Key Message

The Penn IUR Recovering Cities Project highlights the varied and evolving impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on New York City. The city faced significant challenges, including a severe public health crisis, economic downturns, increased unemployment, and rising crime rates. However, efforts to recover have been marked by resilience and adaptability. Key sectors such as real estate, tourism, arts, and entertainment have shown signs of recovery, though full recovery is anticipated to take several years.

The report discusses the importance of adaptive strategies and collaborative efforts in addressing the pandemic's long-term impacts. Continued focus on public health measures, economic support, and community resilience will be crucial for New York City's recovery. The city must navigate ongoing uncertainties, including potential new variants and fiscal challenges, to ensure a sustainable and inclusive recovery. The collective efforts of city leaders, businesses, and residents will be pivotal in shaping New York City's post-pandemic future.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered unprecedented disruption in cities around the world. Beyond the tremendous suffering it caused to individual households through loss of life and income, it also brought cities to a virtual standstill. Cities had never experienced anything like this in recent history, even during natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and economic recessions. New York City was an early epicenter of the crisis within the United States. As intensive care units filled with critically ill patients, offices, businesses, and schools shut down and subway stations and airports were deserted. Those who could, left the city indefinitely.

In parallel, civic organizations, think tanks, and universities began monitoring the impacts of the crisis on the city, and exploring what it would take to help it recover. In September 2020, Penn Institute for Urban Research (Penn IUR) launched its “Recovering Cities Project,” an initiative to track the recovery of a major U.S. city from the pandemic and its economic impact. It focuses on New York City, a world city of global economic and cultural importance. The project involves regular data gathering on the state of the city as well as the convening of bimonthly discussion groups, in which civic, academic, professional, and industry leaders observe and discuss responses to recent challenges: pandemic-related public health concerns, economic decline, and the associated exacerbation of racial and other inequalities.

The group includes more than a dozen leaders from the private and nonprofit sectors with deep roots in the city and expertise in education, real estate, regional planning, technology, tourism, and other fields. They convened their first meeting on September 17, 2020, and have met every two months since then, via Zoom. William Lukashok, Director of Capital Markets, Prana Investments and a member of the board of Penn IUR, chairs the meetings. He begins the meetings by presenting a data “dashboard,” prepared by Penn IUR, which includes various metrics related to the state of the city’s recovery. The following discussions, often featuring guest speakers, contribute texture via qualitative observations that help explain or illustrate the metrics.

This report summarizes the results of the first year’s meetings, identifying the key trends and themes that have emerged since the start of the project. It has three parts. The first part presents the health conditions during the course of the project. The second part covers the changing health and socioeconomic conditions and the group’s perceptions about the timing of the recovery over the twelve months of the project. The third part takes stock of the group’s continuing concerns for the future.

The Backdrop

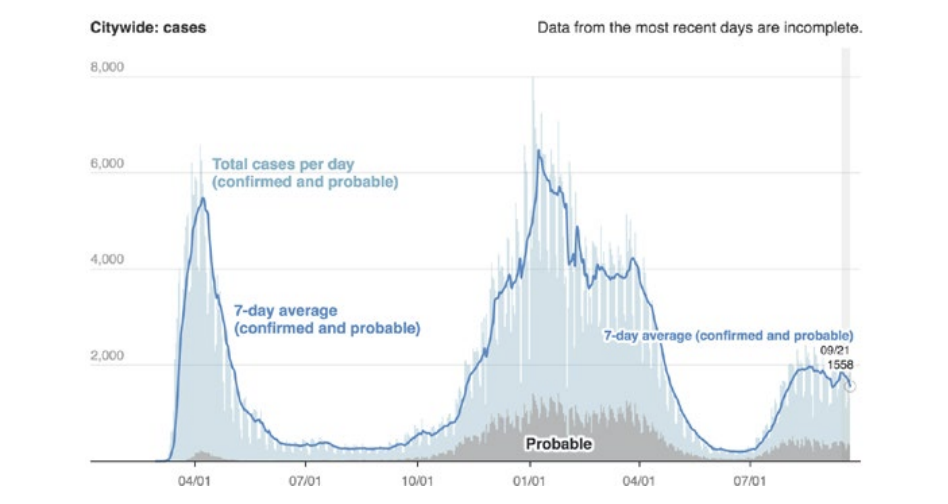

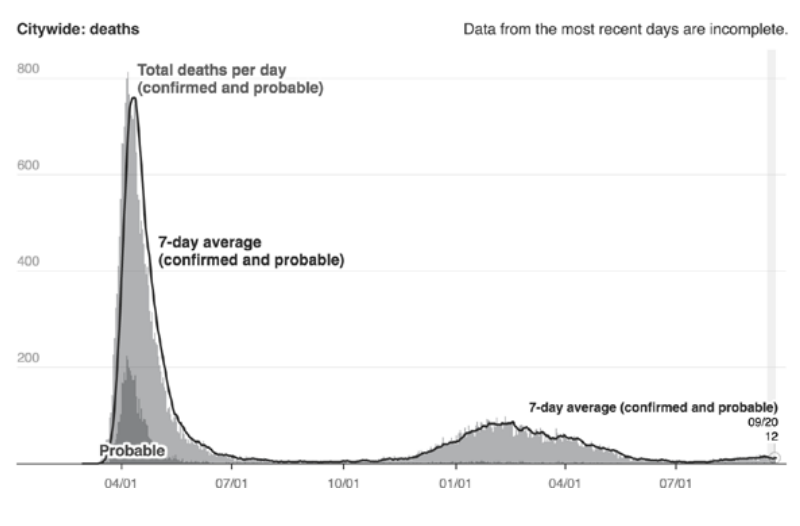

Starting in March 2020, the public health efforts focused on the fight against the virus itself, although, as the pandemic appeared to abate in the summer, these efforts relaxed a bit only to intensify when the Delta variant entered the picture. In April 2020, the first wave of infections in New York City peaked: the city recorded more than 5,000 new cases and 500 deaths daily. At that time, 90 percent of the city’s ICU beds were in use. The city’s Hispanic and Black populations were getting sick and dying at much higher rates than the white population, a disparity that was also observed nationally. By September, when the Recovering Cities project began, the rates had declined to 200 cases per day (Figure 1) and daily deaths were in the single digits (Figure 2). However, as the group met, cases peaked in the winter months in 2021, subsided by the end of June, and rose again in July and August. With the vaccination rate rising, all had looked good for a September return to normal as most observers anticipated. While the surprising emergence of the Delta variant slowed the recovery neither the cases nor the deaths reached the earlier peaks. In late September 2021, cases showed signs of subsiding, likely due to the high levels of vaccination achieved among the city’s adult population.

When the case and death rates started to drop during the summer of 2020, the economic, social, and fiscal impacts of the crisis on the city moderated in some sectors but accelerated in others. Unemployment, which had risen to 20 percent in May, began to recover, slowly and unevenly. In September 2021, it was 11 percent, higher than the national rate that hovered around 5 percent.

Figure 1: New York City COVID-19 cases over time (Source: NYC Dept. of Health)

Figure 2: New York City COVID-19 deaths over time (Source: NYC Dept. of Health)

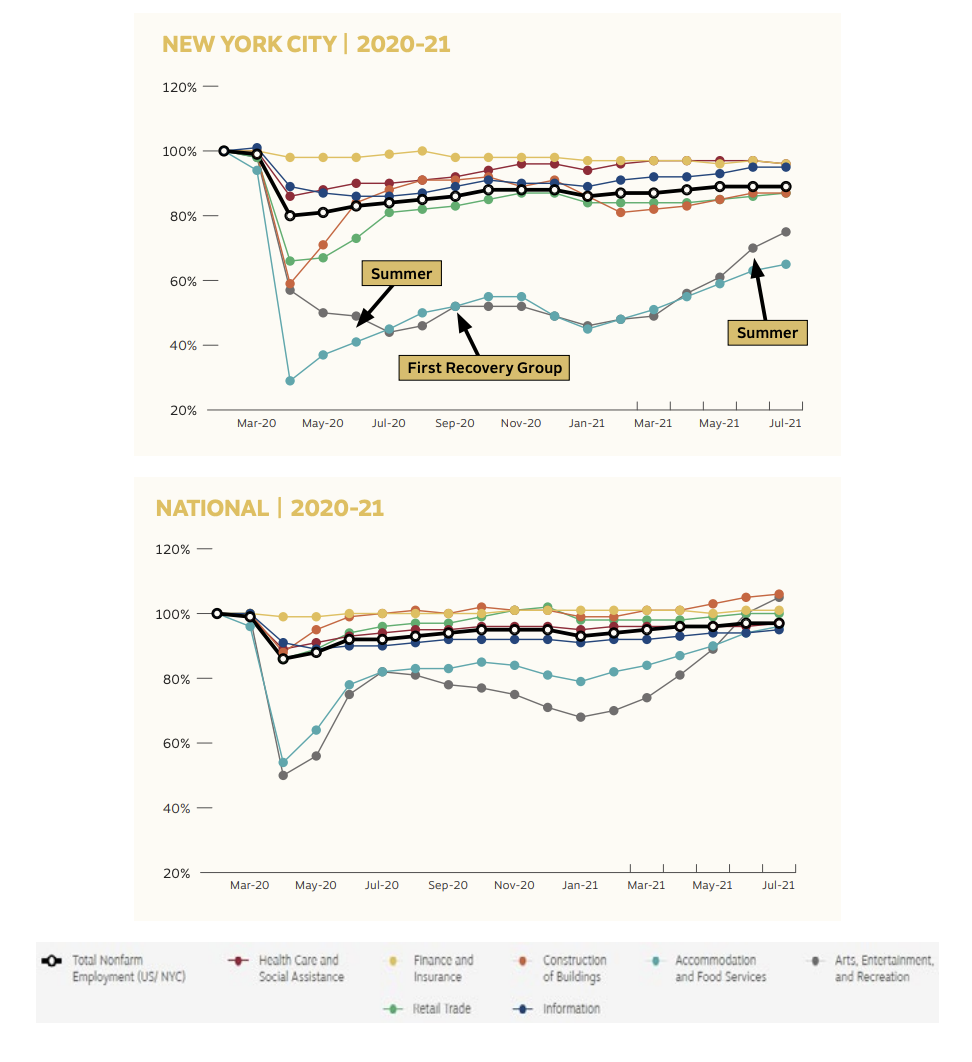

Figure 3: Employment in selected industries as a percentage of February 2020 employment, New York City (top) and U.S. (bottom) (Source: Penn IUR Recovering Cities Dashboard, September 2021.)

The summer of 2020 also saw a spike in crime. For example, shooting incidents in August were double those at the same month the previous year. However, by 2021, as will be discussed later, these rates were abating but did not decline to their prepandemic levels.

Figure 3 shows employment in selected industries as a percentage of February 2020 employment in New York City (top) and the nation (bottom). Hardly any jobs were lost in some industries, like finance and information technology. A large share of retail and construction jobs were lost at the start of the pandemic, but these industries recovered somewhat over the summer of 2020. By contrast, employment in the city’s arts, entertainment, and recreation industries was cut in half at the start of the pandemic and remained at reduced levels a year later, slowly improving in summer 2021. The accommodation and food services lost more than two out of three jobs at the beginning of the pandemic, and though it recovered some of these jobs in the subsequent months as people shifted to outdoor dining and delivery, half the pre-pandemic jobs were yet to return a year later. National employment in these industries also plummeted at the start of the pandemic, but recovered more quickly, reaching 70- 80 percent of pre-pandemic levels in early summer 2020, and a continuing trajectory upward through the January resurgence, and another recovery in March. Data for last summer and early fall is not yet available but will undoubtedly reflect a slowdown due to Delta.

The spread of outdoor dining changed the streetscape of the city, with sidewalks and parking spaces occupied by tables (and, later in the year, enclosed structures). Even though the number of patrons that restaurants could serve outdoors was a fraction of the regular indoor occupancy, outdoor dining gave many parts of the city the appearance of vitality that belied its ailing economic health.

By the time of the first Penn IUR Recovering Cities meeting in September 2020, the public health situation had improved, but its impacts were quite present. Unemployment remained very high, particularly in the Bronx (25 percent as of July 2020), Queens (21 percent), and Brooklyn (20 percent). Office buildings were largely empty, with only around 7 percent of workers returning.

Real estate sales volumes were still only half of pre-pandemic levels. The residential vacancy rate was above 5 percent, compared to the virtually full occupancy that the city was accustomed to prior to the pandemic. The 5 percent mark is also significant because, hypothetically, a vacancy rate of over 5 percent is meant to trigger the relaxation of rent stabilization regulations (though this largely went unnoticed).

The subway was a quarter as full and buses were half as full in September 2020 as they had been before the pandemic. While air travel had resumed, it was only one-fifth of pre-pandemic levels. The pedestrian traffic in normally busy Manhattan locations like Times Square and Grand Central Station was one-fifth of the pre-pandemic volume. Office districts like Midtown and the Financial District were virtually deserted. Clearly, in addition to the metrics around COVID-19, the importance of tourism and physical office occupancy was paramount in considering the impact of the pandemic on the city. As will be seen below, these data changed over the course of the year

The Recovering Cities Initiative

At the group’s first meeting, participants predicted that it might take years for the city to achieve full economic recovery. They speculated on which changes in patterns of work would become permanent. Participants expressed great concern over the fate of the restaurant industry, cultural institutions, Broadway, tourism, and the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s finances. It was also clear that the presidential election was adding to uncertainties about federal support to the city. In his comments, Byron Wien of Blackstone anticipated Donald Trump’s attempts to dispute the election results.

In the following months, real estate sales recovered, reflecting a significant decrease in rental rates and sale prices. Pent-up demand led to sales volumes in some months even exceeding those of the equivalent pre-pandemic months. However, by most other metrics, the city was far from fully recovered. And while the emergence of the Delta variant in summer 2021 delivered a blow to the city’s recovery trajectory, it did not put the city back to the worst days of the pandemic.

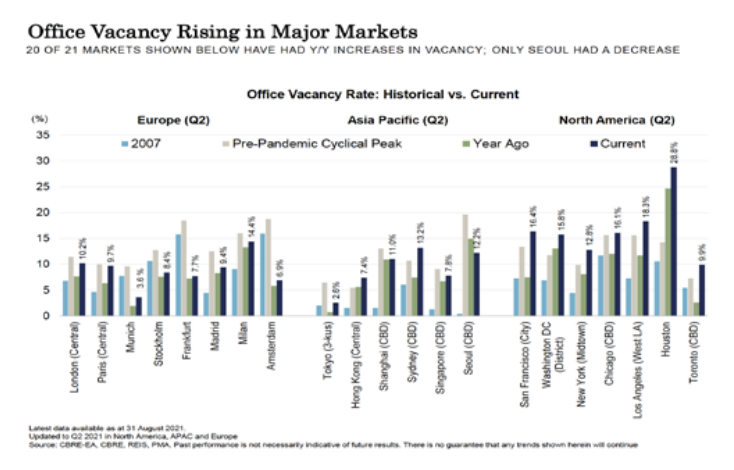

Figure 4: Assessment of office vacancy rates in 21 major markets reveals U.S. cities in worse shape than those in Europe and the Asia Pacific (Source: Lasalle Investment Management September 2021 Macro Deck)

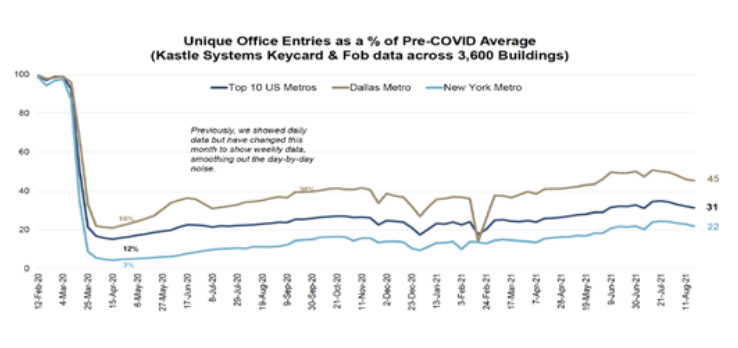

Figure 5: Unique office entries as a percentage of pre-COVID-19 average in the New York metro, ten top metros, and the Dallas metro, August 2021. (Source: LaSalle Investment Management September 2021 Macro Deck)

The unemployment rate remained in double digits, with the New York Metro reporting the worst performance in the nation’s top ten metros, ranking tenth in July 2021.1 Also, at that time the number of subway passengers were still at less than half of pre-pandemic numbers. A month later, pedestrian volumes in Times Square and Grand Central Station were down 42 percent and 65 percent respectively from pre-pandemic levels.

A study of six major U.S. commercial districts from late August 2021 showed that office vacancy in midtown New York City (13 percent) was lower than similar sites in Chicago (16 percent), Houston (29 percent), LA (18 percent), San Francisco (16 percent) and Washington D.C. (16 percent).2 In comparison to other global cities, midtown vacancy rates were slightly, but not significantly, higher—London (10 percent), Paris (9.7), Shanghai (11 percent).3

Beyond vacancy data, an August 2021 by report by Lasalle Investment Management on office use as measured by keyboard swipes and fobs compared to a year earlier emphasized the absence of workers. While the top ten metros recorded a 12 percent rate, the New York metro’s was a miserable 2 percent based on a 3,000+ building sample. Others report a higher rate—10 percent. Regardless, the numbers are low.

The New York Partnership’s return to office (RTO) survey of Manhattan employers in August struck a brighter note. While it indicated 44 percent delayed September openings due to Delta, they did expect that 76 percent of employees would return by January 2022.4

In September, murders, shootings, and car thefts were higher than in the equivalent months in 2019 but lower than at the same time in 2020 as the spike in crime in New York dated from 2020 and reflected a broader increase in crime in U.S. cities during the pandemic. For example, homicide rates in large cities were up more than 29 percent on average in 2020, and increased by another 10 percent in early 2021.5 Nonetheless, while homicide rates were well below historic rates, the increase in both years was significant due to its potential impact on the return of tourists and office workers. Popular accounts of these data has had a dampening effect on many groups’ desire to return to work.

In the group’s meetings during these months, presentations from regular and guest participants highlighted important aspects of the recovery and its historical and political context. In the January 2021 meeting, the eminent historian Kenneth Jackson presented an overview of the historical crises New York City had faced and survived. He was optimistic about the city’s ability to recover from the pandemic because of its core strengths of geography, diversity, density, and tolerance. In particular, he acknowledged that he had relatively late in life come to fully appreciate the essential role that the cultural and entertainment sectors play in attracting talented people of all industries to New York. In the March 2021 meeting, New York Times writer David Goodman discussed the upcoming mayoral election. He explained that due to several factors, including online campaigning, the early primary date, the introduction of ranked choice voting, the large number of candidates, the candidates’ lack of name recognition, and others, this mayoral election season was unlike any the city had seen before.

In the May 2021 meeting, Kathy Wylde, President and CEO of the Partnership for New York City, discussed the fiscal challenges that the city was facing due to the flight of employers and wealthy individuals in response to high taxes. She noted that the city still had two years before it could spend the funds it had appropriated, at which point it would drop off a fiscal cliff unless it corrected course. She discussed the efforts that her organization was making to develop a consensus around a practical, non-ideological fiscal strategy that the next mayor could take.

1 https://www.bls.gov/cew/latest-numbers.htm

2 https://www.lasalle.com/documents/Macro_Indicators_September_2021.pdf&n…;

3 https://www.lasalle.com/documents/Macro_Indicators_September_2021.pdf&n…;

4 New York Partnership, Return to Office Results Released – September 2021. https://pfnyc.org/news/return-to-office-results-released-august-2021/; https://pfnyc.org/news/return-to-office-results-released-august-2021/&n…;

5 Neil MacFarquhar, “Murders Spiked in Cities Across the Nation” New York Times, September 27, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/27/us/fbimurders-2020-cities.html

The group looked at seasonal trends in the next months. They returned to the hospitality and entertainment sectors in July, when Fred Dixon, CEO, NYC & Company and Tyler Morse, CEO, MCR Hotels, provided an overview of current conditions and plans for a national come-to-New York campaign launched to attract domestic visitors. And in September, the “Back to School” session featured Jennifer Raab, president, Hunter College who related the effect of the pandemic on the CUNY system in general and on Hunter and its associated K-12 schools in particular. Two important observations she made were that online learning was proving not to be a successful way to teach and that in the public elementary and high schools, a year of learning was essentially lost, with potentially significant ramifications in the future. Maxine Griffin, former executive vice president for government and community affairs, Columbia University, added a perspective from a private university, noting its importance of this seventh largest employer in the local economy.

Concerns Going Forward

Midway through the year, Penn IUR decided to test the group’s assessment of the timing of the city’s recover through a simple survey asking each one to predict when things would return to “normal.” The group were cautiously optimistic, supporting the prospect of recovery by the end of 2021, though not much sooner. Their responses, along with discussions during meetings, guest presentations, and the dashboard indicators together pointed to certain important areas of concern going forward. The following elements appear to be key for the city to return to normal.

Office Occupancy

According to estimates generated by the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) based on data from a sample of the city’s large commercial building owners, the physical occupancy rate of offices that was around 6 percent in July 2020, and had risen to nearly 20 percent in September, outpacing the metro data outlined earlier in this report. Manhattan office vacancy rates were 15.4 percent in Q3 in contrast to 10 percent in Q3 2020. However, the extended period of working from home appears to have prompted many employers and employees to reconceive the role of the office, possibly in ways that will have permanent effects. In the November 2020 meeting, Rit Aggarwala (then at Sidewalk Labs, now at Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute’s Urban Tech Hub) discussed possible changes in the role of Manhattan office space. He suggested that it would be reoriented towards meetings and events rather than independent work, which would continue being done remotely at least for a few days a week. He observed that if many companies had a Tuesday through Thursday schedule, there might not be such a reduction in the amount of space companies may need. He also speculated that during those days in the office, much of the business entertaining that might be spread out over the course of five days would be concentrated in those three days in the office, which might mitigate the expected negative impact on local retail of fewer workers in the office five days a week. It would also change the balance of the regional economy as well as regional commuting patterns.

In her presentation in the May 2021 meeting, Kathy Wylde noted that most employers were not forcing workers to return to the office, partly because of the increased likelihood of workers changing jobs during the pandemic, which has made employers fear losing workers. By August 2021, Wylde’s New York Partnership RTO survey reported that 70 percent of employers expect hybrid working arrangements to be permanent. If this plays out, many sectors from hospitality to commercial real estate will feel the impact.

Tourism, Arts, and Entertainment

In the summer of 2020, the arts and entertainment industry lost half its jobs, and more than a year later most of these jobs had yet to return. During the March 2021 meeting, Emily Rafferty, President Emerita of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, explained the challenges faced by performers who lack savings and have not been able to rehearse. However, she also noted that they have shown resourcefulness in adapting to their situation, often with the help of support from philanthropic organizations and the federal government. In March, venues had started to partially reopen, despite limited budgets and significant restrictions on attendance. Ms. Rafferty predicted that in coming months, the warmer weather would see innovative use of outdoor space for various activities, a phenomenon that did occur, exemplified by Jazz at Lincoln Center’s city-wide performances or the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s River to River festival. The Metropolitan Opera, Carnegie Hall, and Broadway were yet to reopen. Broadway, in particular, was identified as a major factor in attracting tourists and until there was a robust Broadway schedule, tourism would not return to previous levels. She described the performing arts sector as “holding its collective breath” to see how the next months would unfold. She explained that while there were no reliable statistics, mostly 500-1,000 seat theaters appeared to have closed, either temporarily or permanently. These included minority-owned, outer borough, and Off-Broadway venues. She noted that international tourism was unlikely to return quickly, with a full return possibly taking until 2025. The fact that the March 2021 volume of air passengers using the region’s airports was less than half of pre-pandemic levels suggested that tourism and business travel were still far from achieving a full recovery.

The group revisited the hospitality and entertainment sectors in July 2021 when NYC & Company’s Fred Dixon estimated that the tourismdriven sector would not return to 2019 levels until 2023 with leisure travel leading the revival and that business travel would not match 2019 until 2025. To assist in enlivening the industries, he outlined his group’s intensive campaign to woo residents and domestic tourists back to the city. Tyler Morse, CEO, MCR Hotels, provided an overview of the hotel industry, noting that the occupancy rate of the city’s 140,000 hotel rooms—100,000 in Manhattan— was at 40 percent including the homeless. As with Emily Rafferty and Fred Dixon, he speculated that a September recovery could be plausible, especially with the expected opening of Broadway. However, he offered a cautionary note that would apply to many other sectors, labor shortages were severe and hampering the return to business.

The emergence of Delta put a slight dent in the projections for a September recovery. While many Broadway shows did open in that month, and several employers like JP Morgan brought their workers back, others postponed their return to October and, in some cases to January 2022, while others were not committing to a specific date but were watching and waiting as city, state, and public officials pressed the population to get vaccinated.

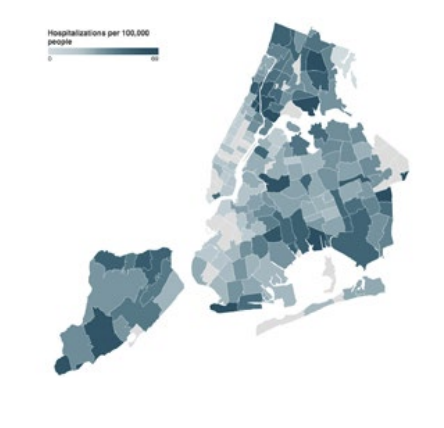

Figure 6: Hospitalizations by zip codes late August-early September (Source: NYC Health)

Transmission and Vaccinations

While city-wide cases, hospitalizations, and deaths were decreasing from their July/August 2021 peaks, the rates varied dramatically by zip code. As Figure 6 indicates, great variation in transmission exists across the city as represented by hospitalizations. For example, Central Harlem, Ocean Hill/Brownsville, Maspeth, and Tottenville (Staten Island) hospitalization experienced a 60+/100,000 rate in August in contrast to rates in the Upper East Side, Upper West Side, and Brooklyn Heights of 12/100,000. City data associated major differences in hospitalization with vaccination rates—lower levels of vaccination equaled dramatically higher hospitalizations.

Preventing another wave of COVID-19 infections in New York and allowing the city to reopen fully clearly relies on vaccinating as many people as possible. The city has made steady progress on this by mid-September, having administered more than 11 million doses resulting in nearly three-quarters of the city’s adult population being fully vaccinated. While the vaccines were proving highly effective against Delta, it remains uncertain whether enough people will agree to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity, or whether holdouts would prevent this from happening. The governmental mandates requiring proof of vaccination for entry into indoor venues (restaurants, sports venues, and fitness centers) and for specific groups of employees (education, health, government employees) aimed to address vaccine hesitancy. Nonetheless, vaccination rates vary by ethnicity and geography: as of mid- September 2021, 45 percent of Black residents had received at least one dose, compared to 60 percent of Hispanic/ Latino residents, 52 percent of white residents, and 81 percent of Asians, Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.6

Education: Universities, Colleges,and Associated Schools

After a series of school closings and reopenings over the 2020-2021 school year, the city is reopening all its schools in the fall of 2021 and ending remote learning. One of the great concerns with the return to in-person instruction was how to make up for the loss of the previous year’s learning, especially among children from disadvantaged families for whom remote learning was a disaster either due to a lack of access to computers or other reasons. The fear is that this loss will be felt for years to come.

The CUNY system is also offering in-person classes, targeting a 60 percent return rate for the Fall semester; Hunter has achieved 68 percent. Barriers to full in-class instruction at all levels include ongoing parental fears for unvaccinated children under 12 and teacher/staff resistance exacerbated by Delta. In September, Hunter College president, Jennifer Raab, speaking for the CUNY system outlined the precipitous decline in enrollment in community colleges as well as those located in disadvantaged communities. In relating the Hunter story, she reported on the college’s precautions and associated increase in enrollment. This phenomenon has led her to conclude that the pandemic is disproving a long-held belief that online courses or MOOCs would soon be the dominant form of instruction in higher education. College students crave in-classroom instruction she insisted.

Transit

The sudden drop in transit ridership to practically none at the start of the pandemic, followed by its sluggish recovery over the subsequent year, raised questions about the long-term financial health of the city’s transit system. During the September 2020 meeting, Regional Plan Association president Tom Wright explained that transit was safer in terms of virus exposure than people realized, and that it most likely was not responsible for driving spikes in the number of cases. Still, he predicted that it would be two to three years before transit ridership returned to pre-pandemic levels. A year later, this prediction was playing out. As of September 2021, subway and bus ridership are 48 percent and 44 percent of their 2019 levels respectively.

The MTA’s finances were in particularly bad shape in fall 2020, recovered in 2021, but structural deficits remain. In September 2020, the MTA was burning through its operating capital, spending $200 million a week, anticipating a deep deficit. However, within a few months, the situation improved as the MTA used the Federal Reserves’ Municipal Liquidity Facility to borrow $2.9 billion, and later, infusions of federal aid—$10.5 billion for the CARES and ARA acts, anticipated toll revenue increases through 2024, and the use of deficit borrowing ($1.3 billion) enabled the MTA to balance its budget through 2025.7 Further, the infrastructure bill has provisions for more funding. However, after 2025, the future is uncertain especially if people returned to working in the city only part time as revenues could be lower while operating expenses could remain high.

In September 2020, under reduced ridership, transit crime was lower in absolute terms than in the equivalent period in 2019; but it began to rise in March 2021 and continued to do so through September 2021. Nonetheless, along with Delta, the high level of public concern about transit crime further threatened the return of office workers who rely on transit, and the city’s economic recovery in general.

Public Safety

Fears about diminished public safety threatens the recovery of many sectors. There were more murders, shootings, and car thefts in September 2021 than in the equivalent months in 2019. Violent crimes, e.g. shootings, were concentrated in lower income neighborhoods in the Bronx, Upper Manhattan, and parts of Brooklyn. High profile crimes in tourist areas, such as a tragic shooting in Times Square, though limited in number compared to the crime in low-income neighborhoods, captured news headlines. An alarming spike in hate crimes, including incidents against Asian-Americans received significant press attention. For example, 114 hate crimes were reported through September 2021 compared to 24 during the equivalent period in 2020, a 375 percent increase.8 A bit of bright light emerged in September as crime statistics across all categories were lower than the equivalent time in 2020. The perception of out-of-control crime most likely led to Eric Adams, a former police officer, winning the Democratic nomination for mayor, an issue he will have to deal with if and when he assumes the office in January 2022.

Fiscal Challenges

Members of the group, as well as Kathy Wylde during her remarks as an invited speaker, expressed concern about the city’s budget. While there had been concerns early in the pandemic about a massive drop in tax revenues, by September 2021 they had increased 14 percent over 2019 due to a variety of reasons including the city receiving some $22 billion from the federal stimulus acts and the increase in online consumer spending. This aligned with higher-than-expected tax revenues nationally as well. However, a change in leadership in Congress following the mid-term elections or the easing of assistance signaled by Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell in late September will likely lead to a reduction in federal aid to the city. Meanwhile, the city’s high tax rates combined with the impending Biden tax reform may cause the highest taxpayers in the city to relocate. The effect of these changes could lead to a major fiscal crisis in the city. Members felt that the current state and city administrations are not taking this situation seriously.

The Citizens Budget Commission (CBC), a nonpartisan nonprofit group, confirmed this fear in its May 2021 report arguing that the city was spending its federal aid too quickly. According to the CBC analysis, the city frontloaded 2/3 of the funds in its 2022 budget, leaving only 12 percent for 2024 and 7 percent for 2025. In fact, the CBC concluded that the federal aid is being used “to fund recurring programs and spreading it thin among many initiatives and restorations that may not be of significant value.”9 This will lead to a fiscal “cliff” in 2026, with a budgetary shortfall of up to $4 billion which would particularly affect the Department of Education.

6 Vaccinations by Demographic Groups, September 2021. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-vaccines.page#nyc

7 https://new.mta.info/press-release/federal-funding-provides-mta-financi…;

8 https://abc7ny.com/NYC-crime-nypd-stats-New-York-City/11006492

9 https://cbcny.org/research/federal-aid-now-fiscal-cliffs-later

Conclusion: Resilience and Uncertainty

For much of the past year, the potential for a variant was not a principal focus. In fact, at the July session, neither Fred Dixon nor Tyler Morse expressed much concern about the risks of a variant. Obviously, as the summer progressed, the speed with which the Delta variant became a dominant concern was the primary COVID story. Whether Delta is a temporary setback or a phenomenon that will upend all positive momentum that had begun to emerge in the City is something we will only learn with the passage of time.

Over the last century, New York City has endured fiscal crises, terrorist attacks, extreme weather events, and countless other challenges, and yet managed to remain one of the most vibrant and attractive cities for residents, business, and tourists anywhere in the world. The pandemic, along with fiscal and political challenges, have created deep uncertainty about the future of the city. The experts convened by Penn IUR remain cautiously optimistic that the city will rebound, but also aware that plenty of work needs to be done to ensure that this happens.

For more information, including the Dashboards, see https://penniur.upenn.edu/recovering-citiesproject.