The G20 (or Group of Twenty), a collection of the world’s 19 largest economies and the European Union, began as a convening of finance ministers and central bankers in 1999. Within a decade, these ministers placed national leaders at the helm. The leaders hold annual summits and issue communiques that receive significant media attention and, more important, set global frameworks to guide and coordinate national and international policies aimed at ensuring global financial stability. The establishment of the G20 has added heft to the institutions created by the post-World War II Bretton Woods agreement, namely the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. It provides an arena for developing consensus-based cooperation on global matters. Over time, the G20 has broadened its portfolio to address a variety of issues relevant to the worldwide economy and to include other voices in advising them. This is where cities come in, a subject that this article will detail as it discusses the U20 (or Urban Twenty), one of seven G20 engagement groups.

G20 Influence and Decision-Making

Although the G20 summits, which typically occur in the fall, are newsworthy, G20’s overall influence is less well-known. Unlike the IMF, World Bank, and the United Nations, the G20 has no permanent secretariat or active communications mechanisms; these are left to the presidency that rotates annually among its members. However, the G20 members represent two thirds of the global population and produce 80 percent of the global GDP.

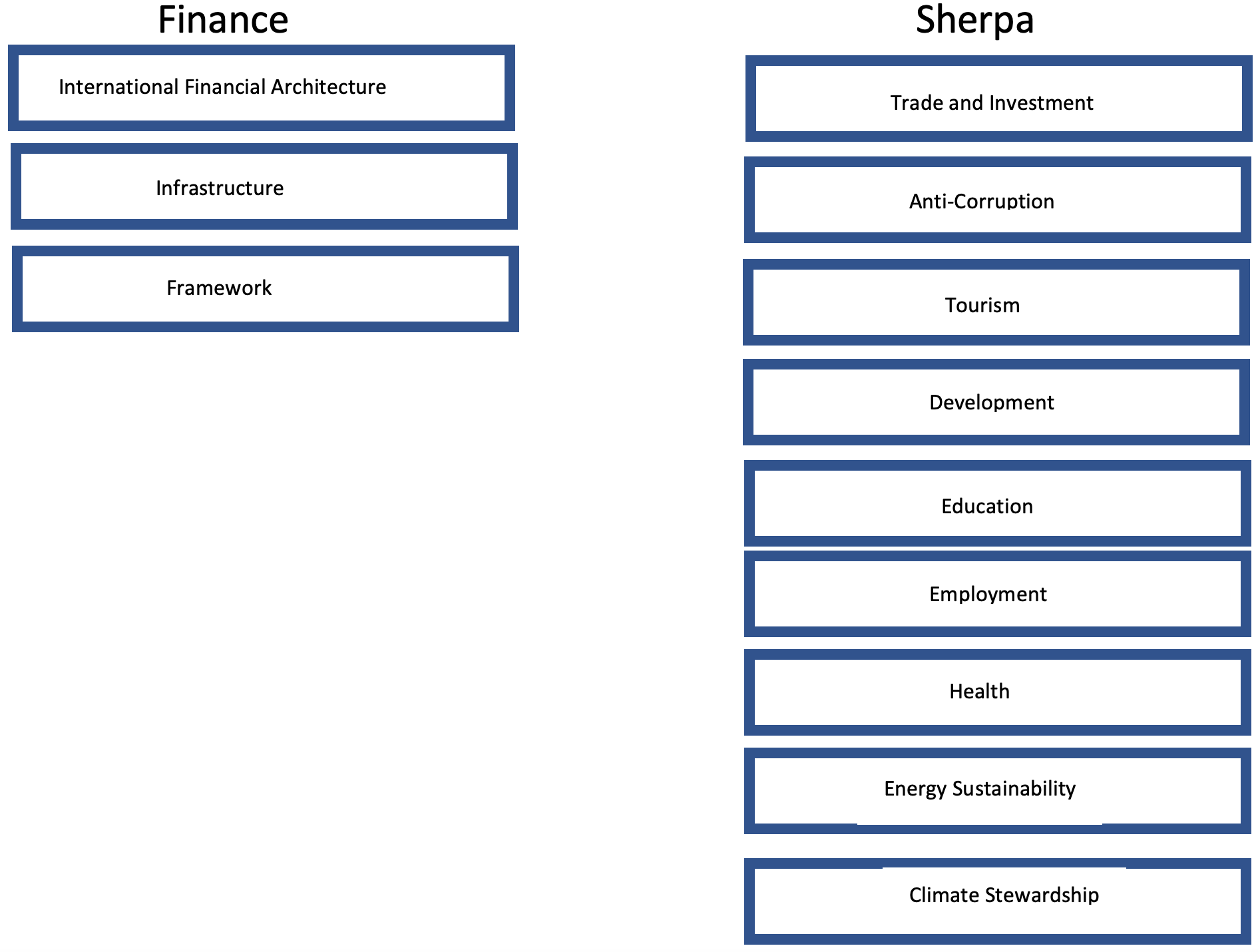

Massive preparations for each G20 summit occur throughout the year. The presidency organizes the work streams under two tracks, Finance and Sherpa: each track sponsors task forces, workshops, and special meetings whose findings are fed into the leaders’ summit communique (see Figure 1 for the activities in 2020 when Saudi Arabia was host).

Figure 1: G20 Organization: Finance and Sherpa Tracks

Between December 2019 and November 2020, Saudi Arabia, which held the presidency, hosted more than 100 meetings among ministers (e.g. Agriculture, Education, Energy, Environment, Health, Labor), working groups (e.g. Infrastructure, Employment, International Financial Infrastructure, Tourism, Climate Stewardship, Anti-Corruption), task forces (e.g. Digital Economy, Transport), and workshops (Border Management Issues, Energy Sustainability, Synergy between Adaptation and Mitigation). While these meetings capture less public attention than the leaders’ summit, their outcomes shape the leaders’ communique that references their work in the body of the declaration. For example, in March and April the G20 convened extraordinary meetings on the pandemic for the leaders and finance ministers and central bankers that resulted in the G20’s Action Plan to Support the Global Economy through the Crisis. The plan provided debt relief for developing countries, supported the World Bank’s setting aside $16 billion for COVID-19 assistance, and vowed to address the vulnerabilities revealed by the crisis. The G20 Leaders’ Summit Communique acknowledged and endorsed these commitments.

The Rise of the Engagement Groups

Over time, many international institutions including the UN, the G20, and others have recognized the need to include non-national government players in their deliberations—but not their decision-making. So these institutions have developed special arrangements to hear a wider array of voices to inform their policies and programs. Since 2008, the G20 has recognized engagement groups, now numbering eight. The G20 started with two in 2008 B20 (business) and L20 (labor); added two in 2010, C20 (civil society) and Y20 (Youth); then added others in 2012, T20 (think tanks); in 2015, W20 (women); in 2017, S20 (science); and in 2018, U20 (urban). This article focuses on the U20.

Each engagement group develops its own agenda and task forces, publishes policy papers, holds a summit, and issues a communique submitted to the host country for consideration by the leaders’ summit. This year, the engagement groups submitted hundreds of policy proposals to the G20 president. A university-based entity, the G20 Research Group, synthesized them into what it considered the 20 top recommendations. Among them are three suggested by the U20. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Top 20 Proposals Generated by Engagement Groups (U20 highlighted and sources, with groups and communique paragraph, indicated in parentheses, from November 2020 brief published by the G20 Research Group)

Making the Way into the G20 Deliberations: The U20 Example

The engagement groups channel their views to the G20 through consensus-building processes that ultimately result in submission of their own specialized communiques to the G20 president. Along the way, they interact with each other and make presentations to the various groups in the Finance and Sherpa Tracks.

In 2017 during the One Planet Summit in Paris, the Urban 20 (U20) was launched by conveners, C40 Cities and United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), under the leadership of the Mayor of Buenos Aires, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta and the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo. The U20 is a city diplomacy platform that gathers cities from G20 countries and observer cities from non-G20 countries to analyze, debate and develop joint positions on such critical urban issues, as climate change, inequality and sustainable economic growth. In 2018, Buenos Aires hosted the first U20 Mayors Summit; and in 2019 Tokyo hosted the second edition. While the U20 is the youngest engagement group, it has evolved quite quickly. It serves as an example of the means by which non-national groups can contribute to the G20 deliberations. It aims to advance the urban agenda with the top economies of the world. In this case, it represents a powerful group—cities—that have increasingly become players in the international arena due to their demographic and economic influence. For the G20, for example, the combined populations of the cities participating in U20 make them the equivalent of the world’s fifth most populous nation and, collectively, they would be the world’s third largest economy after the United States and China. They contribute 8 percent of the global GDP.

As with the G20, the U20 chair rotates with the presidency. For 2020, Fahd Al Rasheed, President of the Royal Commission for the City of Riyadh—assisted by U20 Sherpa Abdul Mohsen Al Ghannam, a city planner with the Royal Commission—headed the U20, whose membership consists of mayors. This year, it involved 44 mayors from among the G20 members (with 14 nations represented), plus leaders of five observer cities. In addition, the U20 taps assistance from knowledge partners drawn from universities to civil society organizations. This year the 31 knowledge partners included three working in a leading capacity. The University of Pennsylvania was one of the three.

Over the course of the preparatory period starting in September 2019, the U20 was extremely active. It held a workshop, two Sherpa meetings, and a summit. At the first Sherpa meeting, held in February 2020, it founded three Task Forces (Circular, Carbon Neutral Economy; Inclusive Prosperous Communities; Nature-Based Urban Solutions), each headed by a city and a knowledge partner. See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Participants in the U20 Preparatory Process

(Source: U20 Riyadh)

The groups worked collaboratively for several months to develop 15 Task Force white papers covering such topics as the circular economy, energy efficiency, mobility, affordable housing, women and youth empowerment, ecosystem services, water, and food systems. The authors threaded three themes through the paper: the localization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), climate/resilience infrastructure finance, and innovation and technology. The crafting of the findings was a fast-track, labor-intensive project, involving more than a 100 participants using remote communications to accomplish the work. PricewaterhouseCooper’s Cities and Local Government practice team, led by PwC Global Leader Hazem Galal, assisted the process. The recommendations from the white papers made their way into the U20 Summit Communique. See Figure 4 for a list of the white papers.

Figure 4: The U20 Task Forces

(Source: U20 Riyadh)

Later, with cities in the frontline of the spreading pandemic, the U20 chair organized a Special Working Group on COVID-19 and Future Shocks, headed by Buenos Aires and Rome and assisted by nine other cities. The group collected timely data through an extensive survey that gathered information on more than 20 cities altogether representing 75 million people and collected 32 case studies that illustrated various city responses to the disease. It charted the need for special services, the effects on cities’ fiscal situations, reforms needed to make the international financial system more city-friendly and ideas for how to recover and build back better post-COVID.

Three centers from Penn played active roles in each of the three Task Forces and the Special Working Group. Kleinman Center for Energy Policy’s Cornelia Colijn, Mark Alan Hughes, and Oscar Serpell were the lead authors of Efficiency and Diversification: A Framework for Sustainably Transitioning to a Carbon-Neutral Economy, Penn IUR’s Eugenie Birch was lead author of The Post-Covid-19 Circular Economy, Transitioning to Sustainable Consumption and Production in Cities and Regions, Penn IUR’s Susan Wachter and Perry World House’s Michael Horowitz and Jocelyn Perry advised on several papers in each Task Force. Finally, Perry World House’s Visiting Fellows Ian Klaus and Mauricio Rodas, along with Eugenie Birch, wrote Financing Cities’ Recovery from Covid-19 and Preparing for Future Shocks.

While this work was going on, U20 representatives engaged in outreach to the G20 organization. For example, the U20 chair addressed the Extraordinary Virtual G20 Leaders’ Summit in March to discuss the effects of COVID-19 on cities. He participated in other key leadership meetings: he presented the U20 process at the third G20 Sherpa convening, addressed a Finance Track symposium, and attended the G20 Extraordinary Digital Economy Ministerial Meeting, offering insights on Smart Cities that found their way into their Smart Cities Guidelines. U20 representatives also attended the Tourism Working Group meeting as well as eight other working group meetings on relevant topics. Finally, U20 worked with C20, L20, T20, W20, and Y20 groups that contributed to U20 white papers.

The preparatory work concluded with a virtual Urban Summit, held September 30 to October 2. It attracted more than 300 attendees including 174 representatives from 44 cities, 64 representatives from 24 knowledge partners, representatives from five engagement groups, 12 national and regional governmental bodies, 45 national and international organizations, and one representative from the G20 Finance Track.

The participants attended side events and official meetings. The seven side events treated a range of topics—from delivering the UN’s SDGs in cities, to smart cities, to social inclusion. In the official meetings, the mayors heard the Task Force and Special Working Group on COVID-19 and Future Shocks findings. Each Task Force detailed the recommendations from each white paper under its direction, followed by mayor-led panel discussions.

Among the policy recommendations was one from the Special Working Group that captured universal attention at the Urban Summit. It called for a city-led Global Urban Resilience Fund (GURF), an agile entity to provide timely access to investment in infrastructure and municipal services to increase the urban resilience around the globe in times of crisis. Strong support for this idea emerged because cities cannot directly access most international financial institutions that are managed by national governments. As envisioned, GURF would enable independent local government transactions. The participating mayors endorsed the idea of the fund, the Saudi government supported it, and (with the transfer of the presidency to Italy, December 1, 2020) Rome and Milan, the U20 host cities, will continue to develop it.

The U20 Summit Communique, the output of the Urban Summit, calls for multiple actions organized under four themes followed by detailed recommendations. The themes are:

- Partner by investing in a green and just COVID-19 recovery

- Safeguard our planet through national-local collaboration

- Shape new frontiers for development by accelerating the transition to a circular, carbon-neutral economy

- Empower people to deliver a more equitable and inclusive future

Ultimately, 39 cities signed the communique, a record for U20. At the conclusion, the U20 chair presented the communique to the Saudi presidency.

So Did U20 Matter?

When the G20 leaders met in November 2020, they were, as was the U20, deeply concerned about the pandemic and its destabilizing effects on global, national and local economies. This theme runs through their ten-page, four-part communique. While the words “city” and “urban” are absent (as are “rural” and “country”), the G20 statements certainly encompass the issues highlighted by U20’s Task Forces and Special Working Group on COVID-19.

In addition to dealing with global financial and trade issues that are outside of U20 mandates, the G20 leaders offered strong commitments to building back better, focusing on areas of great impact in cities. In The G20 Leaders’ Communique, they called for strengthening health systems and safe transportation, investing in technology infrastructure while bridging the digital divide, and supporting smart city’ efforts. They paid special attention to an inclusive recovery, promoting decent jobs, and social protection for the vulnerable and for informal economies. They strongly promoted a sustainable future that treated energy efficiency and endorsed the circular, carbon-neutral economy including mobility and food systems. They embraced tackling climate change and biodiversity loss and called for the provision of affordable, reliable, and safe water, sanitation, and hygiene services, all critical to cities.

So all in all, was the U20 effort worth all the activity?

The answer is yes—for at least two reasons that the players will relate in their own cities and countries.

First, the U20 work forged a consensus among the member and observer cities on critical issues related to the economic, social, and environmental underpinnings of global financial stability. This agreement strengthened the chair’s presentations to the Extraordinary Virtual Leaders’ Summit, the Sherpa convening, and several ministerial working groups. It supported the U20’s collaboration with other engagement groups. Thus, its work allowed the U20 voice to be heard and pointed out cities’ important roles as strong partners with nations in supporting G20’s goals.

Second, the U20 produced a concrete outcome, GURF, the city-led financial facility, to assist cities in developing a more prosperous and resilient future, the details of which will be the charge of the next U20.

Finally, the U20 arena provided a space for city leaders to forge new relationships and partnerships. These connections are horizontal—with other engagement groups, each having its expertise and mutual interests—and vertical—with national leaders each having functional responsibilities, again touching on key urban concerns. They form a broad and diverse network for the exchange of knowledge and practice to help inform, strengthen, and offer innovation for public and private decision-making in meeting the global challenges.

Eugénie Birch is Penn IUR Co-Director and Nussdorf Professor of Urban Research, Department of City and Regional Planning, Stuart Weitzman School of Design.