Edward Glaeser is the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics at Harvard, where he also serves as Director of the Taubman Center for State and Local Government and the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston. The following article is adapted from “The Historical Vitality of Cities” Glaeser’s chapter in “Revitalizing American Cities” (Penn Press 2014), edited by Susan Wachter and Kimberly Zeuli. To read more about the book Revitalizing American Cities or to order your copy, visit the Penn Press website.

Cities are, fundamentally, the people within them. It is people who envision and implement change. Thus, the route to urban vitality lies in adopting policies that help people to thrive and to innovate; in other words, the route to revitalization lies in promoting human capital. While the federal government has a role to play in this, local governments play the biggest role in bringing people together in cities.

What should cities do to attract human capital? To retain and attract jobs and residents, in short, to make cities livable, there is no substitute for providing the basics of city government. Since the dawn of history, cities have been dealing with the demons that come with density. If two people are close enough to give each other an idea face to face, they are also close enough to give each other a contagious disease, and, if two people are close enough to buy and sell a newspaper, they are close enough to rob each other (Glaeser and Sacerdote 1999). The research demonstrates the importance of government provision of public safety as a basic urban good in order to retain and attract new residents (Gould Ellen and O’Reagan 2009).

Public safety, in the broadest sense, including public health, is historically a key factor in urban growth. Historically, the most important job of city government has been to provide clean water. Remarkably, cities that were once dreadful have become quite pleasurable, something that happened only through massive investments by local government to provide fundamental urban services such as water and sanitation. In 1900, the life expectancy for a boy born in New York City was seven years less than the national average; today, life expectancies in New York are more than two years above the national average (Glaeser 2011).

The relative safety of cities did not happen easily. Cities and towns were spending as much on clean water at the start of the twentieth century as the federal government was spending on everything except the post office and the army. Cities and towns historically played an essential role in creating safe cities, and local government continues to be the place to be for those who care about improving the lives of ordinary people.

Beyond the provision of basics including public safety, what should be done about decline? I will discuss four different approaches: the physical capital approach, the tax incentive approach, the shrinking to greatness approach, and the human capital approach.

Physical Capital Investments

Do infrastructure investments make a difference—can we change the tides of history with major infrastructure investments? Do they meaningfully help local residents? Do they meet cost-benefit analysis? I believe the federal government is playing too great a role in financing local infrastructure and is, essentially, pretending that cities are structures rather than people. This has proven to be a curse for our urban areas. However, the federal government does have an infrastructure role to play toward cities, in helping cities care for people with fewer resources.

Urban poverty is rarely a sign that cities are making mistakes. Rather, cities attract poor people with a promise of economic opportunity, a more humane social safety net, and the ability to get around without a car. If you build a new subway line, you find that poverty rates go up around subway stops (Glaeser, Kahn, and Rappaport 2008). Is the subway line impoverishing its neighbors? No, the subway is doing exactly what it should: providing a means of getting around for those Americans who cannot afford a car for every adult.

But caring for the less advantaged is a role for the federal government—not for localities. When a local welfare state is created, the rich move out, leaving pockets of poverty. In the 1960s, city after city faced social distress; oft en, they tried to handle the distress locally, but the firms and the wealthy left, leaving behind an urban crisis.

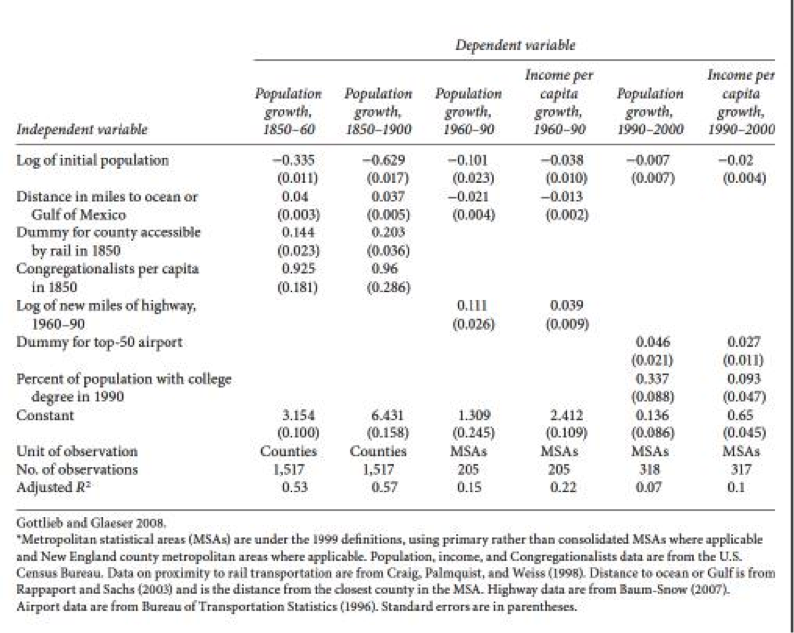

After the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1973, the federal government funded transportation infrastructure. But Detroit, like other struggling cities, did not need transportation infrastructure; it needed investment in children, safety, and schools. The table below shows that the transportation infrastructure investments had relatively little impact on urban growth in the following decades (Gottlieb and Glaeser 2008).

Historical Regressions of Population and Income Growth on Metropolitan-Area Transportation Measures and Controls*

Tax Incentives

Tax incentives do seem to make a difference. Busso and Kline (2008) find 2 to 4 percent increases in employment rates in empowerment zones, while Greenstone and Moretti (2004) find significant impact in luring million-dollar plants.

The work suggests that keeping tax rates as low as possible is appropriate. But are these results applicable to cities? Greenstone and Morretti’s results (2004) focus mostly on gains in America’s rural areas, as these areas are actually winning battles for million-dollar industrial plants. Rural areas may indeed have a comparative advantage in old-style industry or manufacturing; these activities left our cities decades ago. It is very hard to imagine that cities have a comparative advantage in this arena relative to an arts scene, to an ideas economy, to creativity, to the things that actually take advantage of the proximity of people that enables the spread of ideas. Nonetheless, tax policy in general does matter, as do federal policies that support the poor and vulnerable, who are concentrated in cities, and that counteract the associated heavy fiscal burden on cities.

Shrinking to Greatness

For some cities, the best course may not be returning to a former state by growing back their population to 1950s levels. Instead, cities like Cleveland, Detroit, Saint Louis, or Youngstown have started to embrace the vision of “shrinking to greatness.” The governments and populations of these localities recognize that their housing stock and their public infrastructures cannot be sustained with their current population and economic activity and that they are not going to get back the population level that requires such infrastructures. The concept of shrinking to greatness is to shrink the physical footprint of the area to reduce the costs of city services and potentially produce more usable land. Recognizing that people will not come back to repopulate once-dense neighborhoods, cities that adopt this approach develop plans to destroy empty and often unsound homes and replace them with parks, open space that is less costly to maintain and does not pose hazards. While this approach does not immediately bring back economic activity and people, it can make these cities more attractive and less costly to maintain. This approach is difficult, and significant opposition exists to any plans that displace residents. Nonetheless, some city leaders, including mayors David Bing in Detroit and Dayne Walling in Flint, have made a commitment to do some targeted demolition and have allocated funds and made use of eminent domain to do so.

Accepting that sustainability entails downsizing their physical footprints, sharing or consolidating urban services between adjacent communities, and concentrating redevelopment efforts on the remaining core of density and activity will not bring cities back to their former states but will make them more efficient in delivering services and better able to provide a good quality environment for their residents (Glaeser 2011).

Human Capital

The most difficult and promising approach is to focus directly on human capital: on attracting, retaining, and empowering skilled people. This is not just about appealing to twenty-seven-year-old poets and artists; it is also about appealing to thirty-eight-year-old moms who work in research labs and care about the safety, education, and commutes of their children. We cannot ignore the basics of city government and get sidetracked by the idea of glitzing our way to successful redevelopment. Fundamentally, attracting and retaining smart people means providing basic city government services well.

That, of course, also requires innovation directly in education. The challenge of providing better schooling, for example, requires innovative models and the development of a better understanding of how to deliver education in an urban environment that counteracts the differential that exists today in educational outcomes in cities versus suburbs (Jacob and Ludwig 2011). The success of older cities in reinventing themselves lies in their capacity to develop their human capital through education and prepare a skilled workforce that will be able to demonstrate the creativity required by the knowledge economy.

* * *

America’s cities continue to face challenges. But the ability of our nation and our species to endure and innovate because we are connected by our cities, because we are more than the sum of our parts, because we learn from the people around us, because we innovate in the urban milieu—that track record is remarkable and it will continue.