Advancing the Urban Climate Finance Agenda: The Green Cities Guarantee Fund

By Mauricio Rodas

The Need for New Urban Finance Mechanisms

Cities are at the forefront of addressing some of the world’s most pressing challenges, including poverty, inequality, inadequate access to basic services, and climate change. As urban populations continue to grow—now comprising over half of the global population and projected to reach 70% by 2050 (UN 2018)—the role of cities in tackling these issues becomes even more critical, adding complexity to local governance and significantly increasing the financial demands on cities.

However, cities face a global financial system rooted in the Bretton Woods framework, which was designed with a focus on nation-states and offers limited financial access to subnational governments. This system, established in the 1940s, was created in a far less urbanized world. Today, the reality is vastly different, and this outdated structure is ill-suited to address the global challenges that are now concentrated in cities.

A striking example of the dysfunction in the current system is that the majority of countries—56%—prohibit cities from borrowing. Only 44% of nations permit cities to access international finance, but even then, cities must meet stringent requirements (PressWilliams et al. 2024). In many countries, this involves obtaining a sovereign guarantee, which is frequently withheld due to political tensions between national and local governments. Additionally, many cities lack the technical expertise to develop viable, bankable projects. Other barriers, such as high interest rates, short loan terms, complex and lengthy approval processes, or outright credit denial, further hinder cities from accessing the finance needed to implement critical projects.

Furthermore, according to the World Bank (2017), “recent estimates show that less than 20% of the largest 500 cities in developing countries are deemed creditworthy in their local context, severely constricting their capacity to finance investments in public infrastructure.” This challenge is compounded by the fact that future urbanization is projected to occur primarily in medium and small-sized cities across the Global South, where resources and institutional capacities are even more constrained.

Cities account for over 70% of global CO2 emissions and, due to their demographic, economic, and environmental characteristics, are pivotal in the fight against climate change. Without cities playing an active and effective role in addressing the root causes of the climate crisis, countries will never meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and the goals of the Paris Agreement. Although many mayors worldwide have embraced bold and ambitious climate agendas, the slow pace of funding for essential mitigation and adaptation projects—or worse, the complete lack of access to finance—has severely impeded progress. According to the 2024 State of Cities Climate Finance report by CCFLA (Press-Williams et al. 2024) an estimated US$ 4.3 trillion per year will be needed to transform urban infrastructure into a climate-resilient one, a figure that is unattainable for cities under the current financial system. This report estimates that annual urban climate finance amounts to only US$ 831 billion, while other assessments suggest that cities have received less than 10% of the US$ 1.9 trillion currently available for annual climate finance (Lütkehermöller 2023).

Most funding for urban climate infrastructure projects in the Global South has come from Development Financial Institutions (DFIs), but this represents only a small fraction of the resources required given the scale of the climate crisis. Furthermore, the nation-led governance structure of traditional DFIs offers little incentive to depart from the status quo and direct the necessary resources to subnational governments.

It is evident that the current system is no longer effective. Without reforms in the international financial architecture to provide alternative financing mechanisms for cities, they will continue to struggle to address climate change. Numerous stakeholders have called for a financial system that better aligns with urban needs, offering a range of innovative proposals. For instance, the 2020 Urban 20 Chairmanship introduced the pioneering concept of the “Global Urban Resilience Fund.” Another notable idea is the creation of a “Green Cities Development Bank,” proposed in 2019 by C40 Cities and others in the report “Financing a Sustainable Urban Future: Scoping a Green Cities Development Bank” (Alexander et al. 2019). In addition to other meaningful initiatives being pursued in this space, the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Global Commission for Urban SDG Finance has been developing over the past year the concept of a cities-focused guarantee fund aimed at facilitating timely and affordable borrowing—a potential game-changer for unlocking finance for many cities and advancing the urban climate agenda.

The SDSN Global Commission for Urban SDG Finance

In Paris, on June 21, 2023, Mayor Anne Hidalgo of Paris, Mayor Eduardo Paes of Rio de Janeiro, and SDSN Founder and President Jeffrey Sachs officially launched the SDSN Global Commission for Urban SDG Finance, where they serve as co-chairs. Today, the Commission includes over 80 members, comprising mayors, governors, climate and finance experts, leaders of city networks, practitioners, and scholars. Its members hold key positions in municipal and regional governments, international organizations, development finance institutions, investment firms, consulting companies, civil society organizations, and academic institutions. The Commission’s Secretariat is hosted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Urban Research, providing essential support to its mission.

The Commission builds on the expertise and ongoing efforts of its members to advance innovative solutions and strategies aimed at enhancing urban SDG financing, with a particular emphasis on addressing climate change. Through collective collaboration, the members have formulated a series of actionable recommendations, including the proposal for the Green Cities Guarantee Fund (GCGF).

In the report titled The Green Cities Guarantee Fund: Unlocking Access to Urban Climate Finance from the SDSN Global Commission for Urban SDG Finance, the Commission’s Secretariat offers a comprehensive analysis of the Green Cities Guarantee Fund concept. This analysis is based on an extensive literature review, assessments of guarantee fund annual reports, and numerous interviews with current and former mayors, climate finance experts from both the public and private sectors, guarantee fund specialists, national government officials, and professionals experienced in launching and incubating new development finance entities and funds.

Key Challenges in Urban Climate Finance

Cities in low- and middle-income countries face significant obstacles to securing affordable debt for development and climaterelated projects. One primary issue is the global financial system’s country-focused structure, which channels most development finance through national governments rather than directly to cities. National governments control fund distribution, often without considering local priorities. While reforms to Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) are being discussed, city-specific financing needs have been mostly overlooked. Lenders and rating agencies also perceive cities as high-risk due to political instability, limited institutional capacity, and a lack of resources to carry out complex projects. As a result, cities that can access financing often face high interest rates and short loan terms, which can strain the budgets of local governments and increase the likelihood of default.

However, the European Investment Bank (EIB) found evidence indicating that the actual risk of lending to cities is relatively low, which runs contrary to the commonly held viewpoint of investors (EIB 2023). A 2022 analysis comparing default rates of private and subnational borrowers, using pooled data from major DFIs revealed that from 1994 to 2022, subnational borrowers had a lower average default rate (2.2%) compared to private borrowers (3.6%). This means that subnational governments were more likely to repay their loans than private companies over this period. Yet cities continue to be underestimated by investors, banks, and ratings agencies.

In countries where subnational borrowing is permitted, cities are often required to obtain sovereign guarantees for debt transactions. This provides lenders with assurance that the national government will step in and repay the debt in case of default. However, sovereign guarantees are an unreliable tool for cities to secure capital. Rigid fiscal frameworks make obtaining these guarantees a slow and bureaucratic process, causing significant delays for cities. Moreover, national governments may withhold or deny guarantees due to differing political priorities or a lack of understanding of municipal infrastructure needs.

Credit Guarantees Overview

Credit guarantees have the potential to address some of the core financing challenges that cities face today. But first, what is a credit guarantee? Put simply, a credit guarantee is a “promise to pay” (GCF 2022). More specifically, a credit guarantee is a commitment by a guarantor to repay a debt on behalf of a borrower in the event that the borrower cannot fulfill its debt obligations.

Guarantees provide an added layer of downside protection to lenders, encouraging investment in sectors and geographies that may traditionally be viewed as too risky. Guarantees generally enable borrowers to access debt on more affordable terms—as guaranteed transactions generally have lower interest rates and, in some cases, longer tenors.

Guarantee funds are neither borrowers nor lenders. So, what role do they play in infrastructure transactions? Guarantee funds play the role of facilitator in infrastructure projects. By providing credit enhancement, guarantee funds facilitate investment in projects that may not otherwise reach financial close.

Credit Guarantees within the Climate Finance Landscape

Climate finance involves a diverse array of investors from both the public and private sectors. Guarantees currently play a relatively insignificant role in the climate finance sector which is dominated by loans, equities, and grants. Public contributors include governments, national and multilateral development finance institutions, multilateral climate funds, state-owned enterprises, and state-owned financial institutions. On the private side, commercial banks, corporations, households, or individual investors play significant roles. Today, climate finance flows exceed US$ 1 trillion annually (Buchner et al. 2023).

It is well known that there is not nearly enough public capital available to achieve the objectives set out in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which has drawn attention to the topic of expanding private investment in climate solutions (UN 2023). Research by the Blended Finance Task Force (BFTF) highlighted that credit guarantees are both highly effective at mobilizing private capital for climate projects and underutilized by development finance institutions, such as the World Bank. Their findings showed that MDBs currently mobilize just 30 cents of private investment for every dollar of loans allocated to climate projects—a capital mobilization ratio of 0.3 (Neunuebel et al. 2021). By contrast, between 2012 and 2018, climate-focused guarantees provided by MDBs had a capital mobilization ratio of 1.5, which is 5 times higher than that of loans. By expanding the share of guarantees within their climate portfolios, MDBs may be able to dramatically expand the amount of private investment they crowd in for climate projects.

Recently, climate-oriented guarantee funds have emerged to address environmental challenges. GuarantCo, founded in 2005 in partnership with the UK Foreign Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO), has issued US$ 1.9 billion in guarantees for sustainable infrastructure in Africa and Asia. [2] The Green Guarantee Company (GGC), launched in 2024, is a US$ 1 billion fund, andthe first emerging markets climate-focused guarantor with backing from the Green Climate Fund and several governments.

Furthermore, there’s evidence that credit guarantees may be able to stimulate the growth of municipal debt markets. In the United States, credit guarantees/insurance were highly correlated to the growth of what is today a US$ 4.1 trillion market (GlobeNewswire 2023). In the developing world, no country has a municipal debt market near the size or sophistication of the United States. However, several countries across Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia, have growing subnational debt markets that have not reached their full potential (Smoke 2019). Introducing citiesfocused guarantee funds to these countries could directly support the growth of subnational debt markets, enabling more cities to access finance for critical infrastructure.

There are important city-focused guarantee initiatives now in the early stages of implementation. The UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) is launching its Guarantee Facility for Sustainable Cities, with a strategic focus on Africa and Southeast Asia, while the French Development Agency (AFD) has established Cityriz, a guarantor for local governments in Africa. Both facilities are in the process of deploying their first guarantees. The Green Cities Guarantee Fund aims to complement these and other significant efforts in addressing the financial challenges cities face across various regions of the world. The Green Cities Guarantee Fund and its Potential The proposed Green Cities Guarantee Fund (GCGF) seeks to address some of the key urban financing challenges. The GCGF would act as an intermediary between lenders and cities, incentivizing lenders to provide loans to cities that may lack a history of creditworthiness. For cities, these guarantees could improve their credit ratings, reduce borrowing costs, extend loan and bond terms, and broaden access to investors. This Fund would be flexible in its mandate and designed to support a range of green projects through various debt instruments available to cities, associated entities, and the private sector.

The potential of the GCGF is significant. It could boost local debt markets, increase municipal participation in global capital markets, foster public-private partnerships, and attract private investment in urban infrastructure. The GCGF could support diverse markets and investors, strengthening the urban climate finance sector in general.

Similarly, the GCGF can demonstrate the viability of local banks lending to cities on a commercial basis. In some emerging markets, domestic commercial lending to local governments is already common, as local banks recognize the potential in financing cities. However, in most countries, commercial banks either perceive cities as too risky or cities are restricted from accessing commercial capital altogether.

The GCGF could also help cities tap global bond markets, which are largely dominated by hard currency transactions. These transactions, while protective for lenders, pose risks for cities that generate revenue in local currencies, exposing them to exchange rate fluctuations. The GCGF could mitigate these risks by structuring guarantees in partnership with platforms that help hedge currency risk and assisting cities in accessing grants to cover hedging fees. The ability to borrow in local currency is crucial for mayors in many countries, particularly in developing nations. The GCGF would have the flexibility to support operations in either hard or local currency, tailored to the specific context of each project. GuarantCo’s successful implementation of local currency guarantees across Africa and Asia illustrates the viability of this model.

In addition, the GCGF could help cities navigate Green, Social, and Sustainable (GSS) bond issuances. With GSS bonds becoming a US$ 1 trillion market, dominated by the US, Europe, and China, there is significant opportunity for cities in emerging markets to participate. However, municipal issuance remains rare, comprising less than 1% of the market in 2023 (World Bank 2024). The GCGF could help cities overcome barriers to issuing GSS bonds by offering support in structuring deals, ensuring compliance, and managing reporting requirements.

Some cities have developed essential urban infrastructure through publicly owned utility companies or Special Purpose Vehicles—SPVs. This approach is particularly beneficial for cities that are legally unable to borrow or struggle to obtain the sovereign guarantees required to access financing. For instance, in 2017, the French Development Agency (AFD) provided a US$70 million loan to Quito’s Water and Sanitation Municipal Company for a key water supply and sustainable treatment project that serves over 500,000 residents.

The company’s strong financial standing allowed it to secure this financing without the need for a sovereign guarantee—the first time this has occurred in Ecuador—since the legal requirement for such a guarantee only applies to credit operations conducted directly by the city. The GCGF could play a key role in supporting similar initiatives by mitigating risks for investments in projects developed by utilities or SPVs, solidifying these models as effective solutions for expanding climate-resilient urban infrastructure.

The funding supports critical infrastructure projects, including the Chalpi Grande-Papallacta project, which aims to capture 2.2 cubic meters per second of water from the Chalpi Grande River and its tributaries. This will secure Quito’s water supply until 2040, benefiting over 500,000 residents. The loan also finances the expansion of the Paluguillo Water Treatment Plant and the construction of the Paluguillo-Parroquias Orientales Transmission Line to deliver treated water to parishes in eastern Quito. A notable aspect of the project is the installation of a 7.6 MW hydropower plant, designed to optimize water resource management and contribute to the project’s overall financing.

One way to provide subnational governments with access to capital is through public-private partnerships (PPPs), where subnational governments are shareholders in a company or project. Private sector ownership and involvement in municipal infrastructure projects can generate greater investor confidence. In countries with underdeveloped subnational debt markets, municipal PPPs could be a key channel through which cities can access greater capital for mitigation and adaptation infrastructure. The GCGF could provide credit guarantees for green, municipal PPPs, and also provide technical assistance to cities structuring PPPs.

Besides supporting municipal debt and public-private partnerships, the GCGF can also provide guarantees for private sector-led urban infrastructure projects, such as water systems, energy, waste collection, and public transit, among others. In many countries, private companies can secure the right to develop projects through concessions awarded by municipalities to design, build, and operate public infrastructure. The GCGF could support these companies in raising funds through domestic or international capital markets. A notable example of such a private sector guarantee is GuarantCo’s US$ 25 million guarantee for the Lagos Free Zone in Nigeria. [3] This enabled a US$ 65.5 million bond issuance, facilitating the development of the country’s largest port-based economic zone, which has attracted US$ 2.5 billion in private investment to the Lagos metropolitan area.

Next Steps: Operationalizing the Green Cities Guarantee Fund

The first step in moving the GCGF from a concept to an operating fund is defining its structure and governance framework, capitalization model, and hosting institution. Crafting a robust and sustainable business model is also key. As a hybrid entity combining insurance and development finance functions, the GCGF’s goal is to be self-sustaining, drawing revenue from guarantee premiums and returns on its assets. The next phase will focus on conducting comprehensive technical studies to refine these critical elements.

In this context, the Commission Secretariat conducted preliminary analyses of regions, countries, and sectors to guide a market study for the Green Cities Guarantee Fund (GCGF). The analysis considered urbanization rates, infrastructure gaps, subnational funding, and enabling environments. It also examined the availability of public development assets and the geographic distribution of existing guarantee funds, noting that Latin America holds just 4% of the world’s guarantee funds. Based on this research, the Secretariat has identified Latin America and the Caribbean as a high-potential region for the Fund’s initial pilot phase, with plans to expand globally in the future.

The Secretariat also briefly reviewed the specific types of urban infrastructure projects of interest to the GCGF. They are public transport, energy, water and sanitation, local public infrastructure, waste treatment and disposal, nature-based solutions, and climate disaster risk management. Moving forward, the market study needs to develop performance and risk profiles for these sectors. It should also identify the public or private entities that are responsible for them in each selected country, as national governments can take very different approaches to infrastructure financing and development (Almeida et al. 2022).

In addition to backing up infrastructure projects, the GCGF could also offer flexibility in supporting institutional financing aimed at strengthening municipal governance, enhancing planning and procurement processes, and building operational capacities for the implementation of climate initiatives. A prime example of the type of operations that could be guaranteed by the GCGF is the AFD’s US$ 120 million credit to the city of Barranquilla in 2020. This financing supported the implementation of the City’s Development Plan, focusing on sustainability, climate adaptation, biodiversity conservation, and social inclusion. Notably, this marked AFD’s first local currency operation in Latin America, underscoring the potential impact of such initiatives on urban development in the region.

One major question that investors, bankers, lawyers, and other stakeholders who may be unfamiliar with the urban climate finance space ask is—do cities want this? To further build a case for the GCGF, the Commission Secretariat will seek to establish a pipeline of cities that are actively raising green financing and receptive to working with the GCGF. This stage will involve engaging with city leaders who want to develop climate mitigation and adaptation infrastructure in their cities. This process is expected to unveil the strong enthusiasm from city leaders throughout the developing world who are ready and willing to take bold climate action and seek innovative finance mechanisms to do so.

Additionally, partnering with a wide range of organizations will be instrumental to the successful launch and operations of the GCGF. The GCGF is a unique vehicle in that it combines elements of municipality, climate, and development finance. Cities, national governments, civil society organizations, development finance institutions, climate funds, investment banks, ratings agencies, institutional investors, urban finance consultants, law firms, and more will collectively form a network of partners with the GCGF.

Momentum for the Creation of the Green Cities Guarantee Fund

Global efforts to increase climate finance for cities have gained significant momentum. In 2023, the UAE COP Presidency and Bloomberg Philanthropies hosted at COP 28 the Local Climate Action Summit, the first event of its kind, focusing on local-level climate finance and energy transition. The creation of the Coalition for High Ambition Multilevel Partnership (CHAMP) initiative, endorsed by over 70 nations, aims to integrate subnational governments into the development of the next Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), potentially expanding cities’ access to climate finance.

Some DFIs are also playing a significant role. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s (EBRD) Green Cities program has mobilized more than US$ 5 billion in investments across 50 cities, while the City Climate Finance Gap Fund, managed by the World Bank and European Investment Bank, has provided technical assistance to 183 cities in 67 countries since its launch in 2020. [4] CAF, the Development Bank for Latin America and the Caribbean, has made significant strides in expanding its support for subnational governments. In recent years, CAF pledged a substantial portion of its capital towards lending to subnational entities, such as municipal governments and local projects, through innovative financial mechanisms, some of which do not require a sovereign guarantee (CAF 2022). Relevant international players, such as the OECD and UN-Habitat, offer critical data and policy support, helping cities navigate climate finance. City networks like C40, ICLEI, GCoM, and the Resilience Cities Network are at the forefront of pushing for more financing for urban climate projects.

The proposed GCGF, along with other city guarantee mechanisms currently being established, represents a timely and strategic initiative. This effort has the potential to significantly enhance financial flows toward the development of climate-resilient urban infrastructure.

The GCGF does not aim to be a universal solution to urban financing challenges. Its impact will not extend to every city, nor will it support every project. A guarantee, by nature, cannot transform a poorly designed project into a successful one; only projects with solid foundations are eligible. However, the GCGF holds the potential to substantially enhance the urban climate finance landscape, emerging as one of several critical tools needed to address the growing demand for sustainable urban infrastructure solutions.

The GCGF is designed to address the green financing needs of cities across diverse geographies and regulatory frameworks. In countries where cities are legally permitted to borrow without the need for a sovereign guarantee, the GCGF can help local governments access debt more affordably. In countries that require sovereign guarantees for subnational borrowing, or where cities are legally unable to borrow directly, the GCGF can facilitate urban infrastructure development by channeling capital to municipal utility companies, Special Purpose Vehicles, and the private sector.

In nations where sovereign guarantees are optional, the GCGF may serve as an alternative mechanism. In cases where cities and municipal public entities are completely prohibited from accessing capital markets, the GCGF shifts focus to supporting the private sector in securing finance for critical mitigation and adaptation infrastructure projects. This adaptability would enable the GCGF to benefit a large number of cities by customizing its approach based on local regulatory environments. Its focus in urban finance allows the GCGF to deliver innovative subnational financing solutions tailored to different needs and challenges in countries.

The GCGF is envisioned as an entity specialized in addressing the distinct dynamics of cities, including the political cycles and administrative timelines of municipalities, which often differ significantly from those of national governments. Urban projects also come with their own set of complexities, making tailored financial solutions essential. By specializing in urban challenges, the GCGF can serve as a pivotal mechanism to meet the growing financial needs of cities and respond effectively to the increasing pressures faced by urban areas. This specialization positions the GCGF as a relevant player in advancing urban development in a meaningful and targeted manner.

The time for action is now. Cities can no longer afford to fall short of their climate ambitions due to the constraints of an outdated financial system. To meet the urgency of the climate crisis, we must seize the current momentum in urban climate finance and develop innovative financial tools. These tools will empower cities to become pivotal leaders in the global fight against climate change, enabling them to implement bold and impactful strategies that are crucial for the planet’s future.

Alexander, James, Darius Nassiry, Sam Barnard, et al. 2019. Financing the Sustainable Urban Future. ODI, Working Paper 552. https://odi.org/en/publications/financing-the-sustainable-urbanfuture-scoping-a-green-cities-development-bank/.

Almeida, María Dolores, Huascar Eguino, Juan Luis Gomez Reino, and Axel Radics. 2022. “Decentralized Governance and Climate Change in Latin America and the Caribbean.” International Center for Public Policy Working Paper Series, AYSPS, GSU Paper 2207. International Center for Public Policy, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:ays:ispwps:paper2207.

Birch, Eugénie, Luke Campo, and Mauricio Rodas. 2024. The Green Cities Guarantee Fund: Unlocking Access to Urban Climate Finance. SDSN Global Commission for Urban SDG Finance. https://urbansdgfinance.org/.

Buchner, Barbara, Baysa Naran, Rajashree Padmanabhi, et al. 2023. Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2023. Climate Policy Initiative, November 2. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2023/.

Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean (CAF). 2022. “CAF approved USD 14+ billion in 2022 to promote Latin America and Caribbean development.” December 29. https://www.caf.com/en/currently/news/2022/12/caf-approved-usd14plus-billion-in-2022-to-promote-latin-america-and-caribbeandevelopment/.

European Investment Bank (EIB). 2023. Default Statistics: Private and Sub-Sovereign Lending 1994–2022, Vol. 1. European Investment Bank. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2867/143223.

GlobeNewswire. 2023. “Global Trade Credit Insurance Market Report 2023: Surge in the Global Import and Export of Goods and Services Drives Growth.” GlobeNewswire, May 12. https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2023/05/12/2667900/28124/

en/Global-Trade-Credit-Insurance-Market-Report-2023-Surgein-the-Global-Import-and-Export-of-Goods-and-Services-DrivesGrowth.html.

Green Climate Fund (GCF). 2022. “Funding Proposal 197: Green Guarantee Company.” MUFG Bank, Ltd. Decision B.34/10, November 14. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/funding-proposal-fp197.pdf.

Lütkehermöller, Katharina. 2023. The Little Book of City Climate Finance. New Climate Institute. https://newclimate.org/resources/publications/the-little-book-of-city-c….

Neunuebel, Carolyn, Lauren Sidner, and Joe Thwaites. 2021. “The Good, the Bad, and the Urgent: MDB Climate Finance in 2020.” World Resources Institute, July 28. https://www.wri.org/insights/mdb-climate-finance-joint-report-2020.

Press-Williams, Jessie, Priscilla Negreiros, Pedro de Aragão Fernandes, et al. 2024. The State of Cities Climate Finance 2024: The Landscape of Urban Climate Finance, 2nd edition. Cities Climate Finance Leadership Alliance and Climate Policy Initiative.

https://citiesclimatefinance.org/publications/2024-state-of-citiesclimate-finance/.

Smoke, Paul. 2019. Improving Subnational Government Development Finance in Emerging and Developing Economies: Toward a Strategic Approach. ADBI Working Paper 921, February. Asian Development Bank Institute. https://www.adb.org/publications/improvingsubnational-government-develo….

United Nations (UN). 2018. “68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN.” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), 16 May. https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-ofworld-urbanization-prospects.html.

United Nations (UN). 2023. “Deputy Secretary-General Highlights Importance of Cooperation, Innovation in Addressing Global Challenges, at Indonesia Development Forum.” UN Press, October 3. https://press.un.org/en/2023/dsgsm1839.doc.htm.

World Bank. 2017. “City Creditworthiness Initiative: A Partnership to Deliver Municipal Finance.” Brief. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/brief/city-creditworthiness-initiative.

World Bank. 2024. Green, Social, Sustainability, and Sustainability-Linked (GSSS) Bonds. Quarterly Newsletter: Issue N. 6. Market Update, January. https://thedocs.worlbank.org/en/doc/dc1d70af2c45cb377ed3ee12b27399d4-03….

- This article is based on The Green Cities Guarantee Fund: Unlocking Access to Urban Climate Finance (Birch, Campo and Rodasa 2024).

- See more at: https://guarantco.com

- See more at: https://guarantco.com/our-portfolio/lagos-free-zone0company/.

- To know more about the ERBD Green Cities program, see it here: https://ebrdgreencities.com/green-cities-about/. For the EU Guarantee program, see the InvestEU Green Cities Framework: https://investeu.europa.eu/investeu-operations-0/investeu-green-cities-framework_en. And, finally, for the Green Climate Fund financing, see more at https://www.citygapfund.org/.

How the Cidade Maravilhosa Became More Marvelous, Lessons for the G20

By Eugénie L. Birch

As the G20 heads of state gather in Rio de Janeiro, these high-level visitors and their entourages will likely marvel at the city’s natural beauty, travel on its varied transport systems, enjoy its cultural assets–including the luminous Museum of Tomorrow–, and maybe even sneak a peek at samba school dancers preparing for Carnaval. They will probably remember Rio as the host of the 2016 Summer Olympics. And they will see a great city that lives up to its name, “Cidade Maravilhosa.” But will they ask, “How did Rio become so great?” Will they realize that its greatness results from the nation’s enabling conscious and intentional leadership having access to funding to meet the challenges and seizing the opportunities that make cities great—a phenomenon that also makes their parent nations great?

Will they make the connection from last year’s G20 declaration, One Earth, One Family, One Future which called for “enhanced mobilization of finances and efficient use of existing resources to make the cities of tomorrow inclusive, resilient and sustainable” and, in a word, great? (India 2023, 18). They can refer to the OECD report, Financing Cities of Tomorrow (2023), for guidance, but they might be better served by studying the city before them: Rio, it has much to tell them.

Great cities become great by design. Great cities are the work of heroic leaders who drive transformative projects and find ways to pay for them. Great cities are dynamic. Great cities are reinvented. The world knows how, when, and why some cities have become great over time because they have biographers. David Pinkney identified key qualities in Napoleon III and the Rebuilding of Paris (1958) as did Jan Morris in Venice (1960); Carl Schorske in Finde-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture (1980); Robert Hughes in Barcelona (1992); Geert Mak in Amsterdam (1995); Peter Ackroyd in London (2000); Simon Sebag Montefiore in Jerusalem (2011); and, most recently, Luke Stegemann in Madrid (2024).

In fact, some cities command multiple biographers. Take New York, for example. Its reinvention story started with American historian Robert Albion’s The Rise of the New York Port 1815–1860 (1939) and has gone forward to economist Edward Glaeser’s Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier (2012). He observed: “being headed for the trash heap of history in the 1970s,” the Big Apple’s entrepreneurial mayors not only enhanced the advantages of the city’s density, transportation efficiencies, and education but also made living in the city “fun.”

Rio de Janeiro joins the list of multiple biographers. To name a few: Norma Evenson’s Two Brazilian Capitals (1973) focused on design; Beatriz Jaguaribe’s Rio de Janeiro: Urban Life Through the Eyes of the City (2014) offered a sociologist’s view; Daryle Williams, Amy Chazkel and Paulo Knauss’s Rio de Janeiro Reader: History, Culture, Politics (2016) captured the city’s 450-year history; while Luis Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro’s Urban Transformations in Rio de Janeiro (2017) and Janice Perlman’ssequence, The Myth of Marginality: Urban Poverty and Politics in Rio de Janeiro (1980) and Favela: Decades of Living on the Edge (2010), shared the story at different geographic scales—from the metro to the neighborhood.

However, missing from Rio’s list is an updated tale of the city’s reinvention. Such a story takes Rio from the 1960s to the present, emphasizing how it serves as an example for other places in the rapidly urbanizing world. It shows how Rio has had its share of shocks: the loss of status as the country’s political capital in 1960

and subsequent economic and environmental difficulties (e.g. bankruptcy in 1988, drug-oriented crime, unrest and hyperinflation in the 1990s, landslides, and floods in 2010, 2011, and others). Yet, in the past decades, it has become a new, 21st-century

Rio, significantly reinvented, not perfect, but great.

This chapter begins to tell the story. It starts by outlining how the city absorbed massive population growth. It then provides a cameo of some transformative projects that enhanced its assets and addressed perceived liabilities. In a parallel effort, it explores Rio’s becoming an in-demand global center. The next topic illustrates the innovative governmental and municipal financing capacities used to support Rio’s greatness. Finally, it ends with three lessons for those who want to make their cities great.

Absorbing Three Million Residents in Two Generations

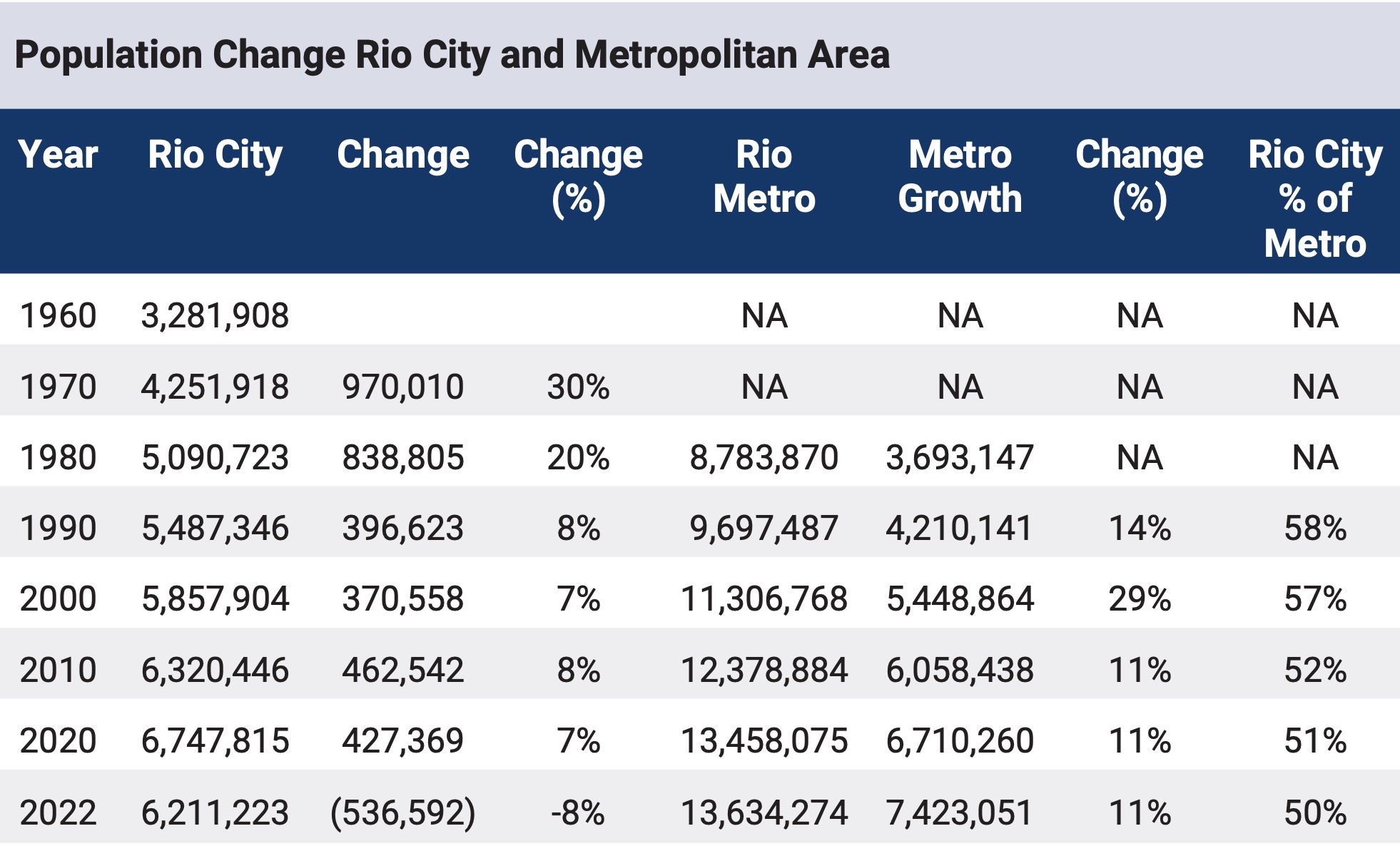

Few cities can successfully absorb massive population growth as has Rio. Between 1960 and 2020, some 3.4 million people moved into the city, with the population peaking at 6.7 million in 2022 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Population Change Rio City and Metropolitan Area. Source: IBGE.

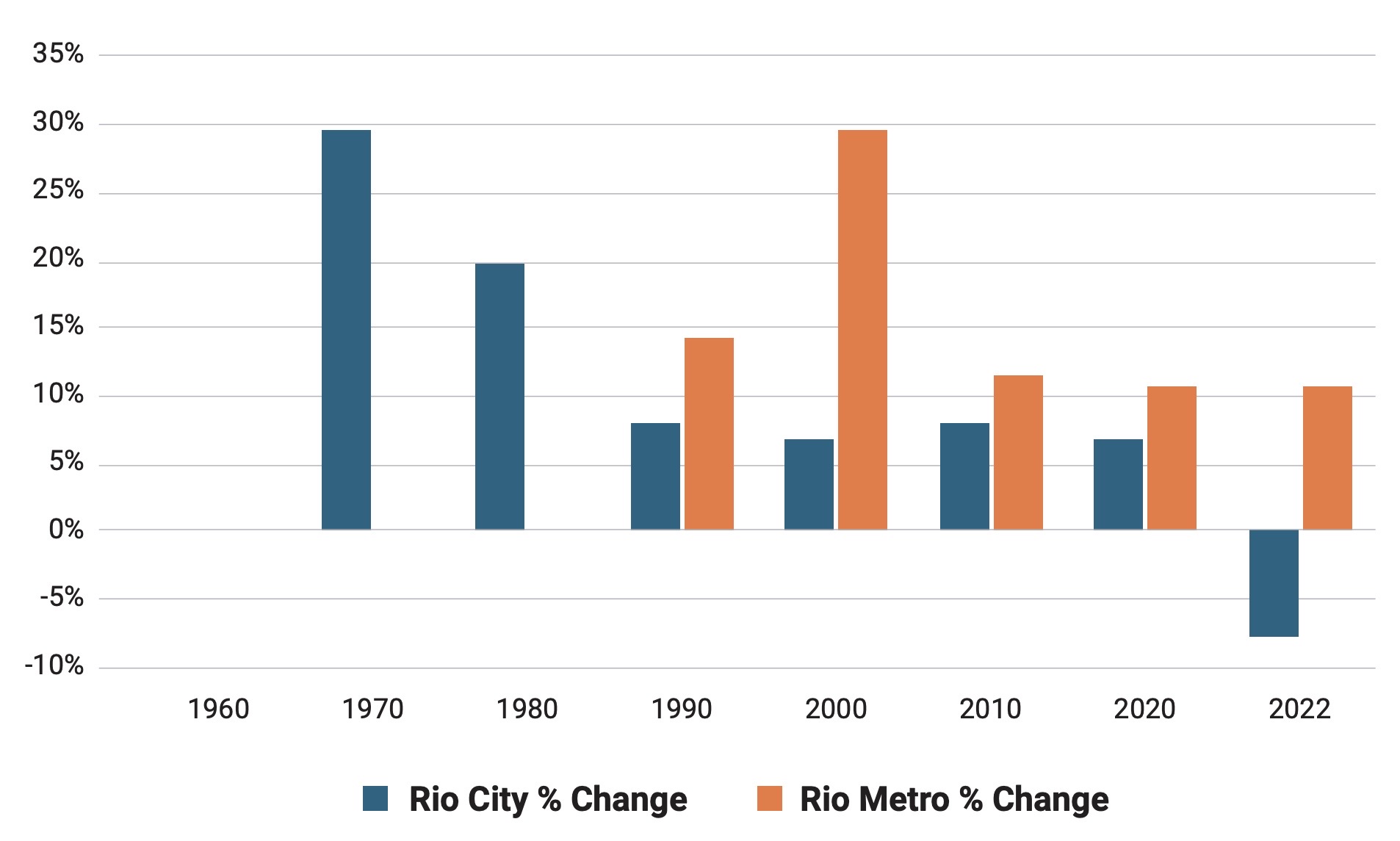

Over time, Rio has maintained a central position in its rapidly growing metro—more than 13 million in 2022. Of note is the half million population loss between 2020 and 2022, likely attributed to the suburban-like growth of the metropolitan area along with economic advances in surrounding cities in the state (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparative Growth Rates Rio City and Rio Metro 1980–2022 Source: IBGE.

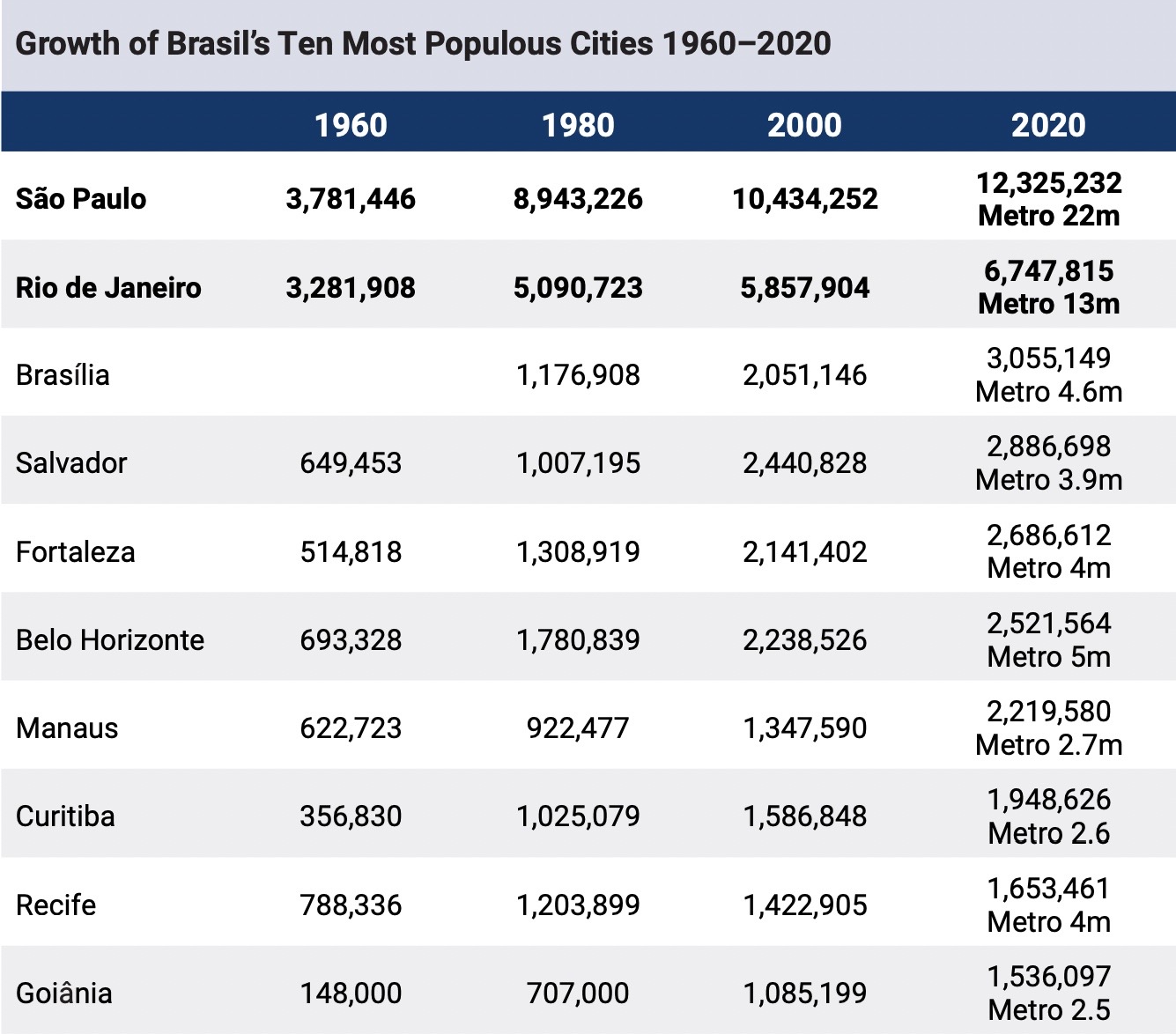

Rio’s growth occurred as Brasil was rapidly urbanizing: the country went from 46 percent to 66 percent urban between 1960 and 1980 and continued this trajectory, moving to 80 percent urban in 2000, and by 2020 some 87 percent of its population lived in cities. In 1960, São Paulo and Rio had populations of 3+ million—in subsequent years, both continued to grow along with other Brazilian cities. Some 65 percent of Rio’s growth came from internal migration, not a natural increase (see Table 2).

Table 2. Growth of Brasil’s Ten Most Populous Cities 1960–2020. Source: IBGE.

Brasil’s national development policies focusing on industrialization stimulated Rio’s (and other cities’) rural-to-urban migration. However, Rio was unprepared for the newcomers who then settled in informal settlements–or, as they are called in Rio, favelas–with numbers so high that many failed to find employment in the formal economy (Pino 1997). While some favelas in Rio predate the 1960s growth spurt (e.g., Providencia [1898] and Rocinha [1933]), most did not. As they came, they occupied the interstitial areas of the hilly city. By 1970, Rio would have an estimated 500 favelas; in 1980, more than 600; and today, about 1,000 (CatComm n.d.).

Rio’s favela population grew more rapidly than the overall one. For example, between 1980 and 1990, the number of favela residents increased 41 percent, and the city increased 8 percent. From 1990–2000, favelas grew 24 percent while the overall rate was 7 percent (O’Hare and Barke 2002).

Non-favela growth occurred along and immediately behind the city’s extensive waterfront. Over time, densification accompanied the population increases in every neighborhood, likely heightened by city investments in infrastructure (e.g., the metro starting in the 1970s) and open space amenities (e.g., Flamengo Park and Copacabana). Intense real estate development yielded high-rise apartments to accommodate the city’s middle- and upper-income residents, while self-help construction would transform fragile wooden shacks into more substantial brick and cinder block lodging in the favelas.

Rio’s surge in population growth took place against a background of Brasil’s dramatic political and economic turmoil as the country pursued various development policies. Between 1950 and 1964, Brasil had eight presidents, with only two (Juscelino Kubitschek [1956–61] and João Goulart [1961–64]) serving more than two years. A military coup in 1964 led to years of martial rule, ending in 1985. Runaway inflation, rising from 30.5% in 1960 to 79.9% in 1963 and 92.1% in 1964, contributed to the instability, a situation that would prevail to the early 1970s and re-occur from 1985–1994. As the country swung from democracy to authoritarianism and back to democracy, Rio also experienced major changes beyond population growth.

A major shock for Rio occurred in 1960 when President Kubitschek relocated the capital to Brasília. Rio then became its own state, Guanabara. This 564 square mile area existed for 15 years, overseen by three governors: Carlos Lacerda (1960–1965), Francisco Negrão de Lima (1965–1971), and Antônio de Pádua Chagas Freitas (1971–1975) who collectively pursued development policies focused on modernization. They attempted to provide basic infrastructure (the metro, sewer, and water) but could barely keep up with the population growth. They sought to eradicate favelas by moving the population to state-built housing settlements on the periphery of the city–but this strategy was politically unpopular and ultimately unsuccessful (Benmergui 2022).

After losing the capital status, Rio went into decline while its sister city, São Paulo, overtook it demographically. In 1950, the two cities had nearly equal numbers of residents (2.3 million in Rio and 2.1 million in São Paulo). In 1960, São Paulo grew a bit faster, surpassing Rio by only half a million people. However, between 1960 and 1970, São Paulo’s 55 percent growth rate yielded 5.9 million people while Rio, struggling to reinvent itself, experienced a lower growth rate (30 percent) that resulted in a 4.3 million population.

From the mid-1970s through the 1980s, Rio was the beneficiary of important administrative restructuring. In 1975, the military government–with the agreement of the two states’ governors– dissolved Guanabara and the neighboring Rio de Janeiro State. It reconstituted a new Rio de Janeiro State (area of 17,000 square miles), designating Rio de Janeiro as its capital with a mayor appointed by the state governor. In the following years, the 21-year military government gradually transitioned to democratic rule and, in 1982, provided for the popular election of mayors. It relinquished power in 1985. By 1988, the country had a new constitution, establishing it as a federal republic. Notably, the constitution’s strong decentralization provisions delineated state and municipal powers.

For cities, it specified the mayoral election process and term, city council size, and such competencies as the ability to levy taxes, regulate urban land and its development, and provide key services including mass transportation, elementary education, and health services. It mandated that large cities (more than 20,000 population) develop and regularly revise master plans (plano diretor) that had the force of law regarding land use. Rio complied with this directive. Of note, its 1993 master plan explicitly expressed a growth strategy focused on sports and culture (Silvestre 2012).

Transforming Rio through Major Projects: A Cameo

From 1960 to the present, Rio has been under a constant state of reinvention, overseen by leaders who intentionally focused on enhancing the city’s assets and addressing its liabilities. Most importantly, Rio’s leaders engaged in the conscious positioning of the city as a global center and found inventive ways to do it. While they viewed sports as critically important to this effort, they also encouraged other means—based on culture, multilateralism, and commerce (business and industry in association with academia)—to bring attention to the city.

Enhancing Assets

With its natural beauty, location, and climate, natural features and monuments have defined Rio’s role as Latin America’s most popular tourist attraction. For decades the city’s leadership has worked to protect and enhance its major assets: the beaches (e.g. Copacabana, Ipanema, and later Barra da Tijuca); open spaces (e.g. landfill-constructed Flamengo Park [1965]; and Sugar Loaf Mountain, reached by cable car [renewed in 2009]); and well-conserved monuments (e.g. Corcovado’s nearly 100-year-old Christ the Redeemer, located within the city’s 15 square miles of Tijuca National Park with its renowned 54 acres Botanical Garden [1808]).

Copacabana, for instance, offers an example of how Rio’s city and state leaders have consciously magnified its tourist attractions (Hoogendoorn et al. 2021). A few low-scale buildings and village streets bordered the beach at the turn of the 20th century, no seaside boulevard existed, and access from the center was limited. In the late 19th century, the city opened the Túnel Velho (1892) and Túnel Novo (1906) that linked to the historic center, leading real estate investors to develop the newly attractive sites as streetcar, later buses and, still later, metro operators extended lines from the center. As part of a larger beautification effort of Francisco Pereira Passos (mayor from 1902–1906), a pioneer in promoting Rio as a global center, the city added the first version of the Avenida Atlântica (1906) in front of the famous Copacabana Palace (opened 1923).

Copacabana Beach, in the late 1950s and 1960s, was 55 meters wide and was now bordered by high-rise apartments (height restricted through a 1937 zoning ordinance). A congested Avenida Atlântica ran along the side, and with some 3.5 million cubic feet of sand added between 1970 and 1972, the beach spanned 90 meters, and the Avenida Atlântica became a parkway bordered by the memorable Copacabana Promenade (1970). Designed by landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, the promenade featured an artistic version of the Portuguese traditional calçada, a paving design first used in Rossio Square in central Lisbon and in the earlier versions of the Avenida Atlântica in Rio. As part of this project, the city built another tunnel above Túnel Velho, increasing access to Copacabana, and thus stimulating real estate development—the area’s population peaked at 200,000 (Godfrey 2012).

Other than maintenance and regulation of public events, the city did little to the beach between the 1970s and the late 1980s. In 1990, however, the city promulgated a program, called Rio-Orla, to monetize, beautify and order the waterfront. Rio had a reason to undertake this effort because it had declared bankruptcy in 1988 (Simons 1988). The fortuitous approval of the nation’s 1988 Constitution offered a rescue as it gave cities new powers including jurisdiction over public space. Rio’s mayor seized the opportunity through the Orla Rio program, ordering the removal of unlicensed vendors and replacing them with regulated concessions. Within two years, Rio replaced 525 ragtag beachfront vendors, requiring the concessionaires to provide permanent kiosks supplied with water, electricity, telephone, and sewer located within a restricted area that left room for a bike path without “invading” the beach (Souza 2016).

A few years later, the Olympics planners chose Copacabana as the site for a temporary beach volleyball stadium. With its spectacular view of the sea, observers remarked, “As sporting communions go it takes some beating—sun, sea, sand, and beach volleyball on Brasil’s Copacabana in an open-air, 12,000-seater arena just meters from the waves crashing onto Rio de Janeiro’s golden shore,” said one as another declared: “Beach volleyball typically boasts one of the most scenic venues at each Olympics, especially Sydney and London—and Rio might contend for the best ever” (McGowan 2016; Ackerman 2016).

Copacabana was also featured in Rio’s efforts to deal with sanitation and storm sewers. Along with the 1970s beach refurbishment, the city constructed a large (5.5 m tall, 5 m wide) interceptor tunnel under the widened Avenida Atlântica to capture runoff from the surrounding hilly areas as part of a 9 km long sewer system to discharge at an ocean outfall in neighboring Ipanema beach. Yet, with ongoing population growth, managing sewers was challenging in the subsequent years. After the merger of Guanabara and Rio de Janeiro state, water and sewer service became the responsibility of a newly created Rio de Janeiro State Water and Sewage Company (CEDAE), an entity that struggled for decades to meet the demand for clean drinking water and sewer treatment. In fact, during the 2016 Olympics, Copacabana, the site for the triathlon and open water swimming, was subject to numerous news reports about its pollution and unsafe competition. Overall, Rio was unable to meet an Olympic pledge to provide water and sanitation services to 80 percent of the city’s population by 2016. By 2021, strapped for cash and unable to perform its functions, CEDAE auctioned sewer concessions to private sector entities based in Singapore and Canada, and some of the proceeds flowed to Rio’s municipal budget (Biller 2021; World Bank 2022).

To reinforce the necessity of enhancing other assets, Rio’s leaders worked with the state and federal governments to secure a highly sought-after world heritage site designation from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The nation’s Institute of the National Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN) initiated the nomination in 2009, within two years, the mayor submitted the key supporting documents, including the Master Plan for the Sustainable Urban Development of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro (City of Rio de Janeiro 2011).

The plan outlined management plans for the area containing the natural features (7,300 hectares) and a large buffer zone (8,600 hectares)—some 13 percent of the city’s land area. The buffer zone included several densely settled neighborhoods having almost half a million residents (IPHAN 2014). By 2016, the multi-year process was successful. This recognition would support the city’s tourist attractions and solidify the public stewardship of natural areas in the face of development pressures from the real estate sector.

In recent decades, mayors Cesar Maia (1993–1997; 2001–2009), Luiz Paulo Conde (1997–2001), and Eduardo Paes (2009–2013; 2013–2017; 2021–2024) focused on another set of assets, the city’s cultural amenities. They followed along the lines of earlier government leaders who had built the Municipal Theater (1909), National Library (1910), National Museum of Fine Arts (1938), and Museum of Modern Art (1955). In 2003, Maia commissioned the construction of the Cidade das Artes, a performing arts center in the fast-growing Barra da Tijuca neighborhood. Despite having a troubled history related to funding, it subsequently opened in 2013 as the largest modern concert hall in Latin America. With the samba placed on UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage in 2005 and flourishing in Rio’s Carnaval, both Maia and Paes would invest in supportive facilities: Maia funded the Cidade do Samba (2006) home to several schools, and Paes funded the expansion of the Sambódromo (2012), a nearly half-mile parade ground accommodating 90,000 spectators.

After a failed attempt to attract a branch of New York City’s Guggenheim Museum to Rio in 2005, Maia and later Paes remained committed to the use of culture in their quest to reinvent the city. The result was the addition of two architecturally dazzling museums to the city’s inventory. The first, the Rio Museum of Art (2013), featured the adaptive reuse of three buildings (a former port inspector’s headquarters [Dom João VI Palace from 1910], a former central bus station, and a police hospital from the 1940s). The second, the Museum of Tomorrow (2015), illustrated sustainable design through its use of solar energy and other devices. A recent evaluation of the museums concluded that they were successful in attracting local and tourist audiences and, in fact, the Museum of Tomorrow had become an “icon … being a symbol of Rio de Janeiro and object of countless shared images of the city… [and] is aligned with the process of city branding, which implies selling the image of the city as ‘a good destination’ for investment and tourism, generating symbolic and economic gains” (Corrêa et al. 2022).

The two new museums anchored the city’s 1,200+ acre Porto Maravilha urban redevelopment of the city’s port and its surrounds, an area long contemplated for revitalization (World Bank 2020). Developable land being limited, Rio’s once thriving port was rendered obsolete by technological advances in shipping accelerated high vacancy rates. Inadequate infrastructure and isolation from the waterfront by a two-mile elevated highway, the Perimetral (1950–78), were barriers to any spontaneous private sector investment. Rio’s winning the Olympic bid in 2009 gave impetus to the project, with the city placing the communications center there. [1]

Some 28,000 people lived in the port area that the city believed could accommodate 300,000 if redeveloped according to its $ 2.8 billion regeneration plan. PORAM, the plan, envisioned a special mixed-use community that combined existing and new residences, traditional and new-age businesses, and local and global arts and culture. Of note, in addition to building the new museums and making land available for modern office buildings, the city actively protected local character. For example, upon hearing of the eviction of more than 50 artists from a derelict factory they had transformed into studios, Mayor Paes expropriated the building, putting it under city ownership and retaining its function (Clarke 2012). A key piece of PORAM was the massive reconfiguration of the area’s infrastructure, including dismantling the Perimetral and replacing it with a 17-mile light rail, a two-mile promenade for bikes and pedestrians, and five miles of tunnels as well as water and sanitation infrastructure, electricity, gas, telecommunications, and public lighting (World Bank 2020).

Addressing Perceived Liabilities

While Rio engaged with such new projects as the Porto Maravilha, it also began to address what might be called a perceived liability, its massive number of favelas within but isolated in the city due to their lack of basic public services (water, sanitation, police, and fire protection), existence without legal tenure, and dependence on informal employment. The proliferation of favelas during Rio’s explosive growth and beyond had yielded to a city with some 23 percent of its population living in these areas in the late 20th century.

In the 1960s, as the favela populations “invaded” public and private land, the city and state embarked on forcible eviction, clearance, and relocation strategies. Between 1960 and 1973, the government removed some 175,000 people living in favelas (Bruma 2016), resettling them in newly laid out districts at the edge of the city. The City of God (“Cidade de Deus” or CDD), made world-famous due to an award-winning film based on it, is an example. Developed on a 175-acre site for some 3,000+ homes in 1965, the designers plotted a gridded street pattern with five-acre blocks accommodating 144 dwellings. Over the years, newcomers occupied vacant areas at the CDD’s periphery, and public services, especially policing, declined, resulting in the proliferation of drug-related crime and violence, making the “ideal” settlement notorious for its failure.

The city’s approach to favelas changed dramatically in the succeeding decades. Funded by some $ 600 million over thirteen years by loans from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and city funds, Rio embarked on the first phase of the FavelaBairro project (1994-2000) in 88 favelas, installing infrastructure (water, sewer, lighting), advancing public services (health, garbage collection, and education) and building recreational spaces while incorporating significant resident participation in all operations (IDB 1999; Cabral 2014).

In the second phase (2000-2008), the city focused on 70 favelas, continuing the infrastructure work and adding employment training for youth and adults, slope protection, and reforestation (Libertun de Duren and Rivas 2020). All observers viewed this upgrading program as successful in the near term (Gewertz 2000). However, a later evaluation reported deterioration in the services, leading to queries about whether the program’s expense ($ 4,000/per household) yielded sufficient benefits (Libertun de Duren and Rivas 2021). Others held that reasons for the decline could be found in population growth (between 2000–2010 favela population increased 24 percent while the city grew 3.4 percent), lack of maintenance on the part of the city and residents, and vandalism and crime, not program deficiencies (Libertun de Duren and Rivas 2020).

The city initiated a third upgrading program with IDB in 2010, renamed the Popular Settlement Urbanization Program which continued along the same lines as the Favela-Bairro project—$ 300 million divided between the IDB loan and city revenues. Its 2020 closing assessment reported that 9,000 households received title to their land through the program (IDB 2020).

In 2008, the state joined the city in addressing favela issues, focusing on crime. In preparation for the 2016 Olympics, it initiated a policing program called UPP (“Programa de Unidade Pacificadora”), covering 196 favelas inhabited by some 700,000 people (Azzi 2020). Under the program, labeled “proximity policing,” high-security police forces first cleared a favela of drug gangs then a second force followed to establish permanent stations. Between 2008 and 2016, the program, although controversial, resulted in a 27 percent reduction in homicides as well as decreases in thefts (Azzi 2020).

When updating the city’s master plan in 2023, Rio introduced two new elements: dedicating a chapter to favelas and including a section on community land trusts (CLT), a provision that allows a non-profit organization to own, develop, and manage land for affordable housing and associated services, keeping title in perpetuity (Papamanousakis and Fidalgo 2024). The innovative CLT concept requires complicated approval processes and, as yet, has not been tested.

Rio as an In-Demand Global Center

While many observers point to Rio’s hosting of the FIFA World Cup (2014) and Olympics (2016) as the turning points that made the city a global center so important that it would be the natural host for the G20, they are mistaken. Clearly, accommodating two major sports events was critically successful in demonstrating the city’s capacities, but Rio built this accomplishment on a strong earlier record of holding multiple and varied visitor-attracting events in addition to sports.

Among them were UN-based international meetings, religious pilgrimages, massive rock concerts, Carnaval, and emerging new economy convenings as listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Rio Hosts Global Events

Source: Author.

*Representative of several massive concerts.

** Emblematic of public space dedicated to the annual four-day festival.

*** An example of the many trade events that showcase the city’s new economies; Web Summit 2023 in Rio was the first one held in Latin America.

**** Rock in Rio has occurred every two years since its founding in 1985 (with a hiatus during the COVID-19 pandemic).

Perhaps Rio’s hosting of the FIFA World Cup in 1950 was the inspiration for the city’s late 20th-century reinvention policy focusing on sports. For Brasil, the event represented more than sponsoring a competition. The country that had joined the Allies in World War Two was ready to claim a more important position in global affairs. Thus, the 1950 World Cup would serve as a platform for not only being the first match since 1938 but also being a means for the country to be perceived as an important world leader (Merlo 2015). Accordingly, the state built the world’s largest stadium, the Maracanã, accommodating 200,000 spectators. [2]

In the early 1990s, Rio’s leaders seriously considered bidding for the Olympics. They studied how Barcelona had used the 1992 Olympics to reinvent their city and formed a multilevel bid committee that hoped to emulate the Spanish experience. However, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) thought otherwise, turning down Rio’s two bids in 1995–96 and again in 2003–2004. Not to be defeated, Rio set about showing the IOC that it was up to the job by securing the Pan American Games for 2007.

They used the Pan American Games to demonstrate Rio’s facilities and capacity to handle large events—the games brought 5,600 athletes from 42 countries to compete in 38 sports. Rio sized the sports facilities built for the 2007 games according to Olympic standards. When submitting what would be a successful bid in 2009, the city promised to use the Olympics to transform key infrastructure and public facilities as Barcelona had. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva attended the decisive IOC meeting, guaranteeing national financial support—some $ 17 billion for transportation improvements. The state also chipped in several million dollars as the city outlined its plans to improve several existing facilities as well as build new ones and provide transportation for the anticipated crowds (Silvestre 2012). In 2011, to demonstrate progress, Rio hosted the Military Games accommodating nearly 5,000 competitors who came from 108 countries to participate in 20 sports.

As the recently released Legacy of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games: Economic Impacts (Da Mata and Sampaio 2024) reported, the city fulfilled many of its promises to the IOC. The improvements included the Porto Maravilha regeneration project described earlier. They also encompassed major investments in transportation (e.g. Metro line 4, BRT expansion and greening, roads and tunnels), water (e.g. Seropédica Waste Treatment Center, environmental recovery of Guanabara Bay, Jacarepaguá Basin, and Lagoon Complex), and in athletic facilities, living arrangements, and associated cultural and educational legacy projects (e.g. Olympic Park and Village, the Sambódromo). Rio welcomed some 7.5 million people to the city itself while many more witnessed the events via television—some 2.5 billion people watched the opening ceremony (IOC 2017), a phenomenon that reinforced the city’s reputation around the world.

Beyond the Olympics, Rio hosted other visitor-attracting events to reinforce its claim to be an in-demand global center. The UNsponsored 1992 Earth Summit and the 2012 Rio+20, which set the scene for today’s global climate change campaigns, are examples. At the 1992 conference, some 25,000 civil society advocates assembled in forums in central Rio locales like Flamengo Park while the officials met farther away in Riocentro, the city’s convention center built in 1977 and renovated for the 2016 Olympics. Twenty years later, Rio+20 had become a megaconference. The 190 official delegates still met in Riocentro, but 45–50,000 civil society attendees participated in the People’s Summit, the Business Action for Sustainable Development Conference, 4,000 side events (only 500 at Riocentro) and/or marched through Rio’s downtown streets in one of 23 demonstrations (Ivanova 2013).

Other events in the roster before and after the Olympics include UN Habitat’s Fifth World Urban Forum (2010) which brought 15,000 urbanists to meet in re-conditioned warehouses in the port district; the World Youth Day in 2013 that attracted 320,000 young Catholics to the city and culminated in a mass celebrated by Pope Francis on Copacabana Beach before an estimated three million attendees (Ottaro 2013). And in the popular music world, Rio has been the home of Rock in Rio, a four-day concert spree held biennially since 1985. The September 2024 edition attracted 700,000 attendees. Further, the famed four-day Carnaval that plays out throughout the city attracted some two million spectators and participants in 2024, and trade shows like the Web Summit whose organizers picked Rio as a “tech-hot” city joining Hong Kong, Dublin, Doha, and Toronto, assembled 35,000 attendees for its meeting in April 2024.

Not to be forgotten on the account of Rio’s being a global center is its participation in the business side of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), the world’s 7th largest economy in 2024. While São Paulo dominates as a general business center, Rio nevertheless plays a critical role by serving as headquarters for some of the country’s highest-value companies. Vale ($ 90 billion in assets, a multinational mining conglomerate) and Petrobras ($ 202 billion in revenues, an energy business) are headquartered in the city (along with Shell, Chevron, and Total). Rio is also the headquarters of Grupo Global, Latin America’s largest media company. Of note, the headquarters function of the mining interests has grown recently due to Brasil’s huge supply of critical minerals (lithium, nickel, graphite, manganese, copper, and niobium) needed for the energy transition (Vásquez 2024).

Finally, Rio’s leaders have created specialized educational and industrial districts that have supported the city’s reinvention. Home to nine top public and private universities, the 69,000-student body Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), whose main campus is on the landfilled Ilha do Fundão (1948–51), is an example of the type of the high performing research institution with associated technology parks found in the world’s global centers. Further, Rio’s research centers account for 17 percent of the country’s scientific output (World Bank 2022, 5).

Rio has concentrated on an important industry in the Santa Cruz industrial district. This is the home of the Ternium steel company (founded in 2010, formerly the ThyssenKrupp Companhia Siderúrgica do Atlântico [TKCSA]) that produces five million tons of steel plate annually. It employs 8,000 people and has its own combined heat-to-energy power plant and its own deep-water port. While it has had a troubled environmental history, in March 2024, its Luxembourg owners announced the inauguration of a small year-long industrial symbiosis project in partnership with the Danish Kalundborg Symbiosis, Rio’s Greenova Hub, and Aedin, the industrial districts business association (CREA 2024; Aedin 2024). The area is so important that it merited a campaign visit by current mayor Eduardo Paes in August 2024.

An important aspect in this account of Rio’s positioning is how it plays into Brasil’s historic and ongoing quest for recognition as a global leader. Brasil has long sought representation in the world’s formal organizations—the United Nations (UN), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Bank, but these efforts have not come to fruition. However, Brasil has gained traction in informal organizations—the BRICS and G20, as indicated by its leading role in the BRICs, assuming the BRICS presidency in 2025 and hosting the G20 in 2024 (Stuenkel 2022). This success in the informal areas has secured other leadership positions for Brasil, including hosting the Clean Energy Ministerial (October 2024) and COP30 (2025).

When Rio grabs the world’s attention through its various convenings, it heightens Brasil’s global reputation.

Innovative Governance and Finance

Leading the reinvention of a city of more than six million demands vision, responsive governance, efficient management, and sophisticated financial expertise. Brasil’s 1988 Constitution provided the enabling environment that, in the 1990s through the first decades of the 2000s, allowed Rio’s talented leaders, especially its nimble mayors, to employ and enhance municipal planning and budgetary power. They have been able to engage multilevel government support and work with civil society and private sector partnerships at home and around the globe to target, execute, and operate critical investments in the country’s and the city’s challenging economic and political environment.

Three interrelated illustrations of the city’s agility in connecting policy, programs, and finance effectively underline the leaders’ intentional reinvention of Rio, living up to its name as the Cidade Maravilhosa. They are financing the Porto Maravilha regeneration project (2009 to present), creating the Operations Center (2010 to present), and implementing the climate action plan (2021 to present). They encompass activities related to hosting the first South American Olympics (2016) and to those taking place in the post-Olympic/post-COVID-19 period (2021). In little more than a decade, the city transferred its attention from accommodating 7.5 million athletes and tourists to dealing with epidemic-caused financial stress and climate change. These efforts, built on the important but fragmented work of previous decades described earlier in this chapter, have enabled Mayor Eduardo Paes to make the marvelous city more marvelous through dexterity, acumen, and imagination.

Financing the Porto Maravilha Regeneration Project

To implement the Porto Maravilha regeneration project, the city developed administrative structures and innovative financial instruments. It created an Urban Consortium Operation (UCO) establishing development rights (or Certificates of Additional Construction [CEPACs]) whose proceeds had to be used for regeneration. The city also established the Companhia de Desenvolvimento Urbana da Região do Porto do Rio de Janeiro (CDURP)—recently renamed Companhia Carioca de Parcerias e Investimentos (CCPar)—a special purpose vehicle, responsible for overseeing the CEPACs sales and engaging in public-private partnerships (PPP) for the execution of projects. Between 2011 and 2013 CDURP raised nearly $ 2 billion through the CEPACs auctions (World Bank 2020; Silvestre 2022), a sum that allowed the city to complete 85 percent of its planned infrastructure investments by 2016 (World Bank 2020). And, in less than a decade, developers who purchased the CEPACs had built some 2,089,963 square feet of Class A office buildings. CCPar also auctioned off a derelict gas storage site to Flamengo, one of the football clubs of the city, for a new stadium to be developed by 2029. Moreover, plans were in the works to market a section of the area as “Maravalley” (a play on the US’s Silicon Valley) intended to attract the tech industry as well as provide space for an undergraduate degree program offered by Rio’s highly regarded Institute of Pure and Applied Mathematics (IMPA) (SiiLA News 2023; Rial 2024).

As the regeneration program pursued its goal of connecting the port and downtown, the city instituted Reviver Centro, a tax relief and development rights program to encourage residential development in the center. Not only does the program provide multi-year exemptions from several real estate taxes, but it also permits developers who convert or build residential to construct the same amount for market housing or 150 percent of the total for social housing in other designated areas of the city. Due to the various incentives, private developers are finding the center and Porto Maravilha region attractive. Valor, Rio’s business journal, reported that three important firms, AVO, Cury, and Encamp expected to build 10,200 new units in the next two years.

Creating the Operations Center

In April 2010, Rio faced a huge storm that dropped 11 inches of rain in 24 hours wreaking havoc in the city: massive landslides killing 250 and displacing 10,000 displaced people; disabled transportation infrastructure; a collapsed emergency response system; and millions of reals (BRL) in damages. Rio’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, was mad and frustrated at the management breakdown. However, at that time, Rio was a participant in IBM’s Smarter Cities Challenge with its half million dollars of digital improvement consulting work. The city had already created a chief digital officer position and was poised to have a workshop on additional recommendations when the storm broke (Singer 2012; Freitas and Nogueira 2021). Paes immediately called on IBM to help address the city’s management and communications problems. He asked them to develop some sort of multipurpose center—one that could not only have an early warning system but also coordinate the city’s responses to large events, incidents, emergencies, and crises.

Taking up the challenge, IBM oversaw the creation of the Operations Center, assembling CISCO, Samsung, and local providers on a platform that integrated incoming data (such as phone, text, radio, and email) on flooding and traffic and dispersed the information to the responsible units of the 30 participating city agencies. COR (as in “Centro de Operações da Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro”) opened in December 2010—eight months after the landslide disaster—equipped with a system to predict storms, the capacity to manage large events (e.g. Carnaval with more than 450 samba parades and 350 sites whose routes could be scheduled and mapped with security and clean-up programmed) or respond to a wide variety of crises (e.g. dealing with a collapsed building or managing COVID-19 policies needing services from the fire, police, health and/or transportation agencies).

The results were measurable: within the first year, it developed the capacity to predict heavy rains 48 hours in advance, and traffic incidents fell 30 percent, illustrating a mayoral management style placing the city a leader in global innovation recognized by Rio’s receiving the Smart Cities Award in 2013 (EBRD 2021). Over time, Rio changed partners including moving to NASA, the US space agency for storm prediction, Google’s WAZE for traffic, and social media for citizen warnings. Costing $14 million ($ 20 million in 2024), the COR received worldwide press attention, drawing visits from some 10,000 city managers between 2011–2016, eager to replicate it. In 2023, building on its success, the city supported COR expansion, increasing the size of the situation room and resources for its resilience (COR 2022).

Implementing the Climate Action Plan

Rio is vulnerable to the full range of difficulties caused by global warming: sea level rise, flooding, extreme heat, drought, and landslides, as well as such associated problems as disease and displacement. The city has suffered particularly in the realm of heavy rain-caused landslides that have caused hundreds of deaths and massive displacement of favela households over time.

Memorable tragedies occurring in 1966 and 1967, 1988, 1996, 2010, and 2019, led municipal officials first to address a given disaster and later to stimulate the comprehensive mitigation and adaptation policies that have placed the city as a leader in innovative climate action around the world (Benmergui and Gonçalves 2019; C40 2015).

From the 1960s to 2000, the city engaged in preventive infrastructure investment through the Geotechnical Institute (founded in 1966) to undertake shoring up projects in hilly favela neighborhoods (Barbosa and Coates 2021). However, the 2010 landslide that stimulated COR’s creation would push Mayor Eduardo Paes to engage more broadly with climate change. Some link his dedicated leadership to this topic to his vision to make Rio a global center while others see it as part of the broader management reforms he carried out upon taking office, ones that resulted in tripling the

municipal budget or his engagement with other global city mayors from C40 (which he chaired from 2013–2016) that made him a spokesperson for climate change agendas (Mendes 2022).

Regardless of the motivation, Paes sustained a strong climate action program during his mayoralties (2008–2016) and (2020– 2024). In the first eight years, he developed the foundation for the city’s climate strategy through a series of laws, plans, and programs. They included the 2011 passage of Municipal Law 5248, mandating the city inventory its greenhouse gas emissions every four years; a series of three-year strategic plans (2009–2011, 2011–2013, 2013–2016) with detailed measures and indicators related to climate change subject to triennial evaluation and report of percent of targets reached; revision of the city’s master plan (2011); work with the World Bank on Rio’s Low Carbon Development Program (2012) to certify that Rio’s GHG remission measurements conform to the world standards (2013); collaboration with the University of Rio de Janeiro on a study, “Technical Assessment and Support of the Development of a Climate Adaptation Plan for the City of Rio de Janeiro (2013), that led to the Climate Adaptation Strategy for the City of Rio de Janeiro (2016); acceptance into the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities program (2014); and subsequent publication of Rio Resilient (2015), the first resilience plan in Latin America, overseeing the launch of the C40 City Climate Finance Facility (2015) at the Local Leaders Summit hosted on the sidelines of COP21 Paris and fostering the Plan for Vision Rio 500 (2016). Alongside these efforts, he aligned many of the Olympic programs with a climate agenda, especially the infrastructure investments in transportation.