Financial Superintendency, it plays an important role providing access to development finance to Colombian cities[31] Established in 2011, Financiera de Desarrollo Nacional (FDN, previously known as Financiera Energética Nacional) is an example of the country’s second national development bank. Two thirds owned by the national government and the remainder by such strategic investors as CAF and IDB, it focuses on large scale national infrastructure projects [32].

Besides relying on local entities like Findeter, some of the largest cities, such as Bogotá, Barranquilla, and Medellín, have successfully issued bonds in global capital markets in recent years. They are all mandated to follow strict national government guidelines to ensure sound fiscal management by local governments.

Credit ratings for municipalities in Colombia are strongly impacted by national credit risks, including macroeconomic stability. However, rating agencies will consider local economic variables like revenue projections, tax collection patterns, liabilities, fiscal management, and the vitality of local economy sectors such as tourism or manufacturing. Major cities in Colombia, such as Bogota, Medellin, and Barranquilla are typically rated BB as assessed by ratings agencies.

2.2.3.d. Implications for Cities

Cities in Colombia are demonstrating that they have the fiscal profiles and management capacity to handle international bonds. In May 2023, during Jaime Pumarejo’s33 mayoral term, the city of Barranquilla issued USD 156 million in local bond notes with an average interest rate of 9.9 percent. Fitch assigned Barranquilla a National Long-Term Rating of ‘AA (Colombia)’ and a Stand-Alone Credit Profile of ‘BB’. This reflects that relative to domestic issuers of bonds in Colombia, Barranquilla is considered a highly safe issuer. However, compared to the universe of public finance issuers across developed and developing markets, Barranquilla has a somewhat risky profile. Fitch’s analysis of Barranquilla’s financial profile scored the city’s Revenue Robustness as Weaker, a ranking mainly attributable to uncertainty around the plight of national government transfers to Barranquilla under President Gustavo Petro’s administration. However, Fitch also highlights Barranquilla’s tax collection growth that helps to counter any adverse impacts from the national government. Regarding currency risk, while 36.8 percent of Barranquilla’s long-term debt is in US dollars and euros, the city has engaged in currency swaps to mitigate the impacts from exchange rate fluctuations.

2.2.4. Mexico

2.2.4.a. Governance, Regulatory and Legal Environment

In the early 2000s, major economic reforms led to the rapid growth of the subnational debt market in Mexico. The Mexican constitution bans subnational governments (31 states plus Mexico City and 2,480 municipalities) from contracting debt with foreign institutions and a separate law also bans these entities from borrowing in foreign currencies. This means municipalities and states can only contract debt or issue bonds in local currency (Mexican pesos) and with national entities - a restrictive but effective means to avoid foreign exchange risks. On the other hand, the national government established the Master Trust Funds (MTFs), a debt service fund that imposes a mandatory set-aside used for repaying bonds. This requirement adds an extra layer of risk mitigation for investors and enables local governments in Mexico to borrow against future federal transfers, significantly de-risking subnational debt and lowering the cost of borrowing for local and regional governments. Due to this legal framework, subnational debt is not considered a national government liability, and as a result sovereign guarantees are not required or used for local government debt. This differentiates the Mexican subnational debt market from most subnational debt markets in the region. Nonetheless, all municipal debt transactions must be approved by state legislatures.

2.2.4.b. Subnational Sources of Revenue

Municipalities have limited powers to impose taxes and fees under the terms established by the states, and on average only 11 percent of municipal budgets originate own-source revenues. The real estate tax, the main tax collected by municipalities, amounts to 0.2 percent of Mexican GDP (compared to 0.8 percent in Brazil)[34].

Federal transfers represent 85 percent of state budgets on average, ranging from 97 percent for the state of Guerrero to 75 percent for the state of Chihuahua. Mexico City is an outlier among subnational entities, with federal transfers representing only 55 percent of its revenue in 2023[35].

States rely mainly on real estate taxes, water rights and other taxes on entertainment, though it is estimated that states do not apply all taxation mechanisms available to them due to the political cost associated with the imposition of taxes. Additionally, some regions lack taxable commercial activity or private property apt for the imposition of taxes on the local population, which undermines their possibility to generate own-source revenues[36].

2.2.4.c. Sub-Sovereign Debt and Creditworthiness

In Mexico, total subnational debt stood at USD 29.7 billion in 2020. However, local governments account for just 6.82 percent of this figure, or USD 2 billion. With that said, municipal debt levels in Mexico have grown steadily since 2008. From 2008 to 2018, Mexico’s municipal debt levels increased by 93.6 percent. Since 2010, Mexican municipalities have been actively working toward securing credit ratings from major ratings agencies. As of 2020, over 30 municipalities in Mexico are rated by Moody’s.

Domestic commercial banks represent the largest category of lenders to municipalities in Mexico, accounting for 50 percent of total municipal liabilities. The next largest type of lender to municipalities in Mexico is domestic development banks, representing 42 percent of municipal debt.

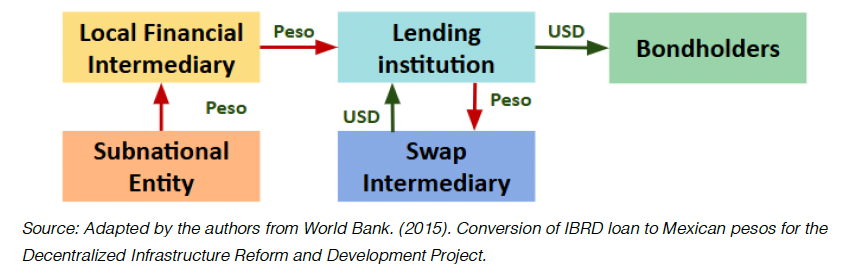

2.2.4.d. Implications for Cities

Considering the legal framework and restrictions to subnational governments, strategies to support investments in local infrastructure in Mexico should consider support for financial intermediaries. The World Bank and IDB have deployed different schemes in the past involving guarantees and other currency risk mitigation mechanisms to support debt issuances in local currency through local institutions such as BANOBRAS[37] and Sociedad Hipotecaria Federal (SHF)[38]. In 2023, MIGA issued record breaking guarantees to support projects for renewable energy, and clean transportation, among other sectors[39]. See Figure 12.

Figure 12. Financial Structure for Currency Management via Swap Market

The other set of strategies that are particularly relevant to Mexico involves supporting private sector engagement to increase investment in urban infrastructure, particularly in sectors like energy, water, and sanitation. The energy sector, in particular, has undergone significant regulatory updates since 2013, aiming to increase private sector participation and investment.

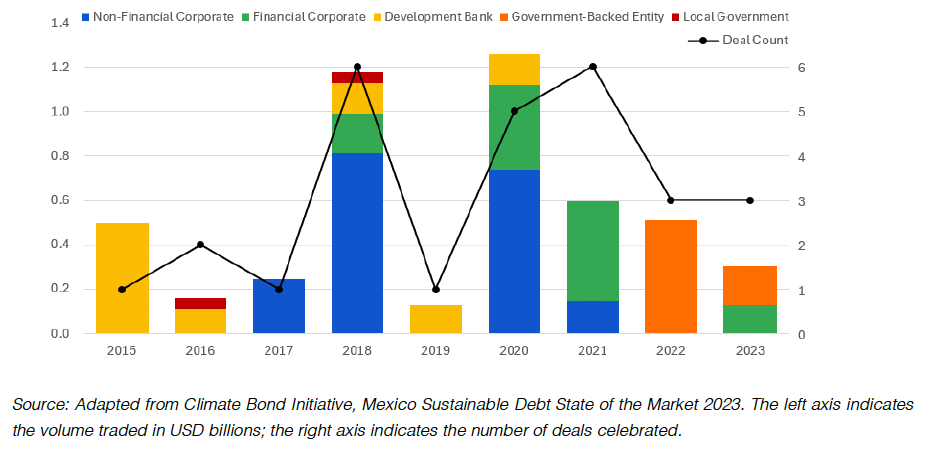

In 2024, Climate Bonds Initiative, in collaboration with the LAGreen Fund announced the "Mexico Sustainable Debt State of the Market 2023" report, which details USD 38.3 billion of cumulative issuance of Green, Social, Sustainability, and Sustainability-Linked Bonds (GSS+). Despite being the second highest issuer in Latin America and the Caribbean, the proportion of local government debt issuances in the country’s total is nearly zero (See Figure 13).40 In the last five years, the largest issuer was the private sector.

Figure 13. Sustainable Debt Structure 2023: Mexico

With their risk profiles separate from the sovereign and investment grading ratings, and general institutional knowledge of GSS+ bonds across Mexico, the risk mitigation offered by the GCGF might demonstrate the value of such an instrument to subnationals and their private sector partners in Mexico.

2.3. Alternative pilot countries

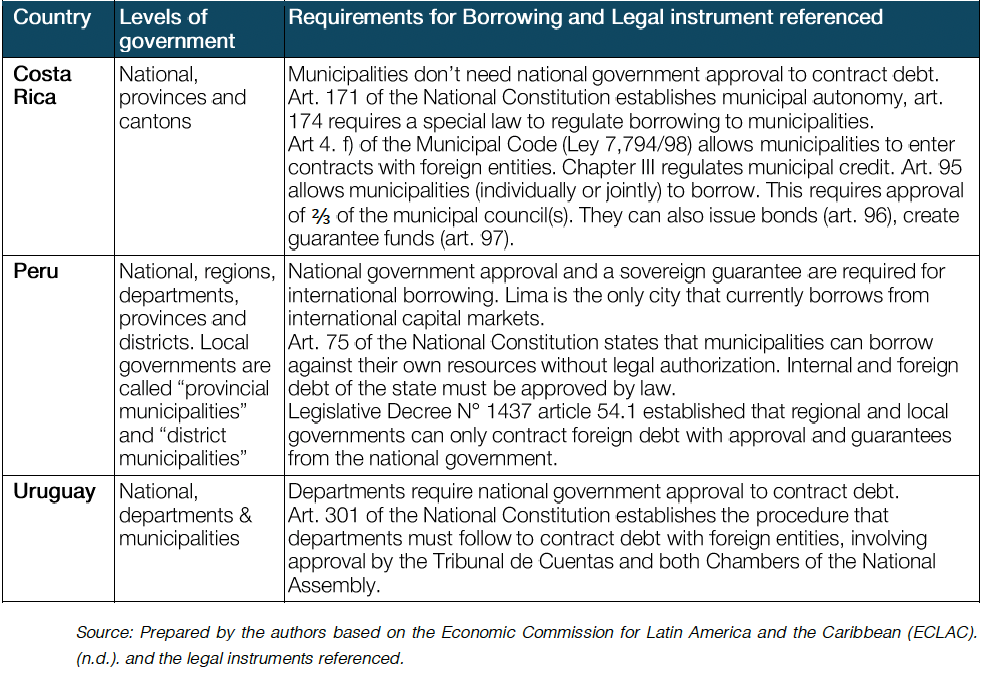

Costa Rica, Peru, and Uruguay have less developed subnational borrowing governance, policies, and experience with debt markets. Table 9 and the short profiles below highlight the current state of subnational and municipal borrowing in these countries.

Table 9. Requirements for Subnational International Borrowing in Alternate Countries

2.3.1. Costa Rica

Costa Rica’s municipalities have a relatively high degree of fiscal autonomy. The national government transfers just 10 percent of its budget to local governments, reflecting the high degree of fiscal autonomy at the subnational level. Through both tax and non-tax revenue sources, local governments in Costa Rica finance most of their infrastructure and public services on their own. Revenue sources include property taxes and fuel taxes.

Local governments are legally permitted to borrow internally and externally, with certain limits and requirements for approval set by the central government. Foreign debt requires approval from the Legislative Assembly. However, Costa Rica has a population of 5.1 million, while the capital city, San Jose, has 356,000 residents. The relatively small population and lack of major municipalities mean that cities in Costa Rica are unlikely to engage in large-scale cross-border bond issuances, as the capital requirements are not sufficient to justify these kinds of transactions. With that said, given the important powers attributed to municipalities in Costa Rica, this country represents a strong market for cities with high fiscal capacity for loans.

2.3.2. Peru

Peru has the fifth-largest subnational debt market in Latin America after Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and Argentina, with a reported USD 7.6 billion in subnational liabilities as of 2020. Local governments accounted for approximately 49 percent of this figure, with regional governments representing the remainder. However, municipalities do not generate substantial revenues internally, instead relying heavily on national government transfers. The country overall has a high-level potential given the relatively high rate of decentralized expenditure, the current size of the market being over USD 7 billion, and the presence of innovative financing instruments put in practice by the capital city of Lima.

Through a special agreement with the city of Lima, the national government of Peru allows the city to access global capital markets. However, this right is not extended to any other municipalities in the country. In 2023, Lima carried out one of Latin America’s most innovative financings at the subnational level in recent years by launching a securitization program which has thus far provided the city with over USD 650 million in funding from international investors. The 20-year bonds are denominated in local currency and listed in the Singapore Stock Exchange, enabling the city of Lima to diversify its investor base outside of Peru. This bond issuance was the first time a municipality in Peru securitized tax revenues. By executing a structured finance transaction, Lima was able to significantly de-risk the transaction from the perspective of investors. Other cities in Peru could seek to replicate this structure in the domestic market.

2.3.3. Uruguay

In 2009-10, Uruguay undertook decentralization reforms which led to the creation of municipal governments as a third level of government. Previously, departments were the only form of subnational governments. There are now 125 municipalities in Uruguay, and their main attributions and functions are defined by the national laws on decentralization and municipalities [41]. Municipalities are subject to the laws and policies of their respective departments, leading to limited fiscal and administrative autonomy, and have no taxation powers. Departmental governments can access debt both internally and externally, but require national government approval to do so. State-owned enterprises and national authorities play an important role in financing urban infrastructure as well. For example, CAF – Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean - provided a USD 15 million loan to the national transport company of Uruguay to finance the procurement of electric buses. In February 2025, CAF announced a USD 12 million structured loan agreement to finance 25 projects led by local governments in the Canelones Department (3 departmental, 22 municipal) [42] Overall, there is potential for the departmental governments in Uruguay to undertake more innovative financing to carry out critical urban projects.

Part 3. Advantages of Piloting Guarantees in Central and Latin America

Central and Latin America, particularly Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico, are suitable candidates for piloting the GCCF, because they have three advantages. They offer:

catalytic market opportunities: The guarantee industry is nascent, and the region accounts for only four percent of guarantee activity globally.

institutional commitment: the region hosts numerous public development funds ready to be leveraged for sustainable and resilient urban infrastructure projects; and

investment readiness: high levels of urbanization, sustained decentralization, and mature subnational institutions with a great need for climate-responsive infrastructure in large and intermediate-sized cities.

3.1. Catalytic market opportunity

The guarantee industry in Latin American is nascent; the region accounts for only four percent guarantee activity globally. If the Latin America region becomes the area for GCGF’s pilots, that choice could unleash a large supply of public development funds for critical urban climate resilient projects. Depending on the context, this de-risking could apply for projects undertaken by several types of sponsors including local governments, municipal utility companies, PPPs, and private companies. Regardless of the sponsor, the GCGF could catalyze the growth of local commercial debt markets, support access to global capital markets, help increase the presence of municipalities in the Green, Social, Sustainable (GSS) bond market, expand public-private partnerships at the subnational level, and encourage greater private sector investment in urban infrastructure.

Since climate finance spans a broad capital base, the GCGF could have a flexible mandate, supporting the growth of a variety of markets while attracting a wide range of investors to the urban climate finance sector.

3.1.1. Institutional Commitment to Subnational Investment

Latin America is home to significant sources of public development funds and access to capital from a base of global infrastructure investors. Cities have the support of development finance institutions publicly committed to financing subnational entities and policymakers keen to support green urban development. For example, in 2020, member organizations of Finance in Common formed an Alliance for Subnational Development Banks in Latin America led by the Banco de Desenvolvimento de Minas Gerais (BDMG), the French Development Agency (AFD), the Global Fund for Cities Development (FMDV) and the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI).

In addition, other international/external entities support subnational investments aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals. Regional multilateral development banks including CAF, with USD 50+ billion in assets, recently pledged one third of its capital to subnational governments. In 2024, IDB, with assets of USD 155 billion, announced a sectoral framework on subnational development that recognizes the importance of local government engagement, Bilateral aid offices as exemplified by the US Development Finance Corporation (DFC) that has provided capital and guarantees for local development in the past, are also in the game.

Internal sources have significant lending bases can be tapped. They include the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) with USD 131 billion in assets, Mexico’s National Bank of Public Works and Services (BANOBRAS) with USD 52 billion under management and CAF with assets valued at USD 56.5 billion. All have investment-grade credit ratings (AAA).

3.1.2. Investment Readiness for Financing Urban Investment Gaps

Although the countries analyzed in this paper present very different regulatory frameworks, market conditions, and degrees of decentralization, political conditions in the region suggest the timing is right for the establishment of the GCGF. Crucially, the four proposed focus countries represent sizable markets with very dynamic local governments that have important powers and viable options for instrumenting suitable financial vehicles like green city guarantees. In Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, local conditions include financial institutions such as national development banks that play an important role investing in local infrastructure projects. Their presence constitutes an important factor that may enable different kinds of partnerships and financial schemes to realize international financing agreements in compliance with local requirements. Relevant precedents identified in this report provide models for international project finance that have been implemented in these countries and indicate the presence of the necessary local capacity and experience.

Other relevant political conditions in the region, such as important fiscal and regulatory reforms underway in countries like Argentina and Colombia, have the potential to further improve conditions for deployment of a guarantee fund targeting subnational governments in those regions. Furthermore, the Lula administration in Brazil is also calling attention to the importance of the sustainable development agenda and working in partnership with international finance institutions and development agencies to attract finance to that agenda. Recent research on Country Platforms discusses some of the policies and collaborations to advance climate action in Brazil, including policies focused on action at the municipal level [43].

A Final Word. The Time is Right for the Green Cities Guarantee Fund: Next Steps

Urban climate finance momentum

Recently, initiatives to increase access to climate finance for cities have gained attention on the global stage. For example, in 2023 the UAE COP Presidency in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies hosted the Local Climate Action Summit, a first-of-its-kind meeting within the official COP 28 program. It focused on bringing together national and subnational leaders to transform climate finance, enhance global action, fast-track the energy transition, and strengthen resilience and adaptation at the local level. COP 28 also witnessed more than 70 nations endorsing the creation of CHAMP (the Coalition for High Ambition Multilevel Partnerships for Climate Action), which will incorporate subnational governments in the development and implementation of the next Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in 2025, a commitment with potential to significantly increase cities’ access to climate finance.

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) globally are also launching numerous efforts to support local sustainable development. Funding mobilized from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and donor countries and guarantees from InvestEU, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Green Cities program (begun 2016) have supported investment in sustainable infrastructure in more than 50 cities with more than USD 5 billion in investment [44]. The City Climate Finance Gap Fund, launched in 2020, replenished in 2023, and administered by the World Bank and European Investment Bank assists cities with technical assistance for sustainable and climate-resilient projects. So far, it has supported 183 cities in 67 countries [45].

In the policy and advocacy realms, several organizations provide data, policy advice and knowledge-sharing platforms. For example, the OECD’s Center for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Cities, and Region’s advises the G-20, public and private sector leaders and other interested parties with comprehensive up-to-date data, programs, and policies on subnational infrastructure finance. Its Financing Cities of Tomorrow (September 2023), a report for the G-20 Infrastructure Working Group under the Indian Presidency and its Infrastructure for a Climate Resilient Future (April 2024) exemplify this work [46]. UN-Habitat monitors the urban content of the NDCs, and, sponsored by Spain, has joined UNDP and other UN units to form the Local 2030 Secretariat in Bilbao (2022) to share tools, experiences, and new solutions for SDG implementation [47]. CPI, CCFLA, WRI’s Ross Center for Sustainable Cities, CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project), and the World Economic Forum’s Future Councils, also perform critical work on the cities climate finance space.

On top of these initiatives, such city networks as C40, ICLEI, UCLG, RCN- (Resilient City Networks) and such global alliances for city climate leadership such as GCoM play a pivotal role in advocating for greater access to climate finance for local governments. Together with their city stakeholders, they are actively working to bridge the gap between capital markets and urban climate finance. A wave of city focused advocacy, which includes new initiatives launched by NGOs, development banks, national governments, and the private sector reflect the momentum behind expanding urban climate finance. One example is the SDSN Global Commission on Urban SDG Finance co chaired by mayors Anne Hidalgo (Paris) and Eduardo Paes (Rio de Janeiro), and economist Jeffrey Sachs launched in June 2023 has the express purpose of finding ways to increase the flow of climate finance into cities around the world. With its secretariat, the Penn Institute for Urban Research it has developed the proposal for a Green Cities Guarantee Fund proposal discussed in this report.

The rise of guarantees and new opportunities

Research conducted over the past several years has drawn attention to guarantees in mobilizing investment in climate projects. This recognition is reflected in several key initiatives and announcements including Guarantco’s successful record of more than USD 6 billion in guarantees in the Global South over the past two decades; World Bank president, Ajay Banga’s 2023 pledge to triple its guarantees by 2030, the 2024 launch of the Green Guarantee Company aiming to shore up the green bond market in the Global South and most notably, the creation of guarantee instruments specifically for cities as exemplified by the French Development Agency’s CITYRIZ and the UN Capital Development Fund’s (UNCDF) Guarantee Facility for Sustainable Cities.

However, the city-dedicated guarantee space is nascent, and currently, no such urban guarantee fund focuses on Central and Latin America. The proposed Green Cities Guarantee Fund can fill this gap and significantly enhance financial flows toward the development of much-needed sustainable and climate-resilient urban infrastructure in the region.

Moving from Concept to Operation

To move the GCGF proposal from concept to operation requires several steps. They are:

- Develop a business plan on how to structure the GCGF including detailing governance, examining legal arrangements necessary to establish the fund, securing funding commitments.

- Conduct an In-depth market study and technical reviews of municipal opportunities for the best use of green city guarantees for climate resilient infrastructure in and facilitating access to capital for cities, even ones with limited capital market access. This includes strategies such as working with public utilities, special purpose entities or private sector partners.

- Explore how emerging changes in the international financial architecture and global economy might inform the structure of the GCGF.

- Initiate communication and advocacy strategies to promote the GCGF with key national government leaders, important urban climate networks, and at major global events.

The next report in this series will examine many of these issues.

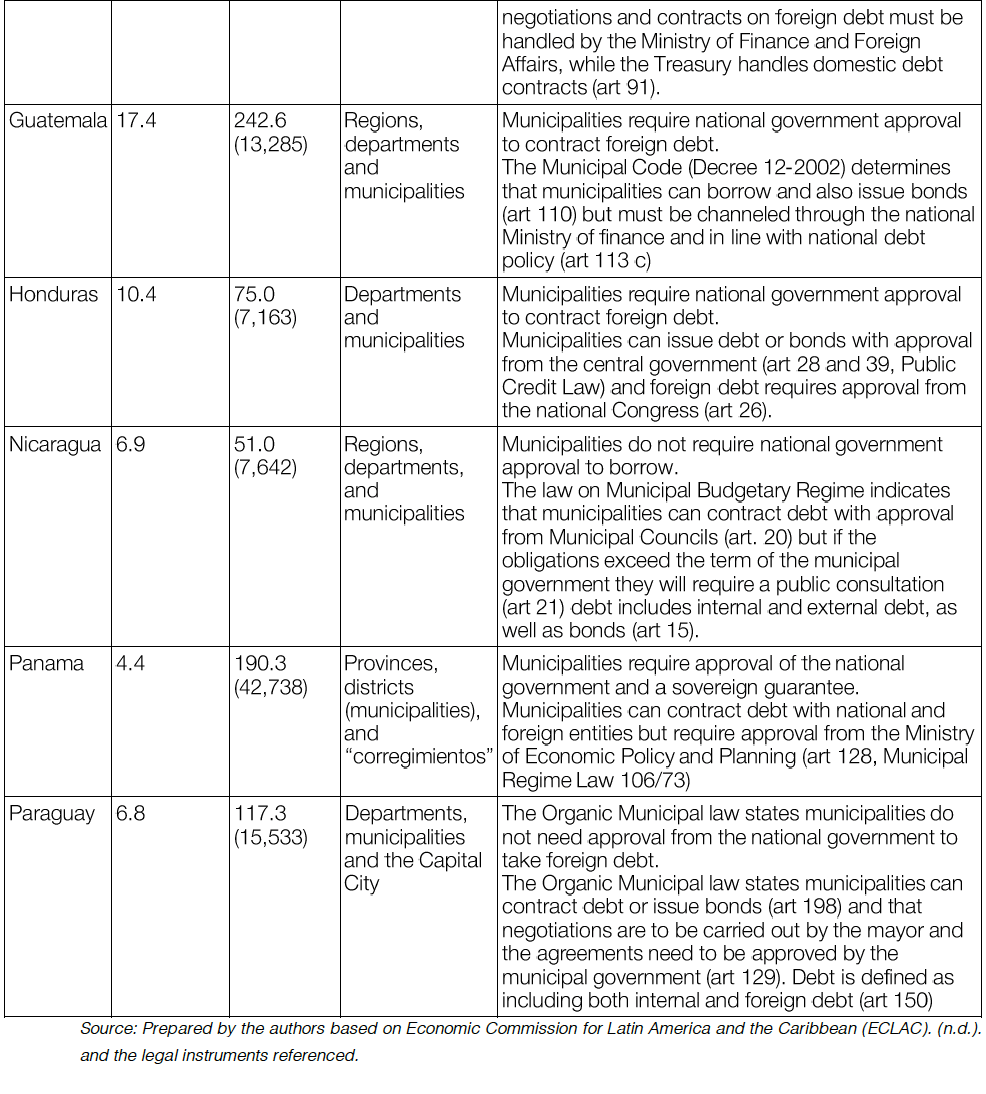

Appendix A: Overview of the subnational borrowing frameworks of other Latin American countries

The table below provides an overview of the subnational borrowing frameworks of Latin American countries not discussed in this report. The table is organized alphabetically.

Acosta, G., López Accotto, A. (Coord.), & Macchioli, M. (2015). La estructura de la recaudación municipal en la Argentina: Alcances, limitaciones y desafíos (1st ed.). Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento. https://www.ungs.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/pdfs_ediciones/La_estructura…

Agence Française de Développement (AFD). (2022). The Cityriz Guarantee. https://www.afd.fr/en/cityriz-guarantee

Aguirre, H. (2024, May 5). States only collect, on average, 12% of their revenue. Revista Cámara de Diputados. https://comunicacionsocial.diputados.gob.mx/revista/index.php/entrevist…

Almeida, M. D., & Eguino, H. (n.d.). Decentralized governance and climate change in Latin America. Inter-American Development Bank.

Alvarado, L. (2025, April 1). What is the health of the states' finances? Ethos Public Policy Laboratory. https://www.ethos.org.mx/finanzas-publicas/columnas/que_tan_sanas_son_l…

Alves, G., Brassiolo, P., Buccari, F., Camacho, C., Cifuentes, R., Estrada, R., & Fajardo, G. (2025). Soluciones cercanas: El papel de los gobiernos locales y regionales en América Latina y el Caribe. CAF – Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean. https://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/2430

Andean Development Corporation (CAF). (2025, April 28). Canelones Public Space Improvement Program (CFA012132). https://www.caf.com/en/who-we-are/projects/cfa012132-canelones-public-s…

Angel, S., Blei, A. M., Parent, J., Lamson-Hall, P., & Galarza Sanchez, N. (2016). Atlas of urban expansion: The 2016 edition. Volume 1: Areas and densities. New York University; UN-Habitat; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Birch, E., & Wachter, S. (Eds.). (2011). Global urbanization. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bloomberg.com. (2024, May 2). Buenos Aires officials to meet investors as city weighs global bond sale. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-02/buenos-aires-city-to…

Bloomberg Philanthropies. (2024, July 20). COP28 Local Climate Action Summit. https://www.bloomberg.org/cop28-local-climate-action-summit/

Bocarejo, J. P. (2020). Congestion in Latin American cities: Innovative approaches for a critical issue. International Transport Forum Discussion Papers, No. 2020/28. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2020/09/c…

Cardano-UK. (2021, April 6). GuarantCo: ‘Doing our best to make ourselves superfluous’. https://www.cardano.co.uk/industry-insights/guarantco-doing-our-best-to…

Caselli, S., Corbetta, G., Cucinelli, D., & Rossolini, M. (2021). A survival analysis of public guaranteed loans: Does financial intermediary matter? Journal of Financial Stability, 54, Article 100880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2021.100880

Castillo, E., & Cabral, R. (2024). Subnational public debt sustainability in Mexico: Is the new fiscal rule working? European Journal of Political Economy, 82, Article 102512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2024.102512

Centro de Economía Política Argentina (CEPA). (2025, February 3). Transfers to provinces from national tax resources and co-participation transfers: Data as of January 2025. https://centrocepa.com.ar/images/2025/02/2025.02.03%20-%20Transferencia…

City Climate Finance Gap Fund. (2023, October 30). Increasing support for resilient, low-carbon urban development. https://www.citygapfund.org/news/increasing-support-resilient-low-carbon-urban-development

Cities Climate Finance Leadership Alliance (CCFLA), & Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Commission. (2025). Integrating urban and subnational priorities into country platforms: Policy brief. https://citiesclimatefinance.org/publications/integrating-urban-and-subnational-priorities-into-country-platforms

Cleary Gottlieb. (2023, December 28). The Municipality of Lima’s bond offering. https://www.clearygottlieb.com/news-and-insights/news-listing/the-munic…

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). (n.d.). Internal and external public debt. Plataforma Urbana y de Ciudades. https://plataformaurbana.cepal.org/es/instrumentos/financiamiento/deuda…

Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). (2023). Global landscape of climate finance 2023. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of…

Daunt, A., & Siedentop, S. (2025). Unravelling urban typologies in Latin American cities: Integrating socioeconomic factors and urban configurations across scales. Applied Geography, 174, Article 103460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2024.103460

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). (n.d.-a). CEPALStat: Statistics and indicators. https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/dashboard.html?theme=1&la…

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). (n.d.-b). Economía urbana y finanzas municipales. Plataforma Urbana y de Ciudades. https://plataformaurbana.cepal.org/es/action-areas/economia-urbana-y-fi…

Economist Impact. (2024). Infrascope 2023/24: Evaluating the environment for public-private partnerships in Latin America and the Caribbean. Economist Impact. https://impact.economist.com/new-globalisation/infrascope-2024/download…

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). (2025). A look back: EBRD Green Cities in 2024. https://www.ebrdgreencities.com/news-and-events/news/a-look-back-ebrd-g…

European Commission. (2024). European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus. https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/funding-and-technical-a…

European Commission. (2023). InvestEU Green Cities Framework. https://investeu.europa.eu/investeu-operations-0/investeu-operations-list/investeu-green-cities-framework_en

European Investment Bank. (2023a). Joint report on multilateral development banks’ climate finance. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/3258e1d4c1e84fd961b79fe54e7df85c-0…

European Investment Bank. (2023b). Default statistics: Private and sub-sovereign lending 1994–2023. https://www.africainvestor.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/private_and_s…

Falduto, C., Noels, J., & Jaschik, R. (2024). The new collective quantified goal on climate finance: Options for reflecting the role of different sources, actors, and qualitative considerations (OECD/IEA Climate Change Expert Group Papers No. 2024/02). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/7b28309b-en

Ferreira, F., Messina, J., Rigolini, J., López-Calva, L., Lugo, M., & Vakis, R. (2013). Economic mobility and the rise of the Latin American middle class. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/45f7c3c0…

Fitch Ratings. (2023, May 17). Fitch affirms Barranquilla’s IDRs at ‘BB’; Outlook stable. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/international-public-finance/fitc…

Garbacz, W., Vilalta, D., & Moller, L. (2021). The role of guarantees in blended finance (OECD Development Cooperation Working Papers, No. 97). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/the-role-of-guarantees-in-blended-…

Green Climate Fund (GCF). (2022). Funding proposal, FP197: Green Guarantee Company. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/funding-prop…

Green Finance LAC. (2023, January 4). Municipality of Godoy Cruz will issue green bonds to finance solar energy. https://greenfinancelac.org/resources/news/municipality-of-godoy-cruz-w…

Government of the City of Buenos Aires. (2024, September 12). Fitch international rating report communication. https://buenosaires.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2024-09/ComunicadoFitchR…

GuarantCo. (2019, March). Ho Chi Minh Infrastructure Investments JSC. https://guarantco.com/our-portfolio/ho-chi-minh-infrastructure-investments-jsc/

GuarantCo. (2023, November 23). Lagos Free Zone Company. https://guarantco.com/our-portfolio/lagos-free-zone-company/

Guterres, A. (2019). Urban infrastructure choices will have ‘decisive influence on the emissions curve’. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/news/guterres-urban-infrastructure-choices-will-have…

Hallegatte, S., Rentschler, J., & Rozenberg, J. (2019). Lifelines: The resilient infrastructure opportunity. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31805

IDB Invest. (2022, November 29). IDB Group supports BICE to issue the first sustainable bond in Argentina. https://idbinvest.org/en/news-media/idb-group-supports-bice-issue-first…

International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2024, May). Emerging market green bonds. https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2024/emerging-market-green-bond…

Inter-American Development Bank. (2018). Next steps for decentralization and subnational governments in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://publications.iadb.org/en/publications/english/viewer/Next-Steps…

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025, February). Electricity 2025: Analysis and forecast to 2027. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/0f028d5f-26b1-47ca-ad2a-5ca310…

Kemp, J. (2024, September 25). Central and South America drought and hydro power. https://jkempenergy.com/2024/09/25/south-americas-electricity-grids-und…

Lima, R., Callado, S., Lima, A., & Santos, R. (2020). Dependência municipal das transferências intergovernamentais e desenvolvimento socioeconômico: Uma análise dos municípios da região da Grande Fortaleza – Ceará. Revista CEJUR, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.21902/rctjsc.v8i1.349

Lozano, I., & Julio, J. (2016). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in Colombia: Evidence from regional-level panel data. CEPAL Review. https://doi.org/10.18356/d80b22b8-en

Maloney, W., Garriga, P., Meléndez, M., Morales, R., Jooste, C., Sampi, J., Thompson Araujo, J., & Vostroknutova, E. (2024). Competition: The missing ingredient for growth? Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Review. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/lac/publication/perspectivas-econom…

Mangones, S. C., Cuéllar-Álvarez, Y., Rojas-Roa, N. Y., & Osses, M. (2025). Addressing urban transport-related air pollution in Latin America: Insights and policy directions. Latin American Transport Studies, 3, Article 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.latran.2025.100033

Marks, G. (2021). Regional Authority Index scores for 2018 [Data set]. European University Institute. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/70298

Marsh, W. B., & Sharma, P. (2024). Loan guarantees in a crisis: An antidote to a credit crunch? Journal of Financial Stability, 72, Article 101244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2024.101244

Meridiam. (n.d.). Sustainable and resilient cities of tomorrow. https://www.meridiam.com/assets/sustainable-and-resilient-cities-of-tom…

Moody’s Investors Service. (n.d.). Moody’s research and ratings: Argentina. Moody’s Investors Service. https://www.moodys.com/researchandratings/region/latin-america-caribbea…

Morales, S. (2023, May 26). Analyzing segregation of informal residents in Latin American cities’ periphery using remote sensing. Revista Cartográfica. https://doi.org/10.35424/rcarto.i106.2667

Ocampo, Ó. (2025, April). The Mexican federalism, municipalities, and property tax. Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (IMCO). https://imco.org.mx/el-federalismo-mexicano-el-municipio-y-el-predial/

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2024a). Climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries in 2013–2022. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/climate-finance-provided-and-…

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2023). Financing cities of tomorrow: G20/OECD report for the G20 Infrastructure Working Group under the Indian Presidency. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/financing-cities-of-tomorrow_51bd124a-en

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2024b). Infrastructure for a climate-resilient future. https://doi.org/10.1787/a74a45b0-en

OECD-UCLG World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment. (2024). Subnational government finance and investment data. https://stats.oecd.org/viewhtml.aspx?datasetcode=SNGF_WO&vh=0000&vf=00&…

Pasternack, S. (2011). Thinking about urban services needs in fast-growing cities: Housing in São Paulo. In E. Birch & S. Wachter (Eds.), Global urbanization (pp. xx–xx). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Plataforma Urbana y de Ciudades. (2024, July 20). Deuda pública interna y externa. https://plataformaurbana.cepal.org/es/instrumentos/financiamiento/deuda…

Quiroga, C. J., & Smith, H. (2019). Fiscal sustainability of Mexican debt decisions: Is bad behavior rewarded? https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/events/files/jimenez_smith_1_…

Ricciulli-Marín, D., Bonet-Morón, J., & Pérez-Valbuena, G. (2022, December). Cien años de finanzas públicas territoriales en Colombia. Banco de la República. https://pruebas.repositorio.banrep.gov.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/b9…

Rodriguez, E., & Yoon, J. (2024, May 8). Rolling blackouts hit several cities as heatwave scorches Mexico. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/08/world/americas/mexico-blackout-heat-…

Samujh, R., Twiname, L., & Reutemann, J. (2012, December 31). Credit guarantee schemes supporting small enterprise development: A review. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting, 5(2). https://mojem.um.edu.my/index.php/AJBA/article/view/2658

S&P Global Ratings. (2025, February 6). Five Argentine subnational governments upgraded to 'B-' from 'CCC. https://disclosure.spglobal.com/ratings/en/regulatory/article/-/view/ty…

Sigrist, S., & Toro Botero, A. (2017). Three ways to partner with cities and municipalities to mobilize private capital for infrastructure: A look at Latin America. Public-Private Partnership Resource Center (PPPRC), World Bank Group. https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/subnational-and-municipal/three-ways-partner-cities-and-municipalities-mobilize-private-capital-infrastructure-look-latin-america

Statista. (2025). Most populated metropolitan areas in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2025. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1374285/largest-metropolitan-areas-…

Tesouro Nacional. (2025). Transfers to states and municipalities. Tesouro Transparente. https://www.tesourotransparente.gov.br/temas/estados-e-municipios/trans…

TRYSM. (2022, October 31). Municipality of Córdoba’s green and infrastructure bond issuance for AR$ 2,846,069,500. https://www.trsym.com/municipality-of-cordobas-green-and-infrastucture-…

UNCDF. (2022, December 18). European Union greenlights UNCDF guarantee facility for cities amounting to EUR 154 million. https://www.uncdf.org/article/8078/european-union-greenlights-uncdf-gua…

United Nations Human Settlements Programme. (2024). Urban climate action: The urban content of the NDCs – Global review 2022. https://doi.org/10.18356/9789213589366

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1

U.S. Department of State. (2025). Cities Forward: Green City Finance Guide – Latin America and the Caribbean. https://www.state.gov/cities-forward-green-city-finance-guide-latin-ame…

World Bank Group. (2023). Annual report MIGA. https://www.miga.org/2023-annual-report

World Bank Group. (n.d.-a). A roadmap for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean 2021–2025. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d3e9d5ba…

World Bank Group. (2020). Building sustainable and resilient infrastructure in Latin American cities: The role of public-private partnerships (Infrastructure Notes, No. 34). https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34080

World Bank Group. (n.d.-b). City creditworthiness initiative: A partnership to deliver municipal finance. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/brief/city-creditwo…

World Bank Group. (2023, January 24). MIGA project portfolio. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0042300

World Bank Group. (2021). The gradual rise and rapid decline of the middle class in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/831061624545611093/pdf/The-…

World Bank Group. (2025). Unlocking subnational finance: Overcoming barriers to finance for municipalities in low- and middle-income countries. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/91308584-2eab-…

World Bank Group. (2024, July 1). World Bank Group guarantee platform goes live. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/07/01/world-bank-g…

World Economic Forum. (2018, June). Latin America’s cities are ready to take off. But their infrastructure is failing them. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/06/latin-america-cities-urbanizatio…

World Resources Institute (WRI). (2023). Coalition for High Ambition Multilevel Partnerships (CHAMP). https://www.wri.org/initiatives/coalition-high-ambition-multilevel-part…

Yao, N., Ebeke, C., Florence, J., Medici, A., Panton, A., Mendes, M., & Tavares, B. (2023, September 21). Structural reforms to accelerate growth, ease policy trade-offs, and support the green transition in emerging market and developing economies. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2023/…