Introduction

Developing strategies that respond to increasing demands for affordable housing is a national challenge. Housing shortages are impacting both large and small communities, shaped by a range of underlying real estate market, public policy and capital access strategies that can impede, prevent, and/or slow progress towards the production and preservation of housing across the affordability spectrum. The trend towards increasing housing cost burden remains troubling—not only from a housing access and fairness lens, but also more broadly due to the key role that housing plays in more equitably distributed economic growth and competitiveness.

To reinforce the deep need for housing solutions, we turn to some recent data trends reported by the Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) in their 2023 State of the Nation’s Housing Report (2023). In the study, JCHS starkly highlighted a growing lack of access to homeownership for millions of American homeowners and renters, including two trends vital to understanding the need for scalable solutions (whether existing or new) to meet our affordable housing needs:

2.4 million renters were priced out of the home ownership market in 2022, as monthly all-in-costs (mortgage, insurance, and property tax) for a median-priced home in the U.S. reached $3,000 per month in March 2023. This included a disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic homebuyers.

In 2021, 19 million homeowners (22.7%) were cost burdened—the highest level since 2013. Nearly 9 million homeowners (10.4% of all homeowners) spent more than half their incomes on housing costs with an especially high burden on those earning less than $30,000 per year. Black, Hispanic, Asian, and older homeowners were also more likely to experience significant cost burdens.

In June 2023, Penn IUR and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy jointly convened a one-day roundtable on shared equity housing (SEH) as a solution for the increasing scarcity of affordable housing. The roundtable convened academic and practitioner leaders in housing and focused on the potential to address affordable housing challenges through scaling of SEH solutions, including:

new policy tools that federal, state and/or local jurisdictions can deploy;

land acquisition and assembly tactics; and

capital aggregation strategies needed to scale such solutions.

More than 20 stakeholders, including affordable housing leaders and providers, academics and scholars, and policy practitioners came together at the University of Pennsylvania to share their expertise.

Reference

Defining Shared Equity Housing Models

SEH models are mission-driven housing strategies that seek to leverage housing subsidies to (1) generate long-lasting affordable housing supply and (2) provide accessible wealth creation opportunities and pathways for community-based land ownership. The “shared equity” structure ensures housing subsidies remain with the unit, passing the affordability benefit on from one occupant to the next, rather than being solely absorbed by the initial homeowner (who claims the full benefit of a subsidized home when they subsequently sell the property at market prices). SEH, in effect, is an umbrella term that covers an array of specific tools.

Community land trusts (CLTs) are one of the most well known SEH models, built upon a nonprofit organization that stewards an inventory of subsidized homeownership (and sometimes rental) properties and income-qualified homeowners in perpetuity. CLTs, however, are often small in scope and can struggle to acquire properties in the current market context. More generally, SEH models may be a means to keep housing affordable in neighborhoods with rapidly appreciating housing prices.

In recent years, some organizations are pursuing adaptations on the CLT model, seeking to increase its scale. In the financing arena, Grounded Solutions Network (GSN) is launching an investment strategy that would enable CLTs to acquire market-rate properties and rent them for a period, recouping initial investment expenses, before transferring the properties into a traditional CLT format (more discussion below, Capital Fund for (future) SEH Acquisition). Meanwhile, “mixed income neighborhood trusts” (MINTs) offer an SEH-adjacent example. MINTs leverage a community-controlled, neighborhood-scale investment pool to acquire scatter-site rental properties. The rental portfolio is balanced to enable a smaller share of market-rate properties to subsidize rent stabilization of a larger share of units, minimizing displacement pressures within gentrifying neighborhoods. Launched as a pilot by Trust Neighborhoods, a national nonprofit that brings together capital and organizational resources, the MINT model has been enacted in two neighborhoods thus far (more discussion below, Mixed Income Neighborhood Trusts).

This summary report on the roundtable briefly contextualizes the shortfalls in existing models of subsidized affordable housing, with an emphasis on Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) projects as the largest federal program. Subsequently, it describes the contours of SEH strategies, broadly, and CLT programs, specifically. Lastly, the report introduces a few of the key challenges for CLTs and summarizes emergent innovations for the sector.

An Affordable Housing Crisis: Supply, Demand, and Gaps

The genesis for the roundtable rests in existing housing conditions, characterized by escalating housing costs and pressing demands for greater access to affordable housing across the U.S. It is widely accepted that the U.S. is facing an affordable housing crisis (National Low Income Housing Coalition 2023; Joint Center for Housing Studies 2023). This is true in the private housing sector, where speculative investors are increasingly crowding out homeowners in the single-family market and rents are rapidly appreciating. Critically, traditional affordable housing supplies via federally subsidized programs are also facing unmet demand and threats to supply. Approximately five million rental units are supported by federally funded, project-based housing programs, accounting for approximately 10 percent of the rental stock across the U.S. (Aurand et al. 2021). Within this landscape, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program (LIHTC) contributes nearly half of all federally supported affordable housing supplies (Aurand et al. 2021).

LIHTC projects are required to adhere to a 30-year affordability standard that ensures affordable rents for households earning, typically, between 30 percent and 60 percent of area median incomes (AMI) (Freddie Mac 2022). Since program inception in 1987, more than 40,000 projects have been produced via the LIHTC program, accounting for approximately 3 million units. According to studies by the NLIHC and the Public and Affordable Housing Research Corporation (PAHRC), nearly 750,000 federally assisted rental homes, across all program, are scheduled to lose their affordability restrictions by 2030, with LIHTC properties contributing the highest potential losses (Aurand et al. 2021).

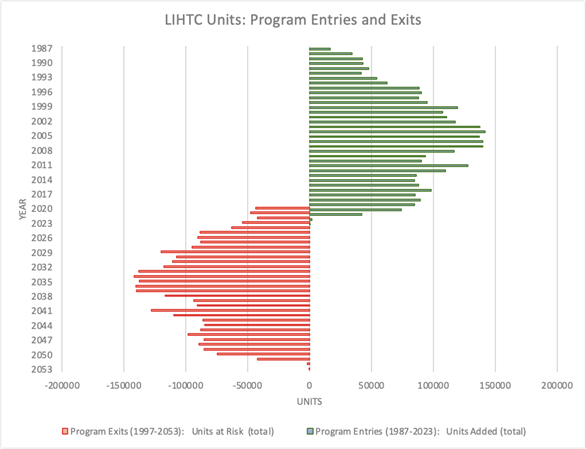

Relying on HUD-reported LIHTC data, there are nearly 41,500 active LIHTC projects with 3.1 million units. A substantial number of these units are at risk for exiting the LIHTC program and, thus, losing their affordability protections within the next 20 years. Existing data suggests 18 percent of existing LIHTC units (approximately 550,000 units in 9,300 projects) are eligible to leave the program between 2020 and 2029, with an additional 39 percent of existing affordable LIHTC units (approximately 1.2 million units in 14,700 units) facing expiring protections between 2030 and 2039. The rate of exit is linked to the pace and timing of entries into the LIHTC program, which has been slowing in recent years and does not meet “replacement” levels. In the 2000s, the program generated an average of 118,900 units per year (approximately 1.2 million units, total), but the average has decreased to 93,900 during the 2010s (938,600 units, total). As of 2023, the average pace in the 2020s is only 29,600 units (118,500 units, total). Figure 1 provides an illustration of impending exits and entries on an annual basis.

Figure 1. Estimated number of LIHTC unit entries and exits by year, 1987-2053 (HUD-reported LIHTC data)

Note: These are estimates based on the 30-year exit date. Some properties have already exited the program (either via qualified contracts at the 15-year mark or other means); other projects have insufficient data and could not be tabulated.

Source: Author with data from PolicyMap, 2023

There is also some variability in the timing of LIHTC expirations. Although LIHTC projects are subject to a 30-year affordability period, the IRS-enforced compliance period for developers is only 15 years with remaining enforcement mechanisms in years 15 to 30 varied by state (Caputo, Le, and Reidy 2023). As of year 15, there is a pathway for developers to sell the property and exit the program early via a Qualified Contract process (Freddie Mac 2022). The National Council of State Housing Agencies suggests that, as a result of this enforcement gap, more than 10,000 LIHTC units are lost annually after the 15-year window (Joint Center for Housing Studies 2022a).

Recent research by Freddie Mac assessed 134 “non-programmatic” LIHTC projects (i.e., projects that have exited the LIHTC program), finding that these units do tend to remain affordable relative to market rents (2022). There is variation based on the metropolitan area and local housing market context surrounding the project, but the median project still provides rents affordable to households making 60 percent AMI. However, none of the non-programmatic projects remained affordable to lower income levels indicating the critical risk of losing deeply affordable units in particular (Freddie Mac 2022). Data suggests that more than half of LIHTC residents earn 30 percent of AMI or less, revealing a substantial gap in affordability as LIHTC projects expire (Aurand 2022).

The Potential for Shared Equity Models to Respond to Affordable Housing Challenges

The tandem supply and demand pressures in housing markets have generated steep challenges for households seeking affordable housing options. The federal response to affordable housing has also reached a critical juncture, wherein existing LIHTC supplies—the largest contributor to federally supported affordable housing—are facing substantial losses over the next two decades and incoming units are falling short of a 1:1 replacement rate.

The contours of current housing needs and pressures call for innovative solutions. As an umbrella, SEH models offer a framework for addressing affordable housing challenges in lasting ways. This suite of mission-driven housing can provide several key advantages over existing affordable housing responses, including (but not limited to):

SEH programs are intended to provide permanently affordable housing, free of any time-limited affordability clauses. SEH housing inventories are intentionally designed to protect affordability for not just the initial, but also subsequent, generations of households in the unit.

SEH programs proactively remove properties from the speculative market, establishing a durable supply of affordable housing units that (1) remains intact relative to market appreciation, even in the face of gentrification and (2) is sustained over time through nonprofit stewardship of properties.

SEH programs can provide access to wealth creation (often via homeownership). Unlike affordable rental programs, many SEH-based strategies focus on subsidizing affordable homeownership programs. For instance, CLTs enable lower-income households, who often are unable to achieve market-rate homeownership due to prohibitively high down payments and purchase prices, to attain homeownership. As the primary vehicle for wealth creation in the U.S., this stepping stone into homeownership becomes a critical asset for the household both now and in the future. In other cases, SEH programs seek to provide stabilized, affordable rents that enable households to redirect their incomes to other needs.

Three Key Characteristics of Shared Equity Models

Broadly, SEH models leverage two primary strategies aimed to generate affordable housing (Ehlenz and Taylor 2019). First, they deploy long-term subsidy retention strategies to embed affordable housing resources into their properties for the foreseeable future, ensuring the benefits (1) last beyond the first buyer (by linking the subsidy to the property itself, inhibiting the first homeowner from effectively becoming the sole beneficiary when they, subsequently, sell the home at market rate), and (2) extend past the lifespan of conventional affordable housing subsidies (e.g., LIHTC or Section 8 subsidies that are generally sustained for 15-30 years).

Second, they utilize resale formulas for owner-occupied properties, placing constraints upon the share of market-based appreciation a homeowner can realize upon resale of their home. In short, an SEH homeowner would expect to realize equity and modest appreciation gains when selling their home but would not recoup the full extent of market appreciation. This important feature enables the subsequent buyer to also benefit from below-market pricing. Based on the 2022 survey of US-based CLTs, approximately half of CLTs utilize an appraisal-based formula to determine resale price, with three-quarters of CLTs reporting that homeowners are eligible to claim 25 percent of market appreciation (Wang et al. 2023). Approximately one-third of CLTs rely on a fixed-rate formula and one-fifth use an indexed-based formula to determine resale prices and the homeowner’s share of appreciation.

Lastly, the principles of lasting affordability are typically enforced by ground leases, deed restrictions, or some combination of both (61 percent, 8 percent, and 17 percent, respectively; (Wang et al. 2023)).

CLTs are the most common form of SEH; other forms of SEH include limited-equity cooperatives and deed-restricted houses and condominiums, and resident-owned manufactured housing communities with permanent affordability covenants extending 30+ years (Davis 2017; NeighborWorks America 2021).

Spotlight on Community Land Trusts as a Primary Vehicle for Shared Equity Homeownership

CLTs offer specific strategies and, principally, homeownership-centered benefits. As nonprofit organizations, CLTs serve as a steward of long-lasting affordable housing supplies. The CLT removes housing from the speculative market by retaining ownership of the land, and thereby maintains affordability. Eligible homeowners can purchase the house and enter into a long-term land lease (or, less frequently, deed restriction) (Wang et al. 2023; NeighborWorks America 2021). The CLT embeds subsidies into the land, preserving the affordability for both initial and subsequent homeowners.

Meanwhile, homeowners engage with a resale formula to ensure they can both access modest appreciation benefits from ownership and preserve affordability for subsequent buyers. There are several critiques against this aspect of the model. Whereas a number of housing programs attempt to address either wealth creation (e.g., first-time homebuyer programs) or affordability (e.g., LIHTC), it is more difficult to strike a balance between both goals (Jacobus 2007). The limitations on resale equity are contentious, directly challenging the conventional benefits aligned with homeownership, with critics arguing resale formulas constrain wealth-creation for households who have already been most disenfranchised via wealth gaps (Lubell 2013; Jacobus and Sherriff 2009). SEH advocates respond by pointing to the enduring affordability of housing (representing a communal benefit), as well as the stewardship of the CLT that helps sustain homeownership for low-income households over time. For instance, one study found that more than 50 percent of low-income homeowners exit conventional ownership within five years—a period that is generally used as a minimum for recouping initial transaction costs (Reid 2004). In contrast, research suggests upwards of 90 percent of CLT households remained as homeowners after five years (Temkin, Theodos, and Price 2013). Additional studies underscore that CLT households generate more wealth than they would investing in, for instance, S&P 500 index funds. Champlain Housing Trust (Burlington, VT) found that CLT homeowners realized 25 percent appreciation in their investment over time (Jacobus and Davis 2010), while the Urban Institute estimated households earned returns between 6.5 percent and 60 percent on their initial investment (consisting of resale-restricted appreciation, principal equity, and down payment) (Temkin, Theodos, and Price 2010).

CLTs have been an effective strategy to offer homeownership to lower-income households. They rely on income-based eligibility restrictions, with nearly 60 percent of CLTs serving households at or below 80 percent of area median income (AMI) and an additional 35 percent engaging with households at or below 120 percent of AMI (Wang et al. 2023). Beyond income-based criteria, CLTs often require households to satisfy additional eligibility requirements, such as homebuyer education (91 percent), debt-to-income ratio (52 percent), asset limits (49 percent), first-time homebuyer status (40 percent), and down payment requirements (40 percent) (Wang et al. 2023). Collectively, these criteria are designed to broaden affordable housing access, targeting CLT opportunities towards households who are often unable to achieve homeownership in the conventional market.

Program evaluations and CLT scholarship generally underscore the durability of CLTs with respect to individual property performance. Emily Thaden’s assessment of SEH homeownership finds that SEH loans performed substantially better than conventional loans across several measures, including the number of homeowners facing serious delinquency (1.3 percent of SEH loans versus 8.6 percent of conventional loans) and number of loans in foreclosure proceedings (less than 1 percent of SEH loans versus nearly 5 percent of conventional) (2011). These findings are particularly revealing, since the SEH households—who were low-income, CLT-eligible families—were performing better than conventional loans as reported by the Mortgage Bankers Association’s National Delinquency Survey, inclusive of a full spectrum of incomes. A more recent program evaluation illustrates how SEH programs are successfully serving their intended audience: While SEH homebuyers are statistically different from conventional homebuyers (measured by lower credit scores, incomes, and revolving debt), their homeownership behaviors or successes are not statistically different from others (measured by rates of foreclosure and delinquency avoidance) (Theodos et al. 2017). Further, SEH homebuyers are not discernibly different from homeowners outside of SEH programs, with the exception that they retain smaller mortgages and have smaller monthly payments—supporting the affordable homeownership mission (Theodos et al. 2017). Scholars and CLTs primarily attribute these outcome-centered findings to the ongoing stewardship of the CLT via homebuyer education and ongoing support that aims to navigate potential financial struggles (Ehlenz and Taylor 2019).

Shared Equity as a Way Forward: Reassessing the Opportunity to Scale the Model and Address Growing Affordable Housing Challenges

Despite strong track records for providing durable affordable housing for lower-income households, SEH models face challenges related to their scale across several dimensions—the foremost being the small scale of the solution. Central challenges include:

- Challenges to Sector-level Scale for SEH Solutions: Even as SEH programs have grown, their contributions to the U.S. housing market remain extremely small. For example, while the LIHTC program includes approximately three million units, CLT inventories are much smaller with estimates of 40,000 units—approximately 1.5 percent of LIHTC supplies and roughly 0.03 percent of all housing units in the U.S. (143.8 million in 2022).

- Challenges to Organization-level Scale for SEH Programs: Directly linked to the overall scale of the SEH sector, organizational-level property inventories are typically small. For instance, among CLTs accounted for in the 2022 census report, Wang et. al. reported approximately one-quarter (28 percent) of CLTs owned between 1 and 20 units, roughly one-quarter (27 percent) had between 21 and 100 units, and approximately one-tenth had between 101-200 or 201-500 units (8 percent and 10 percent, respectively) (2023). Importantly, nearly one-quarter of all CLT respondents reported zero units in their inventory, primarily representing relatively young organizations established since 2019. In short, the start-up challenges are steep and property acquisition represents a durable obstacle.

- Challenges to Accessing Capital that Enable Inventory Growth: Property acquisition obstacles are a substantial driver behind the scale-related challenges for SEH. Specifically, SEH organizations do not have sufficient access to capital funding to enable them to acquire properties and expand their inventories—this is especially true in markets with steep speculative pressures.

Emergent Innovations in the Shared Equity Sector

As the SEH sector continues to wrestle with scale-based challenges, there are three emergent solutions that are in their pilot phases. While these programs rely on similar strategies—namely leveraging market-based rents and investor capital to help subsidize SEH (or SEH-like) units—they take slightly different approaches.

Capital Fund for (Future) SEH Acquisition

The first example represents a national approach to generating capital funding pools for future CLT inventories. Grounded Solutions Network (GSN) is establishing its first capital fund, Homes for the Future (Grounded Solutions Network 2023). The fund will provide the capital to purchase single-family homes in target markets, defined as possessing: (1) strong signals of upward housing market pressure (e.g., job and population growth, strong net in-migration), (2) existing SEH program partners, and (3) sufficient homes in communities of color that satisfy acquisition criteria. GSN has preliminarily identified 30-40 markets across the U.S. that could meet these criteria. As part of the strategy, the fund will be poised quickly to move in target neighborhoods ahead of speculative investors.

Once properties have been acquired, they will be rehabilitated as needed before being leased. The fund will partner with reputable property managers to rent its inventory at market rates for up to 10 years. During this time, the fund will hold, rent, and manage its housing stock as the units appreciate. Subsequently, the homes would be transferred to an SEH partner as part of a CLT portfolio. The cash flow from rentals would sustain the fund, while property appreciation subsidizes the purchase price for SEH homebuyers and provides principal and a modest equity return to investors.

The goal for the Homes for the Future launch is to secure 400+ homes from the speculative market, resulting in 360+ homes transferred into SEH programs as permanently affordable. The keys to success include scatter-site property management (at a sufficient scale within a target market) in the short-term, which will transition into scatter-site inventories for SEH programs in the future. GSN sees the opportunity to double the national production of SEH housing within the next decade.

Mixed Income Neighborhood Trusts (MINTs)

Trust Neighborhoods, a national nonprofit organization that brings together finance and public policy expertise to focus on affordable housing at the neighborhood level, launched the MINT model in 2020 (Trust Neighborhoods n.d.). The approach takes inspiration from the CLT model, seeking to preserve existing affordability in neighborhoods among rising rent levels.

A MINT operates as a land trust, locally managed by an existing neighborhood organization, that holds an inventory of scatter-site rental and retail properties. The goal is to acquire properties at a neighborhood scale, enabling access to different financing capital and generating a multi-property management strategy. The portfolio largely consists of naturally occurring affordable housing supplies, which are renovated and/or converted into new infill development. Subsequently, a minority of the portfolio is rented at market rents (which are typically rising with gentrification pressures). These rents generate sufficient subsidy to enable the remaining inventory to be stabilized at current rent-levels plus inflation. Lastly, any equity returns are split between funders and the neighborhood, which embodies a shared equity mission. Trust Neighborhood serves as an advisor and financial resources to the local MINT, providing underwriting, legal structuring, and access to financial capital (Bukiet 2023)

As of 2022, Trust Neighborhoods has supported two pilot MINTs—one in Tulsa, Okla. (12 properties) and another in Kansas City, Mo. (20 properties)—with several expressions of interest from across the country (Kemper 2022). The intent of the model is both to minimize displacement and shield an inventory of units from gentrifying pressures, as well as establish a financial model that supports the subsidized component of the portfolio in perpetuity. Presently, the MINT model is solely targeted at rental properties, so, unlike CLTs, it does not generate the opportunity for homeownership or wealth-building. However, it does provide a framework that could easily be applied to homeownership in the future.

Accelerating Community Investment (ACI): Solutions at the Confluence of Catalytic Capital, Public Finance & Community

The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy launched Accelerating Community Investment (ACI) in 2021, aiming to mobilize investment in low- and moderate income communities (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy 2023). The initiative connects public finance, impact investors, financial institutions and communities around new investment opportunities. ACI’s work has specifically focused on communities that have been excluded from access to mainstream financial and wealth-building resources. ACI has an initial three-year timeline, with the goal of establishing a network of leaders across sectors to build partnerships, receive training, and identify community-centered investment opportunities in community and economic development, housing, and beyond.

As a partner of the ACI, the Port of Greater Cincinnati Development Authority (the Port) is developing a strategy that leverages public finance tools in order to acquire homes from predatory institutional investors and return them to local control for resident-owned homeownership (Berlin 2023). While the Port’s approach does not exclusively rely on SEH models, it does engage public finance tools and mission-driven catalytic capital sources in a way that align well with SEH programs.

Through its own analysis and understanding of the local real estate market, the Port identified a startling trend for Cincinnati: Out-of-state institutional investors were purchasing single-family rental stock throughout the city, creating less than desirable neighborhood conditions and restricting housing supplies (either quality rental or affordable homeownership stock) for low- to moderate-income households. The Port’s key findings included:

Over 4,000 homes in the city were held by out-of-state institutional investors;

The rate of owner-occupied to rental conversions was increasing, accompanied by significant property deterioration;

Investor-owned properties were often owned by multiple LLC owners with some relationship to one another;

These properties were often subject to multiple ownership transitions within a portfolio, with a concentration among the most distressed properties; and

Investor-owned properties were often spatially concentrated in communities with more low- to moderate-incomes and/or residents of color.

Following their analysis, the Port had an opportunity to purchase nearly 200 homes from a multi-state institutional investor. The opportunity is in alignment with ACI goals and the Port’s solution offers a model for future investment. To secure the properties, the Port structured and created a bond-backed public finance structure that enabled them to secure over $16 million in an acquisition and initial capital repair pool. After purchasing the homes from the institutional investor, the Port held them via their land bank powers. Subsequently, they partnered with mission-aligned partners to facilitate property repairs and return them into the locally-owned rental market with a plan to transition the units into a low- to moderate-income homeownership pipeline.

The Road Ahead: Next Steps for Shared Equity Homeownership

Addressing the ongoing affordable housing challenges requires a comprehensive approach involving local, state, and federal levels. Innovative strategies are needed to overcome persistent market constraints, alongside a commitment to scaling successful models. SEH models offer a promising solution by increasing the supply of affordable housing and ensuring long-term sustainability through permanent affordability provisions. However, these models face significant obstacles related to scale and capital. To effectively tackle these challenges, policymakers and housing stakeholders must focus on expanding SEH through targeted policy tools, strategic land acquisition, and innovative funding mechanisms. By implementing these strategies, we can pave the way for more investment in equitable and resilient housing solutions that meet the diverse needs of communities across the U.S.

Developing strategies that respond to increasing demands for affordable housing is a national challenge. Housing shortages are impacting both large and small communities, shaped by a range of underlying real estate market, public policy and capital access strategies that can impede, prevent, and/or slow progress towards the production and preservation of housing across the affordability spectrum. The trend towards increasing housing cost burden remains troubling—not only from a housing access and fairness lens, but also more broadly due to the key role that housing plays in more equitably distributed economic growth and competitiveness.

Aurand, Andrew. 2022. “Improving Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Data for Preservation.” Washington, D.C.: National Low Income Housing Coalition and The Public and Affordable Housing Research Corporation. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/Improving-Low-Income-Housing-Tax-….

Aurand, Andrew, Dan Emmanuel, Keely Stater, Kelly Mcelwain, and Anna Ward. 2021. “Picture of Preservation 2021: A Joint Report by the Public and Affordable Housing and Research Corporation and the National Low Income Housing Coalition.” Washington, D.C.: The Public and Affordable Housing Research Corporation and the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Berlin, Loren. 2023. "A Bid for Affordability: Notes From An Ambitious Housing Experiment in Cincinnati." Land Lines Magazine. January 2023. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/bid-for-afford…

Bukiet, Louisa. 2023. “How 2021 Alum Trust Neighborhoods Preserves Affordability in Neighborhoods At-Risk of Gentrification.” Terner Housing Innovation Labs (blog). March 2, 2023. https://www.ternerlabs.org/post/trust-neighborhoods.

Caputo, David, Mary Le, and Matt Reidy. 2023. “Moody’s Analytics CRE | US Loses 8% of Affordable Housing Units During the Pandemic, Capital Investors Eye Entry into the Sector.” Moody’s Analytics CRE (blog). May 10, 2023. https://cre.moodysanalytics.com/insights/cre-news/us-loses-8-of-afforda….

Davis, John Emmeus. 2017. “Affordable for Good: Building Inclusive Communities through Homes That Last.” Shelter Report. Washington, D.C.: Habitat for Humanity.

Ehlenz, Meagan M., and Constance Taylor. 2019. “Shared Equity Homeownership in the United States: A Literature Review.” Journal of Planning Literature 34 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412218795142.

Freddie Mac. 2022. “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) at Risk.” Duty to Serve. Washington, D.C.: Freddie Mac. https://www.novoco.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/freddie-mac-liht….

Grounded Solutions Network. 2023. “Innovative Finance.” Grounded Solutions Network. 2023. https://groundedsolutions.org/how-we-do-it/innovative-finance.

Jacobus, Rick. 2007. “Shared Equity, Transformative Wealth.” Center for Housing Policy. http://www.nhc.org/media/documents/SEH_Transformative_Wealth2.pdf.

Jacobus, Rick, and John Emmeus Davis. 2010. “The Asset Building Potential of Shared Equity Home Ownership.” Working Paper. New America Foundation. http://affordableownership.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Shared_Equity….

Jacobus, Rick, and Ryan Sherriff. 2009. “Balancing Durable Affordability and Wealth Creation: Responding to Concerns about Shared Equity Homeownership.” Center for Housing Policy. http://www.nhc.org/media/documents/SharedEquityConvening.pdf.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. 2022a. “America’s Rental Housing 2022.” Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_….

———. 2022b. “The State of the Nation’s Housing 2022.”

Kemper, David. 2022. “Why Mixed-Income Neighborhood Trusts Can Help Build Wealth and Opportunity.” Where To Next (blog). May 3, 2022. https://wheretonext.org/2022/05/03/why-mixed-income-neighborhood-trusts….

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 2023. “Accelerating Community Investment (ACI).” Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/our-work/accelerating-community-investment-…

Lubell, Jeffrey. 2013. “Filling the Void between Homeownership and Rental Housing: A Case for Expanding the Use of Shared Equity Homeownership.” White paper HBTL-03. Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University. http://jchs.unix.fas.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/hbtl-03.p….

National Low Income Housing Coalition. 2023. “Out of Reach: The High Cost of Housing.” Washington, D.C.: National Low Income Housing Coalition. https://nlihc.org/oor.

NeighborWorks America. 2021. “Shared Equity and Cooperatively-Owned Housing: A Guide to Navigating the Models.” Washington, D.C.: NeighborWorks America. https://www.neighborworks.org/getattachment/57a35954-a321-4c7d-9042-a0f….

Reid, Carolina K. 2004. “Achieving the American Dream? A Longitudinal Analysis of the Homeownership Experiences.” Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology, University of Washington.

Temkin, Kenneth, Brett Theodos, and David Price. 2010. “Balancing Affordability and Opportunity: An Evaluation of Affordable Homeownership Programs with Long-Term Affordability Controls.” 23. The Urban Institute. http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/29291/412244-Balan….

———. 2013. “Sharing Equity with Future Generations: An Evaluation of Long-Term Affordable Homeownership Programs in the USA.” Housing Studies 28 (4): 553–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.759541.

Thaden, Emily. 2011. “Stable Home Ownership in a Turbulent Economy: Delinquencies and Foreclosure Remain Low in Community Land Trusts.” Working Paper. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. http://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/1936_1257_thade….

Theodos, Brett, Rob Pitingolo, Sierra Latham, Christina Stacy, Rebecca Daniels, and Breno Braga. 2017. “Affordable Homeownership: An Evaluation of Shared Equity Programs.” Research report. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. https://www.nationalservice.gov/sites/default/files/evidenceexchange/FR….

Trust Neighborhoods. n.d. “Trust Neighborhoods.” Trust Neighborhoods. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://trustneighborhoods.com/about-us.

Wang, Ruoniu (Vince), Celia Wandio, Amanda Bennett, Jason Spicer, Sophia Corugedo, and Emily Thaden. 2023. “The 2022 Census of Community Land Trusts and Shared Equity Entities in the United States: Prevalence, Practice and Impact.” Working Paper WP23RW1. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.