Between 1990 and 2010, Mexico’s largest 100 urban areas added 23 million new residents, a more than 50% increase. Nearly all of this new growth has been in densely populated suburban neighborhoods, comprised of informal housing or — more recently — large, dense, publicly-subsidized, and peripherally-located commercial housing developments. This shift in urban spatial structure has likely contributed to the rapid increase in vehicle fleets and vehicle travel in Mexico. National and local government agencies have attempted to contain sprawl and its associated costs — such as pollution, long and expensive commutes, congestion, and traffic fatalities. For example, the National Housing Commission (Comisión Nacional de Vivienda, CONAVI) recently developed an Urban Growth Containment Program to promote more centralized construction of publicly subsidized housing. The Federal government’s recently approved 2016 New Human Settlements Law will allow for higher densities and mixed-use development throughout Mexican neighborhoods starting in 2018. Nonetheless, between 1990 and 2010, the vehicle fleet tripled in Mexico’s largest 100 largest urban areas.

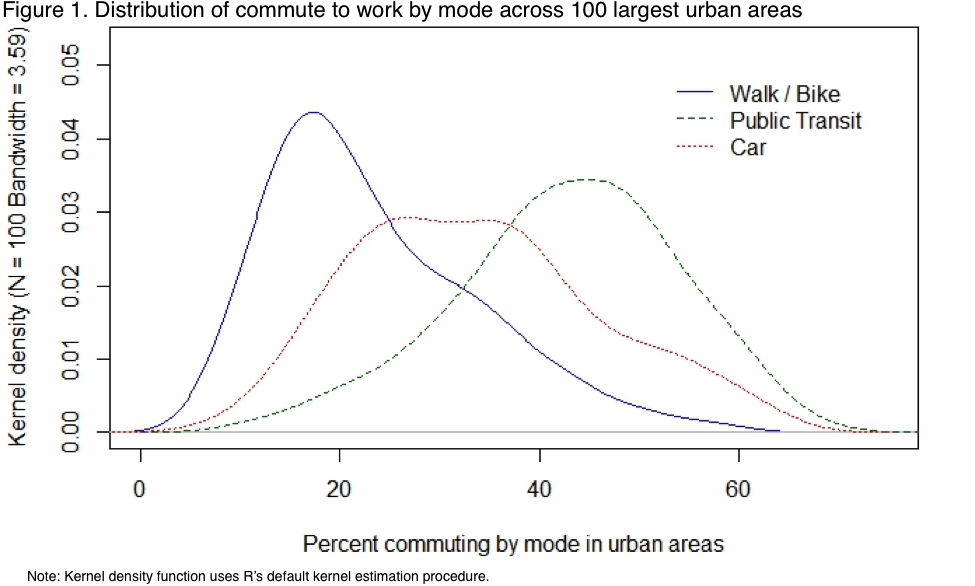

Despite the rapid growth in vehicle fleets, Mexico’s urban areas remain highly multimodal, with 49% of residents commuting to work by transit, 28% by car, and 23% by foot or bicycle. (See Figure 1.) Figure 1 plots the distributions of mode share across the 100 urban areas as three kernel-smoothed histograms. Public transit is the most common way for people to access work and accounts for between 12% and 67% of trips in each urban area. Public transit mode share includes buses, minibuses, microbuses, minivans, workplace shuttles, and all types of taxis (shared or unshared), in addition to trains, metro, and bus rapid transit (BRT). In some cities, such as Tijuana, shared taxis are particularly important to the public transportation system. In northern cities with a high share of employment in large factories, such as Juarez and Chihuahua, worker shuttles are particularly important and support around a quarter of all work commutes. Only 1% of commuters relied entirely on a mass rapid transit system like BRT or rail. Another 3%, mostly in Mexico City, relied on a combination of informal transit and a mass rapid transit system.

To inform academic understanding of this issue and contribute to policy debates in Mexico, my coauthors and I collected data and estimated models to examine whether and to what extent measures of urban form and transportation supply relate with how people commute to work in Mexico’s 100 largest urban areas. Although there is a large and growing body of literature on the relationship between urban form and travel behavior, little evidence comes from Latin America and virtually none from smaller cities. As in other low- and middle-income countries, however, nearly all of Mexico’s recent and projected population and economic growth is now occurring outside of its largest cities (United Nations Population Division 2014). How smaller cities grow will help determine national car ownership levels, total vehicle travel, pollution levels, and traffic safety records.

We found that Mexico’s urban commuters are much more likely to travel by transit in dense cities, with spatially clustered job centers, limited roadway, and good transit supply. Urban areas with similar features, but a more even balance between jobs and population and perhaps also a compact, circular shape, tend to favor commuting by foot or bike. Low-density cities with poor transit service and substantial amounts of roadway almost certainly and unsurprisingly favor driving. Overall, population density, roadway density, and local transit supply are more strongly and consistently related with mode choice than the other measures of urban form. In a car-friendly urban area — as estimated using the 25th percentile values of the metropolitan measures associated with lower probability of commuting by car — we expect 37% of work commutes to be by car, compared with 29% in a typical city, and 18% in an urban area more suited to transit, walking, and biking. Most of the modal substitution is from cars to transit and transit to cars. In the 75th percentile car-friendly urban area, 42% of commutes are by transit, compared to 57% in the 25th percentile car-friendly urban area. That a 75th percentile car-friendly city has twice the expected driving rates as a 25th percentile one suggests that changes in urban form and transportation supply have the potential to result in economically, socially, and environmentally important shifts in driving rates over time.

While we conclude that land use and transportation supply relate to commuter patterns as strongly as household attributes like income and size, we find that current trends and national policies are likely to drive increased automobility in the coming decades, as well as associated changes in congestion, emissions, and traffic collisions. Despite stated intentions to increase the use of public transport rather than motorized modes, existing land use and transportation policies are almost certainly contributing to the growth in car ownership and car travel. The most important land use policy of the past 20 years has publicly subsidized the creation of large low-to-moderate income housing developments on the urban periphery, far from existing job centers or transit supply. Simultaneously, public investments have strongly favored road infrastructure, with the occasional centrally-located high-capacity transit investment. Together, these two policy shifts have converged to support the substantial growth of vehicle use in Mexico’s cities. Stemming the tide of rising motorization will require a concerted shift in public policy.

Erick Guerra is a Penn IUR Faculty Fellow and Assistant Professor of City and Regional Planning at the Penn School of Design. Guerra’s research focuses on transportation and urban form.The research in this article first appeared in the October issue of Transport Policy. For the full research article see: Guerra, Erick, Camilo Caudillo, Paavo Monkkonen, and Jorge Montejano. 2018. “Urban Form, Transit Supply, and Travel Behavior in Latin America: Evidence from Mexico’s 100 Largest Urban Areas.” Transport Policy 69 (October): 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.06.001.