When Sarah Lerner showed up at the Eastern State Penitentiary on a dark, cold January morning for the first day of David Brownlee’s class about the historic prison-turned-museum in Philadelphia’s Fairmount neighborhood, she wasn’t signed up for the class, or even planning on taking it.

“I just tagged along with friends to check it out,” says Lerner, a first year graduate student in historic preservation. “But it was so immers ive from the second I got there. I was hooked.”

ive from the second I got there. I was hooked.”

The seminar, held at Eastern State in the spring of 2019, was designed and led by Art History Professor and Penn IUR Faculty Fellow David Brownlee, as part of the Humanities+Urbanism+Design Initiative (H+U+D), a collaborative project of the Penn Institute for Urban Research and the Stuart Weitzman School of Design. H+U+D, supported by a five-year $1.533 million grant from the Mellon Foundation, aims to bring together parts of the university around the idea of the inclusive city. In addition to research, colloquium and events, the initiative sponsors several city-focused seminars each year. This spring, H+U+D offered it’s first “anchor institution seminar”; it focused on the history and management of Philadelphia’s famous Eastern State Penitentiary.

Taught in partnership with staff at Eastern State—namely, Sally Elk, President and CEO, and Sean Kelley, Senior Vice President and Director of Interpretation— the Eastern State seminar included 15 undergraduate and graduate students from Penn’s School of Arts and Sciences and Weitzman School, and explored a range of topics about the site’s management and mission, including strategic planning, interpretation of the site, program design, architectural planning and conservation, fund raising, and engagement with diverse constituencies and neighborhoods.

According to Lerner, housing the class in the building served as a constant reminder of the site’s history, mission, and power. “Every day, to get to th e classroom, we walked through the entire building, with its crumbling cell blocks and grand architecture,” she says. “You could see the layers of history just by being in that space.”

e classroom, we walked through the entire building, with its crumbling cell blocks and grand architecture,” she says. “You could see the layers of history just by being in that space.”

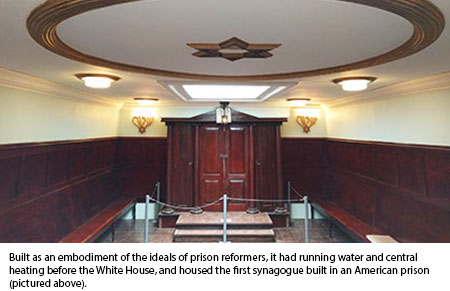

Those layers of history date back to 1822, when construction began on Eastern State, the world’s first true “penitentiary,” an architectural wonder designed to inspire penitence in the hearts of its prisoners. (Famous prisoners included crime boss Al “Scarface” Capone and serial bank robber William “Slick Willie” Sutton.) Built as an embodiment of the ideals of prison reformers, it had running water and central heating before the White House, and housed the first synagogue built in an American prison.

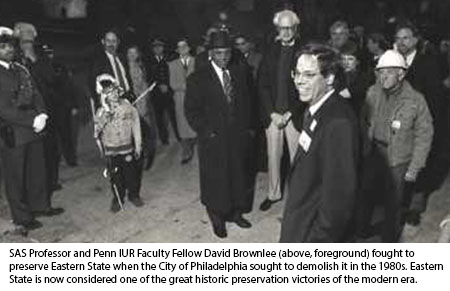

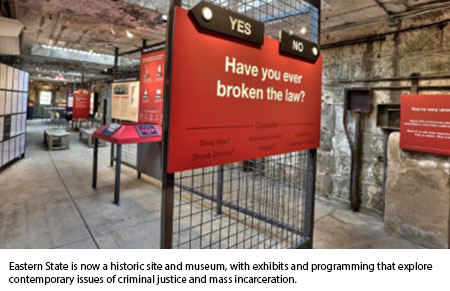

One of the most famous buildings in Philadelphia, and now a National Historic Landmark, Eastern State ceased housing prisoners in 1971, and was slated to be demolished by the City of Philadelphia in the 1980s. After a group of volunteer advocates, including Brownlee, fought to preserve the site, the City agreed to save it. C onsidered one of the great historic preservation victories of the modern era, Eastern State is now a historic site and museum, with programming that explores contemporary issues of mass incarceration and criminal justice—subjects that many Americans believe to be the most pressing civil rights issues of our times.

onsidered one of the great historic preservation victories of the modern era, Eastern State is now a historic site and museum, with programming that explores contemporary issues of mass incarceration and criminal justice—subjects that many Americans believe to be the most pressing civil rights issues of our times.

According to Brownlee, the course was designed to explore these contemporary issues of mass incarceration and criminal justice from a real-world, interdisciplinary perspective.

"I wanted students to come away from this class with a sense that they had actually put their academic training to work in the real world,” says Brownlee. “I wanted them to see the way research and study can be activated in public-facing institutions. The students in this class come from many walks of life and have diverse academic interests. I think each student found something in this class related to their specific interests, but they also came to understand that all of their interests converge in one place. The interdisciplinary really blossoms here."

As part of this interdisciplinary focus, students were asked to undertake final projects that explored topics of their own choosing related to the site. Research topics included everything from religion and public health in prison to the role of baseball at Eastern State.

Lerner, for her part, undertook a final project on the history of clothing at Eastern State. She worked with the archivist and head of research at the Penitentiary to unearth the history of prison clothing at the site; she also interviewed formerly incarcerated women about how they used clothing to express themselves while incarcerated. In the end, Lerner created a proposed exhibit about the history of prison clothing and  how it has influenced historical and modern fashion trends and pop culture.

how it has influenced historical and modern fashion trends and pop culture.

Using the history of Eastern State as a way to explore and address contemporary issues related to incarceration is exactly what Brownlee hopes his students have taken away from the course.

"I went into teaching because I wanted to change the world,” says Brownlee. “I thought the project of teaching people to use their brains rather than fists to solve problems was a good idea. This class is a project of historic preservation and activating and using this preserved building as a place where we can educate people and make the world better."

Lerner, for one, seems to be embodying Brownlee’s hopes. She is planning on continuing to study issues of incarceration, and is taking a Women’s Studies class next semester on health education for incarcerated women. She hopes that her final research project about the clothing of incarcerated women can one day be part of Eastern State’s public exhibition.

“Although Eastern State looks like a ruin—like it could be from hundreds of years ago—the prison closed just 40 years ago,” says Lerner. “And prisons that have just closed last year look like this too. The class really opened up the human element of prisons and the necessity to involve those who have been incarcerated as stakeholders in this important story.”

“Eastern State is always presented as a prime example of how historic buildings can be preserved and used to educate,” she says. “What I appreciated about the class is that it forced us to think of Eastern State not just as a museum but as a place people actually lived. It hit me: Wow, this isn’t just a historic place. This is a reality.”