In 1975, when I was an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania, I commandeered a large Deer Park water jug from somewhere on the campus. Every night, I’d empty my pockets and put the change in that jug, and after I graduated, wherever I moved, I always took that jug with me. By 1988, the water jug contained a fair amount of change. When I was first running for City Council in the 1987 election in Philadelphia, my car had died, and after I’d lost the election, I turned that jug upside down every day to get quarters so that I could scrape together the money to catch the SEPTA (Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority) bus and elevated train to work.

That was in 1988. Twenty years later, on January 7, 2008, I was standing on the stage at the Academy of Music at Broad and Locust Streets in Philadelphia, being sworn in as the ninety-eighth mayor of my hometown. The road was long, and there were many events and happenings in between. And I didn’t take the journey by myself.

This is a story, and a political autobiography, about commitment and perseverance, about the passion and desire to serve. If you enter the world of public service for the right reasons, it’s the most incredible feeling that you will ever have. You will never make a lot of money in public service. Most of the people who try to make money end up going to jail. But there is something entirely unique about the opportunity, every day, to make somebody else’s life better. It’s a feeling that you can perhaps get in some other professions, but I know that it happens in this one. I would contend that being the mayor is the best job in politics, and possibly the best job in America.

*****

Mayoring involves many paradoxes. Being mayor is a lonely business, and leadership of a city can be a very lonely place. At the end of the day, you’re the ultimate decision maker, at least within your realm. To be sure, there are external factors and influences in city government: there are other nearby local governments, and state and federal governments with which you have to build relationships and interact. Cities generally are a political subdivision of their respective states. There can be a lot of tension between and among cities and their respective states, and between states and the federal government, depending on the policies and programs that are being proposed at any given time. But, for the most part, cities are allowed to operate autonomously. Many have home rule, and as mayor you are pretty much out there on your own. As mayor, just about all the bucks do actually stop at your desk. That doesn’t necessarily mean, unfortunately, that the actual, financial bucks stop at your desk—but the problems, issues, and challenges all end up there. And, quite honestly, whether or not you have any control over the problems or issues in question, you’re the mayor, so it all becomes your responsibility on some level.

At the same time, the mayor’s office is the position that I believe is closest to the people and to their real lives and experiences. It’s unlikely that you’ll be able to chat on the streets with the president, a senator, or even a state legislator, but anyone in Philadelphia might have stopped me to talk at the supermarket or found me at Woody’s barbershop once every two weeks.

A lot of people depend on you on a daily basis. There is a weightiness to the mayor’s office. The other political offices are certainly weighty, as well—being governor is an incredible responsibility, as is being the president of the United States. But people are sometimes not entirely sure what the governor may be doing at any moment, and I don’t mean that disrespectfully toward the governor in any state. It’s just that the gubernatorial position is usually a little more removed and distant from the people. Most presidents, of course, look at Washington, DC, as the place where they function and operate—although apparently not President Trump. As I write this in 2017, we mostly know where the president is but rarely know what he’s doing. While some people consider both governor and president to be “higher” offices than mayor—and they are indisputably different offices—there is no office as close to the people as being in charge of a city. People understand intuitively the mayor’s position more than other political offices, so while it may at times feel lonely, it is also a much more visible one, and you are rarely alone. People know where you are, and usually want to be near you.

When you as a citizen wake up in the morning and turn on your faucet, you have started your daily relationship with your local government and the mayor. You have an expectation that water—and potable, clean water—will come out of that faucet. When you step outside, you expect that the streetlights and traffic signals will work. Your roads on your drive to work in the morning will be decently paved. When you put your trashcan out on your trash day, you expect that it will magically be emptied by the time you come home. When you call 911, you expect a trained, respectful operator will help you, and then a first responder will appear. When you take your children to a recreation center, there will be equipment such as basketballs and soccer nets, and in good condition. That is all city government. And that is the work of mayoring—an ongoing exchange between larger government policies, including the budgets that fund them, and a daily engagement with and in the lives of citizens.

As mayor, you can accomplish tangible things. I don’t know the party affiliations of many other mayors in my acquaintance, because the problems and issues that we share are all the same and are often very remote from party dicta or ideologies. When he was mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia famously said that “there is no Democratic or Republican way of cleaning the streets.” Being mayor is where politics hits the road—literally. You remove snow, pick up trash, deal with climate events, and repair potholes. It’s where the action is. But you can also apply your core values, principles, and vision to make a measurable improvement in your city and many communities.

During my eight years in office I learned another paradox in the work of mayoring. The buck stops with you, and it’s a singular experience in that regard, yet it’s a collective experience that you absolutely must do with a team of leaders and that absolutely involves communication across many different constituencies, neighborhoods, and audiences. When I look back on my mayoring years and at video clips from press conferences, I notice one striking thing: I am almost never, ever standing alone. I believe in “team.”

Being mayor is one elected position, but it’s not a singular operation. It may be a lonely experience, but you have to do it in concert with a host of other people to communicate a message that will resound across the city, region, and state.

One of the constant themes in the chapters that follow is the relationship between the concepts of leadership, communication, and community. Leadership is about bringing people together in shared values for various common goals. It’s about expanding the tent. You can only conduct the business of mayoring well if you communicate, support transparency, and create as big a tent for your constituents and goals as you can.

Public service is a trust, a gift, and it is an honor to serve, whether you are elected or selected. And, if you ask me, being mayor is the best job in America.

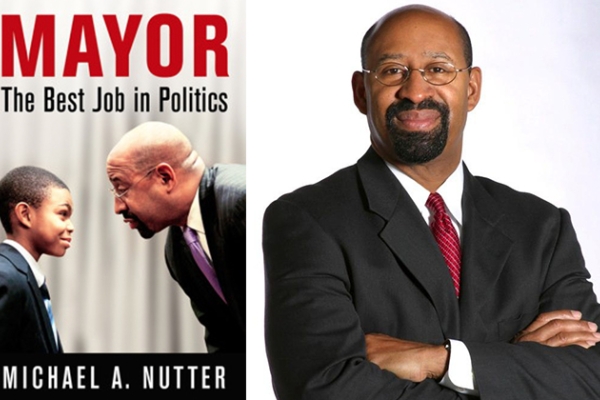

Michael A. Nutter was elected mayor of Philadelphia in 2007 and served two terms. He is now Senior School of Social Policy and Practice Fellow at Penn IUR and the David N. Dinkins Professor of Professional Practice in Urban and Public Affairs at Columbia University. The above article is excerpted with permission of The University of Pennsylvania Press from Nutter’s forthcoming book, Mayor: The Best Job in Politics. (All Rights Reserved, University of Pennsylvania Press, copyright 2017)