What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia?

This is the central question that both underscores and propels Monument Lab: A Public Art and History Project. The project, which began five years ago as a conversation between historian and curator Paul Farber and me, has grown from a discussion about the power that monuments have in shaping historical narratives into a large-scale public installation of 20 “prototype monuments” across the city of Philadelphia. On display from September 16 to November 19, each prototype monument responds to this central question as part of a dialogue about history, memory, and the City’s collective future.

Monument Lab’s first iteration, in 2015, was an installation in Philadelphia’s City Hall square that featured a large outdoor classroom designed by the late Penn Professor Terry Adkins after a drawing by 18th century educator Joseph Lancaster, and invited citizens to reflect upon the project’s central question: What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia? This year’s project, produced in collaboration with Mural Arts Philadelphia, the nation’s largest public arts program, is an expansion and elaboration on the 2015 installation. For the current Monument Lab 20 artists or artist teams produced temporary prototype monuments across 10 sites in Philadelphia’s iconic public squares and neighborhood parks. They present these site-specific, socially-engaged artworks together with research labs where they [or that] collect creative monument proposals from Philadelphians and visitors.

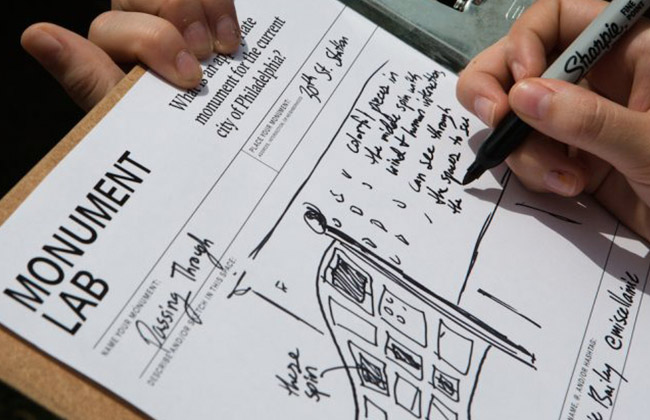

At the research labs that accompany each prototype, researchers ask members of the public to propose an appropriate monument for Philadelphia today. (Photo credit: Steve Weinik, Monument Lab, Mural Arts)

At the research labs that accompany each prototype, researchers ask members of the public to propose an appropriate monument for Philadelphia today. At the time of this writing, with the exhibition not quite a third of the way through, we have received well over 2,000 proposals from respondents ranging in age from 3 to 91. We will meld the proposals into a dataset of public input and present it in a final report to the city. During the exhibition, a constantly updated dataset of the public input is on view at the Morris Gallery at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Paul and I began this project hoping to understand better the mechanisms of memorialization, particularly by questioning the status of the monument and how we might challenge a monument’s canonical character. We were also interested in unacknowledged histories that now have become evacuated from the monument landscape, yet remain palpable in their absence. Philadelphia’s extant memorial landscape is identified with the statues of the dominant citizen class and by the nearly total absence of officially sanctioned statuary of historical African-Americans and women. After all, Philadelphia unveiled the first memorial to an African American on public ground in September of 2017, a statue of the great nineteenth-century civil rights advocate and educator, Octavius Catto.

“If They Should Ask” by Sharon Hayes in Rittenhouse Square. (Photo credit: Steve Weinik, Monument Lab/Mural Arts Program)

African Americans make up over 40 percent of the citywide population and the story of African American struggles and contributions are central to any appreciation of Philadelphia’s history and distinction. Artist and University of Pennsylvania Professor Sharon Hayes’ contribution to Monument Lab, titled If They Should Ask, takes the form of a collection of empty plinths inscribed with the names of important Philadelphian women deserving of a statue. Presently, there are only two full figure historical women figures represented within the inventory of Philadelphia statuary, Joan of Arc and Mary Dyer, a colonial-era advocate for First Amendment rights, both important and tragic figures but neither with any affiliation with Philadelphia.

Given this vacuum, we aimed to create an exhibition that would embody democracy through the participation of a wide and varied audience, engaged in public dialogue. We wanted to listen to all Philadelphians from throughout their city, and give voice to those citizens who too often go unheard.

With this in mind, we erected and programmed Monument Lab stations in several sites beyond Center City, including Norris Square, Malcolm X Park, Marconi Plaza, Fairhill, Penn Treaty Park, the intersection of Belmont and Parkside in West Philadelphia, and Vernon Park. Karyn Olivier, an artist whose remarkable prototype sculpture entitled The Battle is Joined is sited in Germantown’s Vernon Park, has noted the local residents’ surprise and delight that an important art project would be installed in their neighbourhood, which is largely devoid of public art.

“The Times” by Tyree Guyton at A Street and East Indiana Avenue. (Photo credit: Steve Weinik, Monument Lab/Mural Arts Program)

In Fairhill, at the intersection of Indiana Avenue and A Street, Tyree Guyton, an artist from Detroit and progenitor of The Heidelberg Project, produced a work titled The Times. He imbued the piece with a political protest against poverty and the abandonment of the civic body, the social spaces comprising the civic realm. The Times is a work of community participation that features community-painted images of giant clocks affixed to the facade of a block-long empty and bricked warehouse. Each of the clocks denotes a different time but together they exist synchronically. Guyton has stated of this work:

Plato said, ‘Time is the moving image of reality.’ What this means to me is that everything we do revolves around time and yet the only time that we ever really have is the very moment we are in. My challenge with this project [The Times] is to help people to appreciate the present time as a time to act, think, be and do, here and now. Yesterday lives only in our minds, and tomorrow is not promised. I believe that we must make the most of time, and the time to do that is now.

To visit Guyton’s work is to commit to visiting a distressed neighbourhood beset by poverty and its associated problems. But it is also a neighbourhood of Philadelphians whose voices need to be heard.

To take in Monument Lab is to traverse and be present physically across every precinct of Philadelphia. We wanted Monument Lab to prompt the public to identify with Baudelaire’s figure of the flaneur in The Painter of Modern Life (1863). We want Philadelphians to “rush into the crowd in search of a man unknown to him” and to throw “away the value and the privileges afforded by circumstance.” We wanted Philadelphians to visit places within their own city that they had never before visited, if only to experience anew their city through the lives of others.

The message of Monument Lab is that the city is a place of limitless possibility, and that in reflecting on this city, we can begin to understand the power of being a human among other humans. The city is itself a living monument to humanity, with all its potential and all its challenges. Monument Lab aims to unearth potential solutions to a better collective future for Philadelphia, but such solutions can only come about if we recognize that our departure point must be from the view that the city is a place of many voices, which deserve to be heard.

Ken Lum is Penn IUR Faculty Fellow and Professor and Chair of the Fine Arts Department at the University of Pennsylvania.