When planned and managed sustainably and equitably, cities are engines of prosperity. In fact, cities contribute 70 percent of the world’s GDP. Yet, in many ways, cities have come to define and shape the overarching challenges of the 21st century: the speed and scale of their development is unprecedented. And housing the majority of the global population, cities are defining our world in new ways every day, raising complex questions about how to address the changes they bring to communities around the world.

With this in mind, and in conjunction with Penn's theme "Year of Why," we asked nearly a dozen urban experts, “Why cities?” In particular, we asked them to reflect on any or all of the following questions:

Cities throughout the world are growing in population and expanding in size—why is this? What are the most critical forces that are driving the new importance of urban centrality? How do they differ across the globe? How will urbanization impact inclusivity and sustainability? What are the common forces in global urbanization trends? How long will these trends last?

Their answers point to the centrality of cities in the future of our planet and its inhabitants, and shed light on how we can come to better understand and shape urbanization in the future.

--Eugenie Birch and Susan Wachter, Co-Directors, Penn Institute for Urban Research

Why Cities?

Urbanization: Now a Developing Country Phenomenon | Solly Angel

Can We Implement Changes Fast Enough? | Ani Dasgupta

Why Cities and What to Do about Them? | Gilles Duranton

The Rise of the City-State | Richard Florida

Proximity: More Valuable than Ever | Edward Glaeser

A Striking Reversal for Center Cities | Jessie Handbury

The Evolution of Urban Institutions | Bruce Katz

The Promise of Urban Models that are not Taxpayer Financed | Luise Noring

Urban Investment Must Keep Pace with Growth | Joseph Parilla

Addressing Urban Needs While Caring for the Land | Saskia Sassen

For Cities to Thrive So Too Must Globalization | Mark Zandi

by Solly Angel

Over the course of human history, a relatively small share of the population of our planet has lived in cities. That small share did not typically exceed 10 percent until the beginning of the Industrial Revolution circa 1800. The movement of the population into cities since then has increased rapidly, reaching a milestone in the year 2000, when half of the world's population officially lived in cities. This movement from country to city is what I refer to as The Urbanization Project, a project motivated by the conviction most of us share that the advantages of being closer to other people exceed the advantages of being closer to the land. While the world continues to urbanize, urbanization rates are now slowing down in all continents. By the end of the century The Urbanization Project will, by and large, be over. Most people who would have wanted to move to cities will have moved by then, and the world will be some 75-80 percent urbanized.

In some continents--North America, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean— urbanization is almost over already. Most urbanization between now and 2050 will take place in Sub-Saharan Africa (33 percent of the total) and in the Indian subcontinent (25 percent of the total). The rest will take place in China, Southeast Asia, West Asia and North Africa. All in all, 18 persons will be added to the urban populations of cities in less-developed countries for every single person added to the urban populations of the more developed ones. Urbanization is now, by and large, a developing country phenomenon. This is where our efforts at ensuring that it takes place in an orderly manner, so that it enhances productivity, inclusiveness, sustainability and resilience, must take place.

Solly Angel is Solly Angel is Program Director of Urban Expansion and Professor of City Planning at NYU’s Marron Institute of Urban Management.

Can We Implement Changes Fast Enough?

by Ani Dasgupta

No global development goal can be accomplished today without figuring out how to build more sustainable, more equitable cities. Most people already live in cities, and by 2050, perhaps as many as 7 billion out of 10 billion people on Earth will live in urban areas. Their productivity, their quality of life and their carbon footprints will depend on what kind of cities we build.

This new generation of urbanization will not be the same as the last. Ninety percent of new urban-dwellers will be in Africa and Asia. These cities will have fewer resources per capita and they are more likely to be regional or local hubs, rather than megacities.

Economic growth is not accommodating urbanization in the same way it has in the past either. Even as overall poverty declines, the share of poor people living in urban areas is on the rise. Nearly 900 million people live in slums today without access to basic services like water, sanitation and housing. If current patterns of urban growth continue, the number of slum dwellers will reach 1.2 billion by 2050.

Other trends are also headed in the wrong direction. The amount of land being used for urban purposes is expected to triple between 2000 and 2050, leading to the loss of natural ecosystems and agricultural land. Meanwhile, to stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius of global warming, emissions from buildings must be reduced 80-90 percent by mid-century and all new construction must be “fossil-free and near-zero energy” in just two years.

These are huge challenges, but they also represent opportunities. Cities are factories of innovation, consistently generating new solutions to big problems. Some 75 percent of the infrastructure expected to be in place by 2050 has yet to be built, and most will be in cities. Research shows more compact, more connected cities can generate compounding dividends for people and the planet, for example. The net value of low-carbon urban investments is estimated at $16.6 trillion by 2050.

The question in front of us is whether we can implement changes fast enough. A window for transformation is opening, and it’s up to us to seize it. Cities are the best chance we have to get this right.

Aniruddha Dasgupta is Global Director at the World Resources Institute’s Ross Center For Sustainable Cities.

Why Cities and What to Do about Them?

by Gilles Duranton

Cities offer sizeable economic benefits. First, they make firms and workers more productive through a variety of agglomeration effects. Recent research estimates that a city with a 10 percent greater population is 0.2 to 0.5 percent more productive. While this may not sound like much, we need to keep in mind that large cities are much larger than small towns. In the US, agglomeration benefits in production imply that, to the same workers, the likes of New York or LA will offer wages 50 percent or so larger than a city of 10,000 inhabitants. In addition, cities allow their residents to consume a much greater variety of goods and amenities at prices that are no higher, and often lower, than in small towns. A good case can be made that these consumption benefits of large cities may be as large as their productive advantage in terms of jobs and wages. It has also been shown that larger cities allow workers to accumulate more knowledge and a more valuable experience in the long run. Again, the best available evidence suggests that the learning benefits of cities are of the same magnitude as the productivity advantages mentioned above. Bottom line: Our GDP and our standards of living would be considerably lower in a counterfactual America that would be entirely rural.

At the same time, cities are also costly places to live, particularly the more successful ones. American households devote nearly 50 percent of their expenditure to housing and transportation. Competition for land in larger and denser cities is fierce. This leads to higher housing costs on built-up land and slower and more congested mobility on open roads. Much of the agglomeration benefits of cities are thus lost in traffic jams and expensive housing.

Improving cities may mean increasing their benefits or reducing their costs. From the promotion of high-tech clusters to many local economic development initiatives, many development policies aim at fostering agglomeration benefits. Truth be told, we know very little about how agglomeration effects work. We can measure the benefits from agglomeration. However, we do not really know how they percolate. Thus, we have no clear idea about how to expand and promote these agglomeration benefits.

On the other hand, much can be done to reduce the costs of cities. While some of the costs of crowding more people together are unavoidable, we make our most prosperous cities unduly expensive. Property development is overly restrictive. The built-up housing stock of highly productive places like San Francisco or Boston increases by 0.5 percent per year or less. This is an order of magnitude less than the 4 to 5 percent per year that less productive and desirable cities like Houston or Phoenix have reached in the past. Worse, the little construction that happens in more restrictive cities is often sub-optimally dense and highly spread-out. Improvement in mobility and accessibility are also dearly needed. While there is no obvious silver bullet for transportation policies, two changes need to happen in urban transportation policy. First, “all or nothing policies” such as “everything for the car” or the “war on cars” are unproductive. Mobility needs to rely on a portfolio of options to be effective. In addition, being able to go places is not only about mobility. It is also about proximity and the combination of the two forms accessibility. Better accessibility requires a much better coordination between transportation and land use planning.

Gilles Duranton is Dean’s Chair in Real Estate, Professor, and Chair of the Real Estate Department at the Wharton School.

by Richard Florida

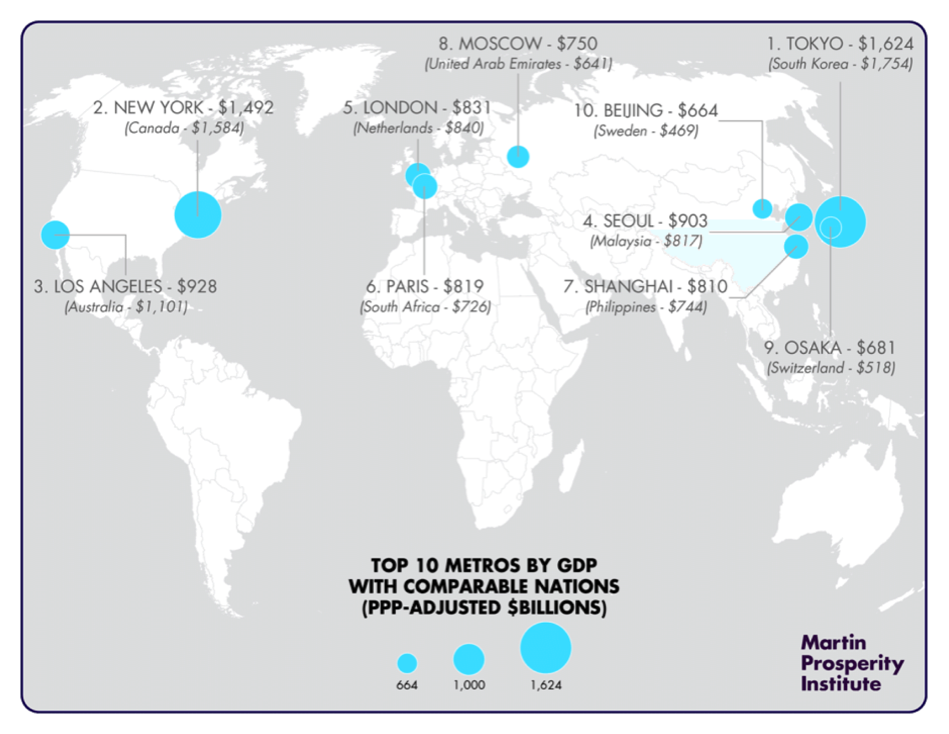

The world is shifting from a system organized around nation-states to one that revolves around cities and metro regions. Across the globe, nation-states are looking backward—electing populist leaders who want to set back the clock on economic, social, and cultural advancement. Our cities are the true drivers of global economy. The world’s 300 largest metropolitan areas produce nearly half of the world’s economic output, despite hosting just 20 percent of the world’s population. The largest, most productive metros are as economically powerful as major countries, as the map below shows.

In too many parts of the world, cities remain beholden to backward looking nation-states - trapped by political regimes that actively try to undermine their economic and cultural assets, siphoning off their tax revenues, under-investing in their infrastructure, undercutting their investments in universities and innovation, and pre-empting their abilities to attract immigrants and remain culturally open and tolerant.

In too many parts of the world, cities remain beholden to backward looking nation-states - trapped by political regimes that actively try to undermine their economic and cultural assets, siphoning off their tax revenues, under-investing in their infrastructure, undercutting their investments in universities and innovation, and pre-empting their abilities to attract immigrants and remain culturally open and tolerant.

In her final book, the late great urbanist Jane Jacobs correctly surmised that we will face a deepening “Dark Age Ahead” and that the last great hope for democratic life lay in our cities and communities. Localized government is more economically efficient and democratic than the centralized alternative. And surveys demonstrate that citizens have more confidence in local government than national government. Our cities remain the true beacons of progress and compassion, developing new approaches to equity and inclusion, devising new initiatives on jobs, healthcare and education.

Our global future requires a shift in political and fiscal power commensurate to the shift in economic power from the dysfunctional nation-state to cities.

Richard Florida is University Professor and Director of Cities at the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, Distinguished Visiting Fellow at NYU’s Shack Institute of Real Estate, and the co-founder and editor-at-large of The Atlantic’s CityLab. He is author of The Rise of the Creative Class and most recently of The New Urban Crisis.

Proximity: More Valuable than Ever

by Edward Glaeser

The United Nations reported that the global urbanization rate increased to 55 percent in 2018, which means that the world has over 4.2 billion urbanites. More than 3.2 billion of those city-dwellers live in “less developed regions,” and over 420 million live in sub-Saharan Africa. While scholars can seriously debate these numbers, especially given the unclear definition of the word “urban”, there can be no debate that cities have expanded massively over the last 30 years, especially in the developing world.

The fundamental advantage brought by urban density today is proximity to other people, which enables the exchange of goods and services and the free flow of ideas. That urban advantage also existed in Pericles’ Athens and Maimonides’ Cordoba, but several factors have made proximity more valuable than ever, especially in the developing world.

Globally connected cities enable poor people to trade with the outside world, which is particularly valuable when parts of the outside world are very rich and much of the local hinterland is very poor. This urban advantage is particularly stark in China, where coastal trading cities, like Shenzhen, teem with BMWs and Audis, but rural China often remains remarkably poor. Can we wonder why so many Africans leave the poverty-stricken world of subsistence agriculture to find a place in global cities like Lagos and Johannesburg?

Until World War II, urbanization generally followed rural prosperity, because cities would starve without large food surpluses. Globalization and technological change have made it far easier for poor countries to feed large urban populations, by importing either food or agricultural technology, as in the Green Revolution. Freedom from fear of starvation has enabled vastly more poor people to come to cities.

Moreover, in the wealthy and poor world alike, cities have grown because skills and ideas have become more valuable. We are a social species that becomes smart by being around other smart people. Cities— from Sao Paulo to Shenzhen to Seattle— are places where we acquire the skills to succeed in the global market for talent.

Naturally, massive urbanization creates challenges as well as opportunities. Density doesn’t just enable trade and spread ideas. Density also enables the spread of contagious diseases and crime and traffic congestion. Yet I am convinced that there is no future in rural poverty. The future will be urban. The great challenge is to ensure that the cities of the future will be more humane, healthier and more affordable.

Edward Glaeser is the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University.

by Jessie Handbury

The turn of the 21st century has seen a striking reversal in the fortunes of U.S. center cities. After decades of urban decline in the mid-20th century, wealth is now becoming more centralized in large U.S. cities, even though the population continues to suburbanize. As middle- and high-income households are moving into downtowns, lower income households are starting to suburbanize. These trends are at least in part the result of secular growth in top incomes and changes in household composition, both of which are increasing the taste of the very rich for non-tradable service amenities. The same economies of density that make these amenities abundant in urban cores imply that they will multiply in response to the changing composition of urban residents, making downtowns even more attractive for the wealthy.

Since top income growth and delayed marriage and childbirth rates are global trends that show no signs of abating, cities worldwide are already or will at some point see these same forces take hold, shifting the sorting behavior of the wealthy into downtowns and the poor into smaller urban residences or out of downtowns altogether. It will be important to understand the welfare consequences of this sorting behavior and, in particular, reduced affordability of urban housing and services for low-income households as the tastes of the rich continue to reorient towards dense locations in the coming decades.

Jessie Handbury is Assistant Professor of Real Estate at The Wharton School.

The Evolution of Urban Institutions

by Bruce Katz

The rise of cities as the principal form of human settlement is driven by multiple forces, principally (1) the global economy’s demand for the agglomeration and concentration of assets in defined geographies at the metropolitan and district level and (2) the ubiquitous desire of individuals and families in different societies to gain economic opportunity and social mobility. The universal question is not whether cities will grow but how cities maximize the inclusive and sustainable outcomes of the growth that occurs.

The challenge: cities across the world inherit instruments and institutions which are anachronistic in form and structure, driven more by the dictates of higher levels of government and global financial institutions than by the needs and priorities of cities themselves. Driving inclusive and sustainable growth will require the invention of new instruments and institutions that are built by cities for cities and then adapted across the world to communities with radically different legal systems, governance structures and economic starting points.

Some of these institutions, like the Copenhagen City & Port Development Corporation, enable a virtuous cycle of large-scale sustainable transformation of core urban areas that creates and then captures value for long-term investment in infrastructure. Other institutions, like the Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation, enlist private and civic capital to drive large-scale neighborhood regeneration that is truly inclusive. Still other intermediaries, like Sweden’s Kommuninvest or C-40, enable cities within a nation or across the world to exercise their collective market power and negotiate with financial institutions and technology companies for smart practices and instruments.

An Urban Age, in short, requires the evolution of urban instruments and institutions that can harness large pools of capital and deploy innovative mechanisms for building resilient communities and making markets that work for disadvantaged people and places.

Bruce Katz is the Director of the Drexel University Nowak Metro Finance Lab. These views reflect research conducted in collaboration with Professor Luise Noring of Copenhagen Business School.

The Promise of Urban Models that are not Taxpayer Financed

by Luise Noring

The central question posed in this commentary concerns cities, and the cause and effect of globalization on cities. Due to a multitude of circumstances, we are pulling closer together. Distances are reduced. During recent years, mass migration has seen people from Africa and the Middle East moving to European cities and people from Latin America moving to U.S. cities. In Western Europe, when people migrate, they move to cities, as agricultural production automation leaves rural dwellers unemployed. All over the world, people move to cities that grow at a faster rate than rural populations.

As the world is becoming “smaller”, cities are confronted with common challenges of how to accommodate and provide job opportunities, decent livelihoods, education, health, etc. for growing and diverse populations. We may ask ourselves if there are shared solutions to the common challenges faced by cities across the world. Instead of every city trying to find the way and means to provide affordable and social housing, large-scale public transit, and renewable energy, for example, we can source the best city solutions from across the world.

Yet, the problem is that cities have very different political and economic inclinations. For instance, in Vienna, Austria, the city provides up to 40 percent affordable housing for its citizens, disrupting the private housing market and preventing Vienna from competing globally for property investments and developments. At the other end of the continuum, New York City just purchased the second headquarters of Amazon for 1.3 billion USD, disrupting what should be a level playing field for all businesses, including smaller tax paying businesses, to compete on. When one corporation is granted large tax subsidies, it prevents other local, national and international firms from competing on equal terms and conditions.

Both these examples illustrate how taxpayer money is spent in two radically different ways, reflecting different political and economic priorities. As such, we might term the Austrian model “citizen welfare” and the U.S. model “corporate welfare”. The challenge is that both models rely heavily on taxpayers subsidizing certain segments of the population (i.e. population groups, large corporations). The solution lies in identifying and codifying models that are not financed by taxes. Such successful models exist across the world. For instance, in Copenhagen, national and local governments have managed to turn around the city in just two decades from unemployment rates of 17.5 percent and an annual budgetary deficit of 750 million USD to one of the wealthiest cities in the world. This was accomplished by identifying and leveraging public land assets that were underutilized due to the large-scale deindustrialization that had led to the mass unemployment in the first place. Instead of trying to do more of the same, national and local governments repurposed its assets in reflection of a new urban era. In the process, they financed the construction of a cross-city state-of-the-art metro system. Similarly, 20 percent of the Danish population lives in affordable and social housing, yet they self-finance their dwellings. This is done so successfully that the residents take pride in their dwellings, while the industry accumulates vast savings and investment capital for further housing expansion, social activities, building improvements and maintenance.

As these models, and many others (read: https://www.cityfinancelab.net/volunteer/) do not rely on taxpayer money and are self-governed, they should indeed be “easy” to adapt to cities elsewhere in the world. Yet, that would require cities to shift away from existing deeply ingrained beliefs, including those supporting “citizen welfare” and “corporate welfare” models.

Luise Noring is Research Director at Copenhagen Business School in Denmark. To read more about her work, visit www.luisenoring.com, www.cityfinancelab.net, and www.cityfacilitators.com.

Urban Investment Must Keep Pace with Growth

by Joseph Parilla

The world is becoming more urban, placing cities at the center of global economic development. The share of global population in metropolitan areas has grown from 29 percent in 1950 to well over half today, and it is predicted to reach 66 percent by mid-century.

Why? History indicates that urbanization both accompanies and facilitates economic transition from agriculture to manufacturing and services, activities that tend to demand clusters of labor and capital as well as the proximity to other firms that cities provide. Urbanization and industrialization, therefore, tend to occur in concert, although the link is not preordained. These twin forces, which revolutionized Europe and North America in the late 19th century and early 20th century, have now touched Asia and Latin America and are working their way through Africa.

Urbanization in developing economies has resulted in a much greater number of urban areas in which firms and workers can thrive. In technical terms, agglomeration externalities—the benefits that accrue to firms, workers, and local economies from clustering—now exist in many more parts of the world. As a result, the 50 percent of the world’s population that lives in urban areas produces roughly 80 percent of the world’s total output.

Urbanization, however, comes with risks if it is unmanaged. Rapid population growth in the megacities of Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia are straining the ability of local governments to provide basic housing, transportation, energy, water, and sewage infrastructure. The world will need to invest $57 trillion in new infrastructure by 2030 to keep pace with expected growth. If the negative externalities of congestion, insecurity, and health risks overwhelm the positive externalities that cities provide, countries run the risk of urbanizing without increasing living standards.

Joseph Parilla is a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program.

Addressing Urban Needs While Caring for the Land

by Saskia Sassen

A close examination of why urban populations are mostly growing brings up two rather different factors. One is familiar: more people want to live in cities. The second one is less familiar and less self-evident: in a growing number of countries the rapid growth of cities is due to rural populations being expelled, often brutality, by the private armies of major landholders. Why? There are multiple and diverse reasons, but one major reason is that they are after more land. (See, for example, the case of Central American refugees driven by land grabs, and the case of land grabs driving the persecution of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar.) Why more land? One key reason is that plantation agriculture kills the land much faster than traditional agriculture so there is a constant search for more land.

This mix of corporate growth practices that kill land fast and the grabbing of land from small old-style farmers (who know how to keep the land alive for centuries), is in good part fed by the needs of cities for everything from foods to building materials.

But this is unsustainable at both ends: the plantation mode of growing food and our current urban mode of mostly not growing much food in our cities. There are cities in Europe that grow quite a bit of food, but this does not hold true for much of the rest of the world’s cities. There is also a growing range of urban “vertical farming” options that are emphasizing local food production; this is mostly confined to European cities for now. The outcome is an unsustainable tension between a) what cities need and b) the destructions of habitat that result from current modes of meeting those needs.

We need to extract multiplier effects from what we now have in cities and what we could bring into cities. For instance, let us take trees and plants in well-run cities. Far too many are decorative. Can we replace or add trees and plants that can also meet some of our needs, even if they are not the prettiest? “Attractive” is not enough. We need utility functions. If we multiply this small example into the hundreds and thousands of trees and plants with a strong “utility function”, we can begin to see how many small interventions can make a difference.

Land and water are dying at faster and faster rates across the world --in good part due to mining, chemically driven commercial agriculture, and the accelerating expansion of cities and slums in many parts of the world. All of these modes of growth need land, water, and the rocky terrain of mines, and they extract what they are after in full, or not so full, respect of the law, and even in modes that break all laws. There are now over 30 major countries and over 150 multinational firms, many dutifully respecting the law, who have set up operations –mining, water extracting, and plantation agriculture—in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. These large-scale operations have expelled millions of traditional small landholders who knew how to keep the land alive for centuries. They are now increasingly slum dwellers, and we have lost their knowledge.

But we cannot give up. We have, in many a city, developed new types of knowledge and instruments to address urban needs in modes that ensure long lives of plants, trees, and food crops in both rural and urban settings.

Saskia Sassen is the Robert S. Lynd Professor of Sociology at Columbia University and a Member of its Committee on Global Thought, which she chaired till 2015. She is the author of several books including Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy and Cities in a World Economy, 5th Edition.

by Mark Zandi

Well over half the world’s population lives in urban areas, and if current trends continue, closer to two-thirds will a generation from now. The world’s urbanization has been long in the making, and in recent decades has been supercharged by economic globalization. Global trade, investment and immigration have surged, enhancing the advantages of cities, particularly those that are gateways to the rest of the world.

Global gateway cities are the beneficiaries of the infrastructure necessary to be part of a globalized economy. This includes sea and airports, rail and highways, and telecommunication networks. These cities are also financial centers, as global economic activity must be financed. Urban areas are also empowered by the increasing importance of global supply chains that require scale and thus a large workforce.

To compete in a globalized economy, businesses need a highly diverse and inclusive workforce. Understanding and being sensitive to differences in culture, social norms and language are necessary to do business in other parts of the world. This will become even more important as the global economy shifts from being manufacturing-based to service-oriented. Only urban centers can satisfy the quality of life and lifestyle choices that a globalized workforce demands.

The more globally open a city, the greater its success and size. It’s no accident that truly global cities such as London, New York, Shanghai, Singapore, Sydney and Vancouver are flourishing. But for cities to continue thriving, so too must globalization. This is not a given in the age of Brexit and Trump.

Mark M. Zandi is chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, where he directs economic research. He is the author of Paying the Price: Ending the Great Recession and Beginning a New American Century and Financial Shock: A 360º Look at the Subprime Mortgage Implosion and How to Avoid the Next Financial Crisis.